This year, birds are smaller, more expensive and in short supply.

Americans won’t have trouble finding a Thanksgiving turkey, but they may wonder if this season’s hens were put on a diet, based on the supply of smaller-sized birds with inflated price tags.

However, experts say that avian influenza outbreaks and steep operational costs throughout the supply chain are to blame for the smaller-than-average birds.

Ashley Klaphake, a third-generation turkey farmer based in Melrose, MN, has certainly felt the pressures of inflation. Feed is roughly 20 percent more expensive compared to last year and anything that requires gas or propane, such as heating her barn, has shot up by 10 to 15 percent.

“It’s really been a challenging year for the sector,” she says. “Just when you think you’re caught up and have made it out of the last two years of…the pandemic, prices spike and the bird flu hits.”

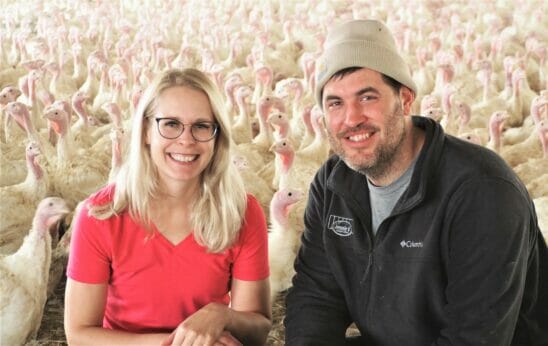

Ashley and Jon Klaphake with their turkeys.

Since March, more than 7.4 million commercial market turkeys have been euthanized due to avian flu outbreaks. This is a loss equivalent to roughly five percent of annual U.S. turkey production. Minnesota, the country’s top turkey-producing state, has had the most commercial poultry flocks affected by the virus. As of mid-November, the state has had 78 cases with more than 3.8 millions birds euthanized.

Avian influenza, a highly contagious virus, comes from wild waterfowl, such as ducks and geese. When domesticated poultry, such as chickens and turkeys, comes in direct or indirect contact with the feces of infected wild birds, they become infected and start to show symptoms, such as lethargy, coughing and sneezing and often sudden death. To stop the spread of this highly contagious virus, producers resort to culling.

Klaphake, who raises roughly 345,000 turkeys each year, has so far managed to shield her flocks from avian flu. But she fears for the day when that’s no longer the case. Recently, outbreaks in her region have been reported and she’s aware of neighbors who’ve been directly impacted.

Farmers with flocks that become infected must complete a carcass disposal, followed by thorough cleaning, disinfecting and a 28-day down time period where they are unable to start raising flocks. The state also has to complete three rounds of surveillance testing on birds before they’re cleared to enter commercial markets. The entire process can push producers back by 10-15 weeks, Klaphake says, but she’s heard of farms that have been behind by three months because it takes so long to get state approval.

Producers are also eligible for federal indemnity payments. These cover costs associated with animals that have to be destroyed because of avian influenza as well as culling, cleaning and disinfecting. The catch, however, is that financial assistance often doesn’t cover all of farmers’ expenses.

To play catch-up, Michael Stepien, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, says farmers are increasing the production of lighter-weight birds they can raise in a shorter amount of time.

“In September, there was a 4-percent shift in traditional production patterns from heavier toms to lighter hens,” Stepien says. “By processing lighter birds that have a shorter grow-out cycle, the industry can increase the number of whole birds for the holiday season.”

Still, the USDA’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report forecasts turkey meat production for the fourth quarter of 2022 at 1.290 billion pounds, a decline of 5.6 percent from 2021. The latest data from the Consumer Price Index shows that turkeys are roughly 17 percent more than expensive than they were in 2021.

David Ortega, a food economist and associate professor at Michigan State University, says the reason why farmers, such as Klaphake, are seeing their on-farm expenses soar has a lot to do with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is exacerbating grain, fertilizer and energy prices.

“Cost of fertilizer and cost of grain has gone up and that goes into the cost of feed,” he says. “Naturally, this means birds will be more expensive to raise. Fuel diesel, needed to transport birds across the country, that’s spiked, too.”

Labor shortages throughout all segments of the food supply chain also play into higher turkey prices, says Ortega. There may also be increased demand this year, as more families are planning to gather together now.

Regardless, Klaphake says she hopes that Americans understand that it’s not farmers’ intent to leave anyone feeling squeezed when they reach the checkout line.

“It’s a lot of work to put food on the table and get turkeys to market,” she says. “Any business, any person, is affected by inflation right now. Farmers aren’t the exception… I think that’s why this holiday season is so important for us and our bottom line.”

Thanks for sharing this!