The idea of mutton leaves a bad taste for many US consumers—most of whom have never even tried it.

“Why can we only get lamb in the US, as opposed to mutton?”

That’s what Bobbie Kramer, a veterinarian near Portland, Oregon, was wondering when she responded to our recent call for reader questions about where their food comes from.

“As a meat eater, I enjoy the flavor and texture of lamb. But I’d love to try mutton. I know that in other parts of the world, lamb and mutton are more economical and popular to raise than cattle,” she writes. “I’ve traveled a fair bit (Australia, New Zealand, Europe and Great Britain) and have friends from parts of the world where small ruminants such as sheep and goats are raised for meat and fiber. My good friend from South Africa tells me how she and her husband miss cooking with mutton, which they find more flavorful and satisfying than lamb. What happens to the mutton-aged sheep here?”

It’s true that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to find mutton—defined as meat from a sheep over two years old—in American grocery stores. “Mutton is not an accessible protein option in the US,” says Megan Wortman, executive director of the American Lamb Board, an industry group aimed at expanding the market for domestic sheep products. If you’re looking to get your hands on some mutton, “you’d have to go through a specialty butcher shop or directly to a special-order processor,” she says.

Mutton has less tender flesh and a stronger flavor than lamb, which comes from sheep that are less than a year old. (Meat from sheep aged one to two years is generally called “yearling” in the US, and “hogget” elsewhere around the world.) That stronger flavor lends itself to curries, stews and “value-added” products such as spiced sausages, says Wortman, “so most of our mutton goes into value-added products or into specialty ethnic markets at this point.”

Some mutton is exported to Mexico, where it’s braised low and slow, barbacoa-style. Mutton is also often sold at butcher shops that serve communities that have brought a taste for the meat with them from elsewhere, such as new immigrants from Africa, Central America and the Middle East. (Wortman notes that the majority of US lamb and mutton is halal processed.) And in western Kentucky, a tradition of barbecued mutton still holds, although no one is quite sure why.

“There are consumer segments that would raise their hand and say ‘yes, I would prefer a stronger flavor,’ but we just don’t market it in mainstream grocery stories,” says Wortman. “There’s definitely a general hesitation that the minute you label it ‘mutton’ the average consumer has negative connotations with that product.”

So, how did mutton, a widely consumed protein around the world, come to be unmarketable to most Americans?

Sheep were first brought to the southwestern US by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, and flocks grew with the influx of European settlers, who utilized sheep locally for their wool and meat. With rising demand for wool in the 19th century, sheep farming became more industrialized, but the primary focus was on the wool, not the meat. Simply put, mutton was a byproduct of wool production.

Mutton was slaughtered, sold and canned locally, but no large-scale infrastructure arose to source and process sheep meat. “The simplest story is that no commercial meat industry developed around mutton,” says Roger Horowitz, a historian and author of Putting Meat on the American Table. “It seems to me that it was very rural in character.” He points to a can of roast mutton in his collection, dating from the 1890s, as emblematic of the time: It advertised that its contents were both slaughtered and canned “on the range” in Fort McKavett, Texas.

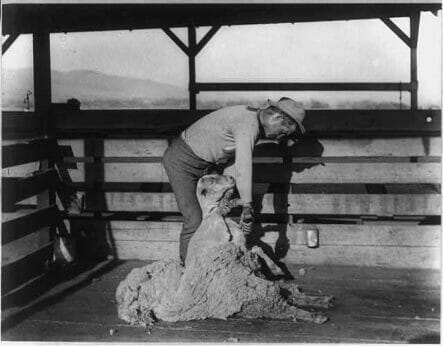

A man shearing a sheep at the San Emigdio Ranch in Kern County, CA in 1890. (Carleton E. Watkins/Library of Congress)

That’s not to say that mutton wasn’t consumed at the dinner table. Mutton chops were featured in cookbooks and restaurant menus from the late 19th and early 20th century, as the population grew and urbanized and demand for protein rose. Lamb was a seasonal product served at Christmas, and for a time, sheep meat was seen as a food for the upper classes. Even first-class passengers on the RMS Titanic were served grilled mutton—for luncheon and breakfast.

Sheep numbers in the US peaked in 1884 at 51 million head. But with the advent of synthetic fibers in the 20th century, wool production began to flag, and sheep numbers—and the availability of mutton—declined. (In 2016, there were five million head of sheep in the US.) Lamb consumption began to dwindle, too: Americans consumed five pounds of lamb per person in 1912. Today, that number is about a pound per person annually.

Pork, Horowitz notes, was more convenient. “Everybody had pigs, and pigs are a lot better to raise for meat because they eat anything.” And when it came to grazing animals, cows just made more sense: They provide far more meat per animal, and demand for beef was—and remains—high.

This woman does not want to cook mutton. (Photo: Ethan/Flickr)

By the end of World War II, mutton had come to symbolize everything that Americans wanted to leave behind. Men returned from the war swearing they’d never eat another bite of mutton after stomaching tinned army rations that included the notoriously unappetizing “Mutton Stew with Vegetables.” Women were enjoying new appliances that allowed them a modicum of freedom from household chores. Modernity and convenience were all the rage, and mutton, which requires dry aging and long, slow cooking times to become tender, was neither modern nor convenient. If mutton ever really had a heyday, by midcentury, it was over.

“I joke sometimes that I do lamb by day and sheep by night,” says Cody Heimke, who, in addition to managing the Niman Ranch lamb program, raises a heritage breed of Shropshire sheep on his property in south central Wisconsin. The flock of about 50 head are raised primarily for breeding, but Shropshires were at one time the most popular sheep in the world, primarily because of the quality of their mutton. “[The] breed of sheep doesn’t really matter when it comes to the flavor of lamb, but it does when it comes to the taste of mutton,” he says.

Heimke does “a little bit” of direct lamb and mutton sales when he has sheep to harvest, selling middle cuts to a restaurant in Madison, and utilizing the rest for sausages in varieties such as Bavarian-style, Merguez and spicy Berbere. He acknowledges that there isn’t a lot of demand for mutton. “I got a call this year, somebody looking for mutton, which is rare. I don’t usually get those calls.”

His advice for would-be mutton eaters? “Find somebody at a local farmers market that’s selling lamb. You really gotta find somebody that’s raising sheep and doing direct marketing, and ask them if they’re doing any mutton.”

For his part, Heimke says he enjoys mutton in sausage form. Last year, one of his wholesale clients was looking for ground lamb, but he didn’t have any in stock. “I’m like, ‘Well, what about ground mutton?’ And we [sold] one-pounders of ground mutton,” he says. “I tasted that before I sold any of it, and it was as good or better than any ground lamb I’ve ever had.”

Have you ever eaten mutton? Do you want to try mutton—or not? Tell us what you think in the comments below.

Thanks to Bobbie Kramer for submitting her question for our “Digging In” series. Got a question about where your food comes from? Let us know what you’d like us to investigate next by filling out this form.

Mutton is common in western Kentucky.

My butcher once told me that in NY the law said he can sell lamb or mutton, but not both in the same shop, the reason being that you might substitute mutton for more expensive lamb (or was it the opposite?) I often see mutton on Indian and Pakistani menus, but I assume it’s just lamb. Those curries are so highly spiced it would be hard to tell the difference

Mexican barbacoa, made with mutton, is one of my favorite meals. Incredible. In Scotland they take sheep VERY seriously. At the big farmer’s market in Edinburgh, they sell lamb, hogget, and mutton. My favorite is hogget, which is sheep older than lamb and younger than mutton. In other words, between one and two years old.

We’re eating ground mutton every month here in Maine; sold at a local organic farm, which also sells different cuts of lamb. Can’t beat a mutton ragu with pappardelle noodles, especially into the colder months.

Having raised sheep, a big issue with American palates is that for some reason they are allergic to flavor and older wool sheep definitely have more funk in the flavor department however hair sheep are much more mild in flavor due to the lack of lanolin so a hair mutton is going to be the same level of funky flavor as a wool lamb i.e. not as much. The flavor really depends on the cut as well, mutton chops are amazingly good to my taste and are superior to lamb chops. Mutton leg has a stronger flavor and is more… Read more »

One of the biggest problems with sheep and other meat-producing-livestock here in New Mexico is the lack of slaughter-houses. If I understand correctly sheep have to be transported to California for slaughter – which is a thousand mile journey.

I was raised between France and N Africa and mutton was preferred over lamb except for grilled dishes

I have fond memories of mutton liver and lamb kidneys grilled on a skewer

I am opening a field to fork event space at our 15th st urban farm in St Petersburg FL

We shall be serving mutton dishes and intend to show guests what they have been missing

In India lamb and mutton are often same for consumers. Second one is more preferred.

I bought a lamb early this year from a livestock owner that also raises various fowl, goats and heritage pigs

I Have considered contacting her about mutton, since the lamb was only 35 pounds (vs the 1K pound steer also in my freezers) and I imagine that a bigger animal would also taste as good. My cooking Forte is slow cooking anyway. Thanks for the article to remind me to order a sheep next time.

Very good article!

Perhaps if mutton were to be promoted for it’s health benefits, people might consider changing their meat choice? We mutton lovers can only hope!