When Lynn Cassells and Sandra Baer bought their plot of land in the Scottish countryside, they didn’t intend to farm on it. But the land had other plans.

When Sandra Baer and Lynn Cassells met in 2012 while working as rangers for the UK’s National Trust, they felt an instant connection, as if there were larger forces at work pushing the two women together, and they simply had to surrender to the journey. Before long, the two were more than colleagues, starting a relationship that would lead to a civil partnership a decade later. It was a similar feeling when they first laid eyes on Lynbreck Croft, the vast expanse of land in the northeastern tip of Scotland, in 2016.

The croft, situated in the middle of Cairngorms National Park, was up for sale, a rare opportunity. Baer and Cassells decided to have a look, although neither of them were Scottish nor had any background in farming. While growing up in Northern Ireland, Cassells loved to explore the countryside, and she studied archeology in university. Baer grew up in Switzerland, eventually moving to Canada to train horses. The two women have always chased new experiences, longing to be outdoors, restless at the thought of staying still. And yet, when they laid eyes upon the rolling hills, lush with purple heather, they knew they were home.

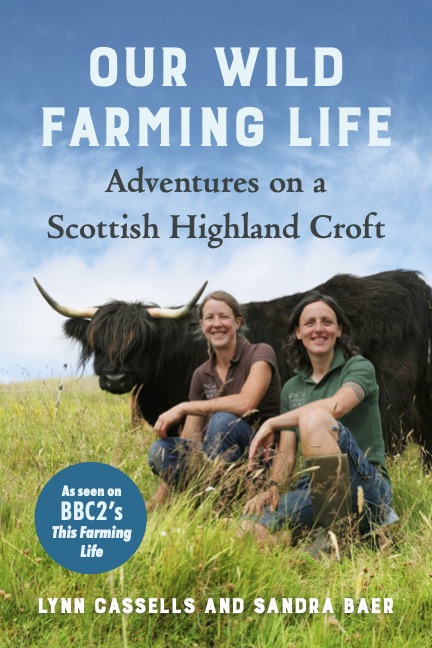

Their story was featured on an episode of the BBC’s This Farming Life in 2018. Now, in a new book, Our Wild Farming Life, Cassells and Baer detail how they found themselves becoming farmers, almost by accident, and what it takes to run a croft in the Scottish countryside. Modern Farmer spoke with Cassells about their experiences and how, as farmers, they are learning as they go.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Modern Farmer: Let’s start off with something that I don’t know if many people in America would know. What is a croft?

Lynn Cassells: It’s a really good question! It is uniquely Scottish. Crofting came out after the Highland Clearances, in the late 19th century, when a lot of the people that worked the land were chucked off the land and were resettled to these little plots. The plots were big enough that they could grow a little bit of food but not enough that they could kind of make a full-time living out of it. It meant that, quite often, they had to go and work on the land holdings that they’ve just been kicked off of. They fought back, saying, ‘We want to be protected and know that this will never happen again in the future.’ So the [Crofters Holding Act] was passed about a century ago, and [it] said that, if you are designated as a crofter, then you can never be kicked off the land again, if you work your croft.

Today, working the croft can mean any kind of real diversification. You can have a croft and run a glamping site, but it’s about having people on the land or in the community and having it be vibrant and socially viable, economically viable.

MF: What did you feel when you first saw the Lynbreck croft?

LC: We knew we were in trouble. When people come here, they’re totally blown away by the landscape, this really incredible mix of flat open bog, that then goes into this forest, and then culminates in this huge mountain range at the back end, and there’s like nothing in between. It’s really sort of quite a magical place, and it just looked like a little bit of paradise. So, for us, it was like, right, how are we going to make this work? We were looking at the land, and we were looking at the location, and we were looking at the buildings, and we were just thinking, ‘Oh, my God, this is heaven.’

MF: Throughout the book, you mention that you never meant to be farmers. There’s even a period where you’ve purchased the land, and you’re figuring out what you want to do with it. What was the tipping point?

LC: Farming really didn’t come into play until we were here. I think really, if I’m honest, the reason why farming didn’t come into our heads for such a long time was because we didn’t come from any farmer backgrounds. I’ve never trained in farming, neither had Sandra, then we both kind of had a career change in our late 20s into conservation. We were working in practical land management, but it’s like tree felling and surveying, and we got immersed in the rewilding movement. So we weren’t thinking about farming at all, we were in the rewilding world. And then we started to think but actually, this doesn’t make any sense. You can’t exclude people from nature, because we’re part of it. Why can’t we still work this land? Why can’t we use it to produce food, but do it in a way where we’re harmonizing with all this incredible environment?

MF: Did you ever second-guess the decision?

LC: Endlessly. We threw everything into this, all of our life savings. So, when we got here, we didn’t have any surplus cash at all to spend on the place. We were conscious that we had money to repay. We started to look at what opportunities were available in terms of access to different parts of grant funding, and that was really important to help us set up.

Because we had very little to start out with, it made us really cautious about what we were signing up to in terms of how we were going to approach farming. We were never going to be able to approach farming in a way where we were going to have a big tractor, we were going to be plowing the fields, because we don’t have any of the money to do any of that. Instead, what can we do for free? And actually, is that going to be a better solution for us in the long term, because we’re not tying ourselves up to reseeding every few years or the maintenance on our equipment.

MF: Were you learning on the job as you went?

LC: Yeah, exactly. And the core of our business is farming to produce food. We do diversify, like a lot of farms do, for additional income, but if we didn’t have our core farming business, then we would have nothing. We have a small fold of Highland cattle, and we finish some every year for beef. We do releases of pork every few months. We have flocks of layer hens for pastured eggs, and we keep bees for honey. We also installed a small micro-butchery on the croft, so we now do a lot of our own butchery. We’re always thinking, rather than just get more animals, what else can we do?

MF: And it’s just the two of you on 150 acres?

LC: Yeah, just the two of us. It’s been really interesting as our journey with Lynbreck has evolved. Our goal was always about us being back on the land. In addition to the farming business, one of our main jobs is our kitchen garden. As we’ve progressed, and as more and more people have become interested in what we’re doing, we do get a lot of people asking if they can come work for us or volunteer. We’ve really had to look at that and think if that is taking us in the direction that we want to go in. We really want to share what we do, because we want to help other people get on this journey. We want to educate people, share our learning… but also, this is our home. And we really love doing a lot of this work. That’s the fact of it.

Sometimes, it’s really hard, because people expect you to grow. But we’ve actually fought against that to stay small. We can provide everybody with incredible pork, we can provide everybody with incredible eggs. But wouldn’t it be incredible if there were more small farms available that were doing this kind of thing that we could hook up with?

MF: To some, your story can seem quite romantic. What would you tell someone who is on the verge of doing what you two did?

LC: It’s everything that you think it will be and it’s nothing like how you think it will be, both in equal measure.

It’s so dreamy, isn’t it? I’m going to move to the land, we’re going to have some chickens, it’s gonna be lovely. And we’re gonna have lots of time for tea and coffee and just observe the landscape. And bills don’t exist. We were a bit guilty of that. Not because we wanted to dream more, but because we just so desperately wanted to get away from our urban lives. Now, there are still pressures, there are still stresses that come with it. But the beauty of being able to sit down in an evening after a hard day’s work, and you eat this incredible meal, and you go, ‘Every single thing on this plate I produced. I grew the potatoes, I baked the bread, I raised this animal whose meat I butchered.’ You can’t underestimate that. So, for anybody who wants to follow this way of living, you have to do some soul searching on it. But if you work at it, it’s pretty awesome.

I loved your being able to live the land…I didn’t love that you kill animals..maybe you should do a farm sanctuary.