In her new book, Francine McCabe explores what it means to be part of your “fibershed” and what’s standing in the way of a local and sustainable fiber economy.

Look inside your closet—do you know where your clothes come from? Could you identify what materials they are made out of? How long would it take them to break down, once you’re done wearing them?

Before the late 1970s, around 70 percent of the clothing that Americans bought was made in the country. As the world became increasingly globalized, this changed. Much of America’s clothing production was moved overseas. Today, most of the wool used in clothing comes from Australia. Synthetic fibers made from raw substances such as petroleum also extended the distance between local economies and natural fibers by offering a cheaper and faster alternative. Today, “fast fashion” results in far-reaching environmental and social impacts, such as exploited cheap labor and the use of harmful dyes and unsustainable fibers. What do we lose when we are removed from our fiber sources?

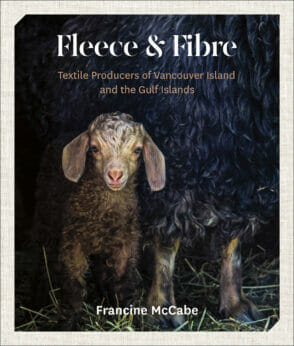

Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in British Columbia, Canada, have many artisanal textile farms. In her new book, Fleece & Fibre: Textile Producers of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, Francine McCabe takes you to them. Through thoughtful accounts of farm visits and original photos of charismatic animals, McCabe guides readers through the materials that are made in her region, as well as the farmers, plants and animals that produce them.

Beyond the individual farms, McCabe also paints a larger portrait of the textile landscape in Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. The area seemingly no longer has any processing mills for raw fibers. As a result, much of the material produced in the region has to leave to be processed, and it can’t be sourced by makers or artisans looking for local product.

In this book, which comes out October 10, McCabe digs into what it means to have a local and sustainable fiber economy and explores the confluence of industry and art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Modern Farmer: You begin the book with a quote from Indigenous writer and bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer: “To love a place is not enough. We must find ways to heal it.” Why did you choose this quote and how is this sentiment reflected in your book?

Francine McCabe: Everything she writes is wonderful and touches my heart. I read [that quote] while I was in the very early stages of researching for this book. And I just felt like that was the sentiment I wanted in this book. That was the through-line I wanted this book to have. I love Vancouver Island and I love the fiber economy we have here, and I would love to see it grow and be nurtured and for consumers to be more aware of what is going on in our fiber economy around us—and the importance of our textiles as a place-based symbol of where we come from.

Our textiles are gorgeous, that come from here. And it can be a way to showcase our beautiful land and our place. When I read that quote, it really spoke to me because I feel like if we can grow our fiber economy and we can nurture our textiles here, that is a way of us nurturing our land and taking care of the place we live.

Bluefaced Leicester X at New Wave Fibre. (Photography by Francine McCabe for Fleece & Fibre)

MF: You use a concept term in your book that might be new to many readers. What is a “fibershed”?

FM: I haven’t coined this term. It is from Rebecca Burgess, who is from California; she is the founder of the fibershed concept. But fibershed, technically, it’s the same as a watershed. It’s the place where you can get your raw materials, you can process those raw materials with transparency, in a specific way that is specific to that land, to that place. Each little pocket, each fibershed through our country, can produce the same breed of fiber, but it’s going to be different. It’s going to be processed differently, the feeling’s going to be different. So, a fibershed encompasses our raw materials, our makers [and] what’s specific to this region.

MF: The Coast Salish history of fiber work, before sheep were introduced to the area, was based on now-extinct Woolly dogs, mountain goats and many types of plant fiber. How can knowing the history of the fibershed inform the decisions we make as consumers?

FM: It was really neat to read a lot of that history because I had seen that there was a lot of fiber in our region that is no longer used because it wasn’t properly utilized. The processes of making it weren’t supported. So, now I see how much fiber we have here, and I want those fibers to be supported and utilized so that they don’t disappear. So, just to talk to some people about the Woolly dog and how much it was utilized and how it was the main fiber here and now it’s basically extinct…It’s pretty sad to hear. You don’t want those fibers that are specific to our region to disappear any further. So, I think that was really important to hear those stories and to really solidify the importance of processing our fiber locally, as much as we possibly can, using it, showcasing it.

Francine McCabe, author, “is a mixed-blood Anishinaabe writer, fibre artist, and organic master gardener from Batchewana First Nation, living on the unceded traditional territory of the Stz’uminus First Nation with her partner and two sons.” (Photo courtesy of Francine McCabe)

MF: You highlight an interesting discrepancy in your book between the amount of financial support and grants available for food-based agriculture and the lesser support for fiber-related farms. Why do you think this disparity exists?

FM: I think it’s maybe because all of our textile production has been moved overseas—out of sight, out of mind. So, people aren’t questioning it as much. The idea of transparency in our textiles hasn’t been brought [to] our attention as much as it has with food, even though food and fiber are both agricultural issues, they both start from the land and our dependence on the land and farmers. But I think that people just aren’t quite aware of it as much or we don’t consider it as much. Clothing and textiles are something we’ve kind of taken for granted as part of our surroundings, but they are just as impactful as our food that we are taking into our bodies.

MF: You set out to answer a pretty specific question—why is local fiber so costly to produce? You found your answer: no local mills. How would introducing more local infrastructure change the textile industry in Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands?

FM: There are people here who are interested in starting that, but the startup is extremely expensive. And there’s no government funding at this time, that’s like, ‘here’s the startup for a fiber-related business.’ So, a lot of people are struggling with just how to get funds to start that.

But if they were able to start that, every single farmer that I spoke to in this book said they would use a local fiber mill, if it was here. So, if there was somebody who had extra funds to start a fiber mill, they would be in business, and they would have years worth of fiber to process. If I had the money, I’d be all over that. And it would change our infrastructure because it would allow for a lot more of our fiber to be processed right here on the island, which would bring down the price for farmers. It opens up a bunch of different doors and a bunch of avenues for local businesses. It would be a huge boost for the economy.

Fleece from Gotland sheep. (Photography by Francine McCabe)

MF: You advocate that consumers demand the same transparency from our textiles as our food—we need to know what is in our textiles. What are some of the issues woven into mass-produced textiles?

FM: A lot of products that you buy that claim to be 100 percent natural [or] organic, the material may have been grown organically and the material itself might be 100 percent cotton, but then it’s finished with a finishing product that leaves a residue on the fiber that would never allow that fiber to break back down into the soil. So, yes, the fiber itself is natural and organic, but the chemicals in the process that they’re using to dye it and to treat it is not organic.

It’s one of those confusing things, as it is with food. Like “organic”—what does that really mean anymore? And so with our clothing, it’s the same thing. They say things on them, like “ethically sourced,” but what does what do those words really mean? For us as consumers to just demand from our brands, what does that mean? What does ethically sourced mean for you? And who’s making your products? Where’s the material coming from? Just more questions we could be putting onto the brands so that they feel the need to have more transparency.

Yarn being dyed at Hinterland Yarn. (Photography by Francine McCabe for Fleece & Fibre)

MF: In reporting for this book, you visited several different farms, spoke with a lot of innovative people and met many photogenic animals. I’m sure they all stand out in their own unique ways. What specific highlights or takeaways will stick with you?

FM: I got to meet the Valais Blacknose breed [of sheep], which was one of the breeds I really wanted to meet. And they were just as cute as I expected them to be, and friendly, so that was great. But I think really just being able to see the farmers and see their actual passion for the fiber solidified that this book was where I really wanted to go, because I wanted to help them pass their message along and wanted to connect them to other makers.

MF: You encourage readers to stay “fiber curious.” What does that mean to you?

FM: When you go to purchase products, maybe look at your tag, see what they say, just look for local stuff. If you’re thinking you want a new sweater, maybe get curious who’s making sweaters in your 15-mile radius around you and see if those are the types of sweaters you might want, versus going out to the store to buy one. Just stay curious about what is happening with your textiles [and] where they’re coming from. Think about them as you would your food.

We are at a time in this world where it’s important to consider all of these different avenues, not just our food. And maybe it’s time to change how we produce and consume our textiles, as well. I think it’s just important that people realize that our textiles are an agricultural product. We are depending on farmers and the land for these things, as much as we are our food.