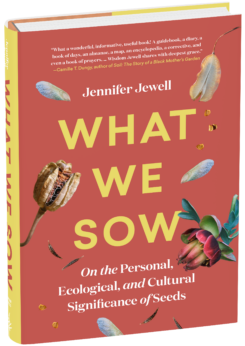

Our culture is stunningly “seed stupid.” Here’s why we should understand how seeds work, what’s at stake and who is doing the work to preserve and protect this all-important resource, excerpted from What We Sow, a new book by Jennifer Jewell.

In mid-March 2020, California became the first state to order its nearly 40 million residents to stay home and all nonessential in-person businesses to close down in an effort to stop the spread of COVID-19. Cases of the novel coronavirus had been in the news, at first sparingly and then ever more urgently, from January to that moment in March, so the crisis response was not a surprise, but the halting of life as we knew it was as novel as the virus.

My partner, John, and I were traveling in the early days of a long-planned speaking tour as the concern and confusion regarding the crisis reached its first fevered pitch. Tour events disappeared in front of us wholesale. But my first thought upon hearing about the California lockdown orders was not “How do we get home?” or “How do we keep from getting sick?” or “How do I stem the ebbing of my work and income?” As gardeners, our first thought was “We need to order seeds.”

We were not, apparently, the only gardeners to have this instinctive thought. When I got online the day after the lockdown orders, before being able to get on a flight home, “Out of Stock” and “Back-ordered” popped up on our computer screens over and over again from our favorite organic seed sellers: Redwood Seeds, Peaceful Valley Seed, Territorial Seed, Fedco Seeds, Hudson Valley Seed, Seed Savers Exchange, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, Kitazawa Seed, Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. As a gardener, to feel a sense of scarcity in the seed supply was an alarm bell ringing—and ringing loudly in my mammalian brain, triggering survival anxieties and a determined instinct to engage with my own survival. Our collective survival.

As gardeners, our first thought was “We need to order seeds.”

Seed is important: Botanists know this, ecologists know this, farmers and horticulturists know this and most gardeners have a pretty good basic understanding.

But, if many of our (human) species are overwhelmingly “plant blind,” even more of us are stunningly seed stupid—many of us are not sure exactly how they work, how they’ve evolved, how they are being handled at legislative, commercial or, perhaps most importantly, cultural levels, and why this matters.

Jennifer Jewell.

In the midst of climate crisis, a precipitous rate of biodiversity loss in our world, a global pandemic, attendant financial chaos, global social-justice reckoning and now the most globally reverberating war in the last 50-plus years, we as humans, and in the United States as an industrialized society, are being offered an intense short course in what we need most in this world, what is in fact essential to our lives: Community, family, health, dignity, clean water, clean air, access to some open space and sufficient food are all unquestionably on this list of essentials. Foundational to clean water, clean air, and sufficient food are … plants.

Foundational to the vast majority of plants on our planet are their seeds: the smallest form of, the very essence of, these plants.

In this bizarre moment of colliding urgencies for life as we have known it, we are collectively being offered an opportunity to remember and really understand the essential importance and power of seed in our world: for food, for medicine, for utility, for the vast interconnected web we include in the concept of biodiversity and planetary health, for beauty and for culture, whatever that might mean to us.

This recognition of the importance of seed on micro and macro levels did not just happen in March of 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic in full form, with increasing climate extremes of the last several years or with the Russian invasion of Ukraine disrupting geopolitical stability and global food security and health. On the contrary, the stewards of the “seed world,” that dedicated sector of our independent plant-engaged world, have been sounding the alarm and preparing the soil for a likewise global seed-literacy and seed-protection revolution of sorts for many years.

The seed world is rich with scientists, spiritualists, growers, activists and protestors who have been keeping seed alive, accessible, shared and safe. These seed stewards have been preparing for the battle ahead as seed (its integrity, its diversity and our open access to it) has become increasingly threatened. These seed keepers have been declaring loudly to all who would listen why we should join in the work to know and care for seeds ourselves as one of the most proactive steps we can take to rebuilding our human food systems, our social systems and the global ecosystems of biodiversity on which we all depend.

Since the 1980s, when the first GMO seed patent was issued, and the 1990s, when reporting began in earnest about seed supply strategically (and stealthily) being consolidated into the holdings of large agribusiness-chemical corporations, the smaller seed sowers, growers, banks and knowers have been recording and responding. Their strategic, heartfelt, ground-level actions—documenting, saving, sharing and protecting seed—protect us all.

Excerpted with permission from What We Sow: On the Personal, Ecological, and Cultural Significance of Seeds (Timber Press, 2023)

The Author is correct, let us look on the bright side there are thankfully many people who are active in preserving open pollinated seeds. It will be a long struggle against Goliath. For all creatures great & small bring all into the light. Bravo for this expose, let’s all be active.

Detroit has embraced the idea of urban farming.I wonder how many other cities have done the same.