A new book offers an overlooked perspective of Indigenous knowledge and the role it can play in the face of climate change.

The past year has seen record-breaking heat waves, towns swallowed by floods and droughts that have drained water reservoirs dry. But amid voices in mainstream science warning of rising global temperatures that will only make conditions worse, some are calling for the need to legitimize Indigenous knowledge in order to pave a better path forward for the planet.

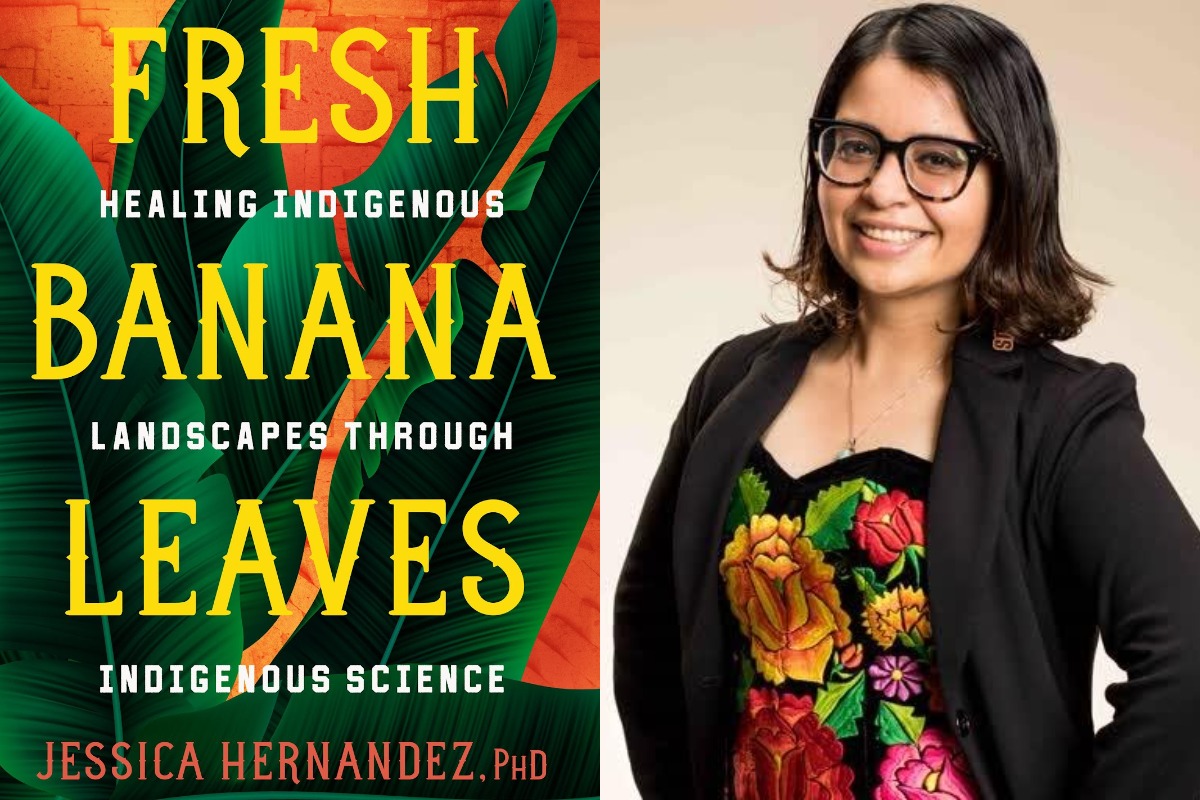

In her new book, Fresh Banana Leaves, Maya Ch’orti’ and Zapotec Indigenous environmental scientist Jessica Hernandez attempts to broaden the narrative around environmental destruction, pointing to why western methods of conservation will not be sufficient in the face of climate change. Using a number of Latin America-based case studies, personal anecdotes and history, Hernandez draws on the resilience and efficacy of Indigenous knowledge in land management practices that have stood the test of time.

At the heart of her account, however, is the banana leaf. To Hernandez, it is a symbol of Indigenous kinsentric ecology, a worldview where humans are closely related to other natural entities. It is the reason why her father survived the Central American Civil War and it is the source of understanding herself as an Indigenous woman displaced from her ancestral lands.

In advance of her book’s release today, Hernandez spoke with Modern Farmer about how viewing climate change through an Indigenous lens can inspire people to take meaningful action, what that action looks like and why farming systems engineered by her ancestors give her hope for the future.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Modern Farmer: Was there a specific experience that inspired you to write this book?

Jessica Hernandez: As a child, I never understood the full depth of war and what my father might have experienced as a child soldier during the Central American Civil War. But as I started going into college, taking courses on Indigenous studies and Indigenous history, I became more aware of this being something important to tap into. My father, he’s getting older and he’s an elder. Throughout my undergraduate degree, I realized the importance of storytelling and preserving our elders’ stories.

When I wrote the manuscript for this book, I wanted to do it in a way where I could write about my father’s story so that it could be preserved for future generations, but do so in a way that would tie it to the environmental sciences from an Indigenous lens because it’s not a perspective widely recognized in western science.

MF: In the book, you use permaculture as an example of a white person inappropriately capitalizing on Indigenous knowledge. Moving forward, how do people who are non-Indigenous to the land they inhabit become part of effective land management practices that still honor or are inclusive of Indigenous knowledge?

JH: Often, it comes down to learning the history and learning the history of the land you are on. For example, lots of people are unaware of how permaculture became a field. Even learning the history behind conservation because it did a lot of harm toward Indigenous peoples. National Parks, for instance, have displaced many Indigenous communities across the Americas.

In the book, I provide case studies of what happened to my father’s lands being converted into national parks because they are beautiful spaces…There also needs to be an effort in uplifting Indigenous voices, making an effort to understand how individually we can do that, but also calling out what is wrong when we see it. Oftentimes, Indigenous people are treated as research subjects rather than being the experts or even provided the opportunity to become the researchers.

[RELATED: New Indigenous Food Lab Looks to Mend a Broken System]

MF: In 2021, you were hired as University of Washington’s first Indigenous faculty member to teach a course on climate change, two years after the school introduced its Indigenous studies program. You note that academia lags on integrating Indigenous knowledge into science, but if we see these perspectives more widely integrated, how do you think it could change the way we look at the environment?

JH: Science continues to portray this person of a scientist typically being a white, cis-gender male. You don’t see other identities or perspectives represented very much and this can cause people outside of that persona to become skeptical of science and wonder who it benefits.

Integrating other knowledge systems is about seeing the bigger picture of solving climate change, and if we offer additional voices in the narrative, I think we will see less skepticism and more acceptance around science. If we are able to amplify the stories and hear about people already being impacted, like Indigenous peoples, I think more people will understand the ways of healing our lands and care about doing something. We are starting to see what happens when some of these conversations take place, with President Biden issuing a memorandum that recognized Indigenous science. But I feel the next generation will be responsible for a larger shift taking place in environmental policy.

[RELATED: The Seed Saving Descendants]

MF: In the food and agriculture world, are there any examples of effective ways of working with the land that provide hope for the future?

JH: I think of the milpas, holistic agricultural systems that have been passed down from our ancestors. These [intercropping] systems have lots of plants that have relationships with each other.

The milpas shows what is possible when everyone and everything is working together. It shows we have to work altogether in order for us to heal our environments, especially with climate change. Often, people feel like they shouldn’t be part of this conversation, but everyone plays a role like in the milpas. I am seeing that a lot in our generation, we’re more receptive to listening to one another and then the younger generation is even more open.

MF: Our readers are largely farmers and gardeners, but also people who care about where their food comes from. What would you want this particular audience to take away from your book?

JH: Just being open to listening to other stories. I speak to people from different communities with points of views that are often silenced. This is especially true with agriculture because, sometimes, we see farming just with ties to food, but in the book I talk about many cases where climate change has not just resulted in the loss of food for people but ecological grief.

These plants are relatives and Indigenous people experience a lot of emotions when climate change destroys their land because of this. Hopefully, this experience of ecological grief and ecological loss is something people can start thinking about and the scale of it that could happen if we don’t address climate change. And really, I hope this inspires people to make small steps toward cleaner lands.