In Koshersoul, the author and food scholar embraces his Judaism by interweaving it with the Black cooking traditions of his ancestors.

For author, chef and food historian Michael Twitty, food is the great equalizer. Food tells a story of the people who made it and all of the people who came before them. It’s a necessity, it brings pleasure and it ties us to our ancestors.

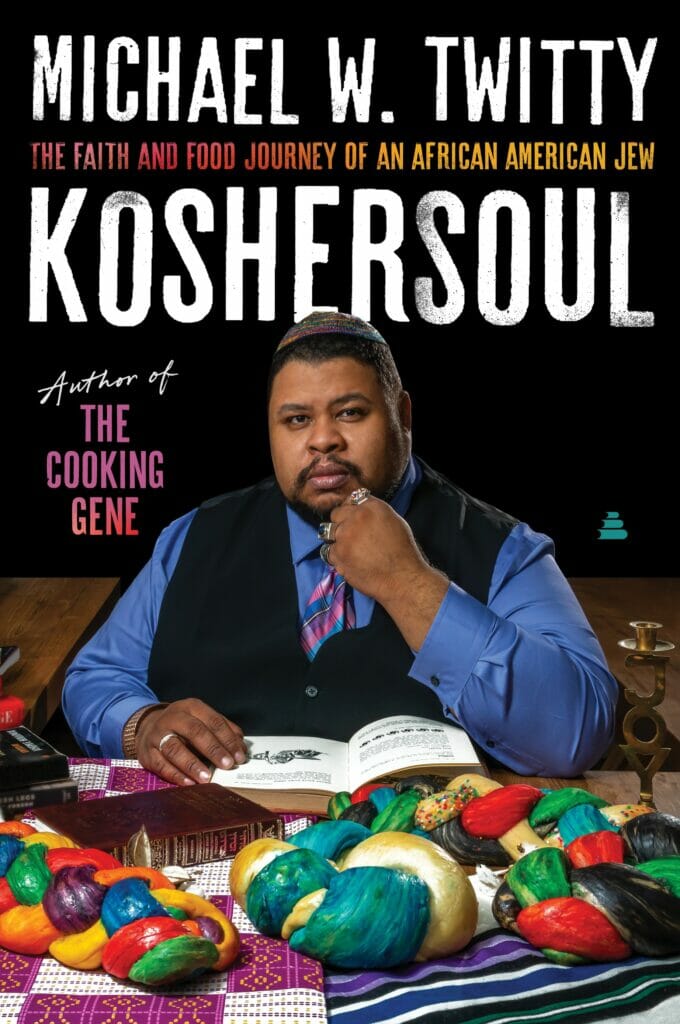

Twitty first offered an illuminating look at the intersection of African American culture and cuisine in his James Beard Award-winning memoir The Cooking Gene. Now he’s back with a new book, Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew, in which he interrogates his own connection to Judaism and Jewish food. With both recipes and personal stories, Twitty introduces the reader to traditionally Jewish foods, with a soul food-inspired twist.

As someone who is both Black and Jewish, Twitty makes the deliberate choice to be public and loud about every aspect of his identity, to reinforce his own belonging in both communities. “I belong as a Black man, I belong as a gay man, I belong as a Jewish person, I belong as a Southerner. I belong as all of those things,” says Twitty. “We live in a time when wearing a yarmulke outside can be confrontational. But we also live in a time where people have tried to fall into these immutable identities and forget about the flow, forgetting that we all bleed into each other. Nobody is not intersectional.”

For Twitty, existing in all of his facets is both a quiet revolution and a totally mundane exercise—at least it is now. Twitty converted to Judaism when he was 25, and he remembers attending Howard University (an historically Black college and university), while taking classes in Jewish studies at American University, where he noticed changes in atmosphere between each classroom. At American, the classes Twitty took in Jewish Studies were often conversational, where students were encouraged to debate. At Howard, however, Twitty says the classes were more structured and traditional, and speaking out of turn was seen as rude. At first, he learned to adapt to both environments, code-switching as needed. But he began to bristle at the very idea that a community’s natural way of speaking might be perceived as rude by outsiders. “There are multiple ways of being rude in the same way,” Twitty explains. “So, we have to really understand each other. Having those conversations matters.”

Now, rather than switch between his identities, he embraces them all and challenges others to do so as well. The first step, as always for Twitty, is with food. In Koshersoul, he dives deep into the similarities between Jewish food and soul food.

Both communities have made use of ingredients that others have discarded or seen as less desirable—cooking with offcuts of meat, using lard and taking time to make things such as chitlins, buckwheat groats and herring. “Herring to me is like what salt pork was to my Southern ancestors. It’s a salty, umami thing that went in everything,” Twitty says with a laugh. And while many folks might associate soul food with pork, Twitty says smoked turkey is a much more common ingredient—meaning that configuring soul food to work within the rigid structure of kashrut, keeping things kosher, was easier than it might seem.

There are many rules to ensure food remains kosher, but the big ones are that meat and dairy never appear in the same meal, and there is no pork or shellfish allowed. While most of the classic southern recipes adapted easily, Twitty says the loss of shellfish was the hardest to work around. “The shellfish thing can be tricky. I really wanted to do some recipes in the book that were more gumbo-ish, that utilize kosher shrimp. But those are iffy and touchy. [I figured that] people could do that on their own if they wanted to.” But even without a gumbo, Twitty’s recipe adaptations feature classics such as a macaroni and cheese kugel, a collard greens lasagna and a matzo meal fried chicken. He even puts together suggested menus for everything from Shabbat to Juneteenth celebrations.

Both the Black and Jewish communities also have large, diasporic populations, spread out far and wide. One of the best ways to see the connections people have as they disperse across the globe, Twitty says, is through their food. “Anyone who looks at Afro-Mexican cuisine can clearly see some links, and it goes on to Afro-Brazillian, Haitian food. And then back in Black American foodways, we have what happens in the Chesapeake, the low country, Florida, Gulf Coast, Louisiana, the cotton belt of Texas and beyond.”

Similarly, Jewish food has adapted as it’s moved around the world, picking up influences from a multitude of European and African influences. Even so, both cuisines are often reduced to one or two dishes that aren’t that representative of the diet as a whole. “For example, everyone likes brisket. OK, but you’re talking about a food that some people only got to eat about once a year,” says Twitty. “That’s emphasizing the foods that are in an American, or British diet, where meat is king. But that’s not what would have been prominent.”

For this reason, Twitty also includes a blueprint for several gardens in the book as well; the Ashkenazi garden, the Sephardi garden, and the African American garden. The garden blueprints list ingredients and crops common to different cooking styles and also encourages people to get back to growing some of their own food—something that many Jews and Black folks have consciously moved away from, through social movements such as the Great Migration.

Twitty, instead, invites them back to the garden. “You can cultivate and grow and learn and delay gratification and focus on your diet and things coming out of the ground,” says Twitty. But it’s also more than just growing your own cucumbers. It’s about challenging stereotypes. “There’s [the idea that] Jews look like this, and Jews don’t look like that. All those things are part of Jewish survival and peoplehood. And you know, it’s not trivial. It’s not just a choice. It’s a real question we have to confront.”

In the book, Twitty describes Jewish food as both “born in a challenge” and as a “recovery food.” These might seem like opposing forces, but they’re not. Instead, he likens the ideas to a call and response. One naturally follows the other. In Koshersoul, Twitty asks the reader to spend time with the idea that food is much more than sustenance. Instead, food joins communities in unexpected, and often delightful, ways.

It is an incredible book and definitely had me exploring my identity further through food. I am sharing this book page for anyone who wants to see his tour stops http://www.koshersoulbook.com