Freshwater supplies are under stress as the global demand for food increases. Through selective breeding, one company is creating crops that can be irrigated with salt water.

The vast majority—97 percent—of the earth’s water is salt water found in our oceans. Another two percent is stored in ice caps or glaciers. That leaves just one percent of all water on earth for regular human use: eating, drinking and growing food. And we’re dealing with an ever-dwindling supply. A 2013 study showed that about 40 percent of the world’s population lives in regions where demand for water exceeds supply.

When it comes to the freshwater supply that we do have, we use about 70 percent of it for irrigation. Estimates out of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization show that, by 2050, we’ll have to increase our global food supply by 60 percent. But we only have the freshwater resources to increase food supply by 10 percent. We literally do not have enough water to grow the food we will need in the coming decades.

Unfortunately, you can’t water plants with salt water because it’s too dense. The salt weighs the water down, and the plant isn’t able to absorb it through the soil. Instead, the higher salt levels will actually leech water out of the plant, and it will eventually shrivel and die.

But what if we could change that?

There have been attempts and studies before. A British company created an irrigation system that relied on salt water, and a Dutch farmer experimented with degrees of salinity on his row crops in 2014. Earlier this year, the USDA awarded a $10-million grant to researchers at the University of Florida and Clemson University who are looking at introducing salt water into irrigation. But one company is coming at the issue from a different angle: the crops themselves.

Tomatoes grown with salt water at Red Sea Farms. Photography courtesy of Red Sea.

The aptly named Red Sea Farms, based in Saudi Arabia, is working to create plants that can be irrigated with salt water. Through selective breeding, the team at Red Sea is upping the salinity tolerance of crops, creating hardier crops able to thrive in salty conditions. “We’ve done testing from a high-tech, very controlled greenhouse to an open field in Egypt,” says Ryan Lefers, CEO and co-founder. “When the conditions are really difficult—it’s hot, it’s salty, it’s dry—that’s when you see the real benefit of our rootstocks. In some of our early-stage testing in Egypt, we’ve seen up to double the yields in those really difficult conditions.”

Founded in 2018 through the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, the company studied common crops and the difficulties with growing them in desert regions without huge amounts of energy and water resources. Together with his co-founder, Mark Tester, Lefer began looking at tomatoes and their wild cousins. There are some breeds of wild tomatoes that grow fully in seawater, but they don’t produce palatable fruit. Tester and Lefer worked to get the salinity tolerance of those wild tomatoes into our everyday tomato plant.

“[Tester] had an ‘aha’ moment about three years ago, where he realized that a lot of greenhouse tomatoes are actually grafted,” says Lefer. “So, he could focus on developing a rootstock that had very good salinity tolerance, as well as heat tolerance, and then it just progressed from there.”

The tomatoes grown by Red Sea are typically sweeter than other grape or cherry tomatoes, as the plant produces more sugar to counteract the higher salt levels. Red Sea already sells some varieties of its tomatoes across Saudi Arabia, and it is working on growing peppers, cucumbers, squash and melons. Lefer says they’re not quite as far along with some of those plants, because they have a different plant and root system. But with plants that are grafted, such as pumpkins and watermelons, the process is largely the same.

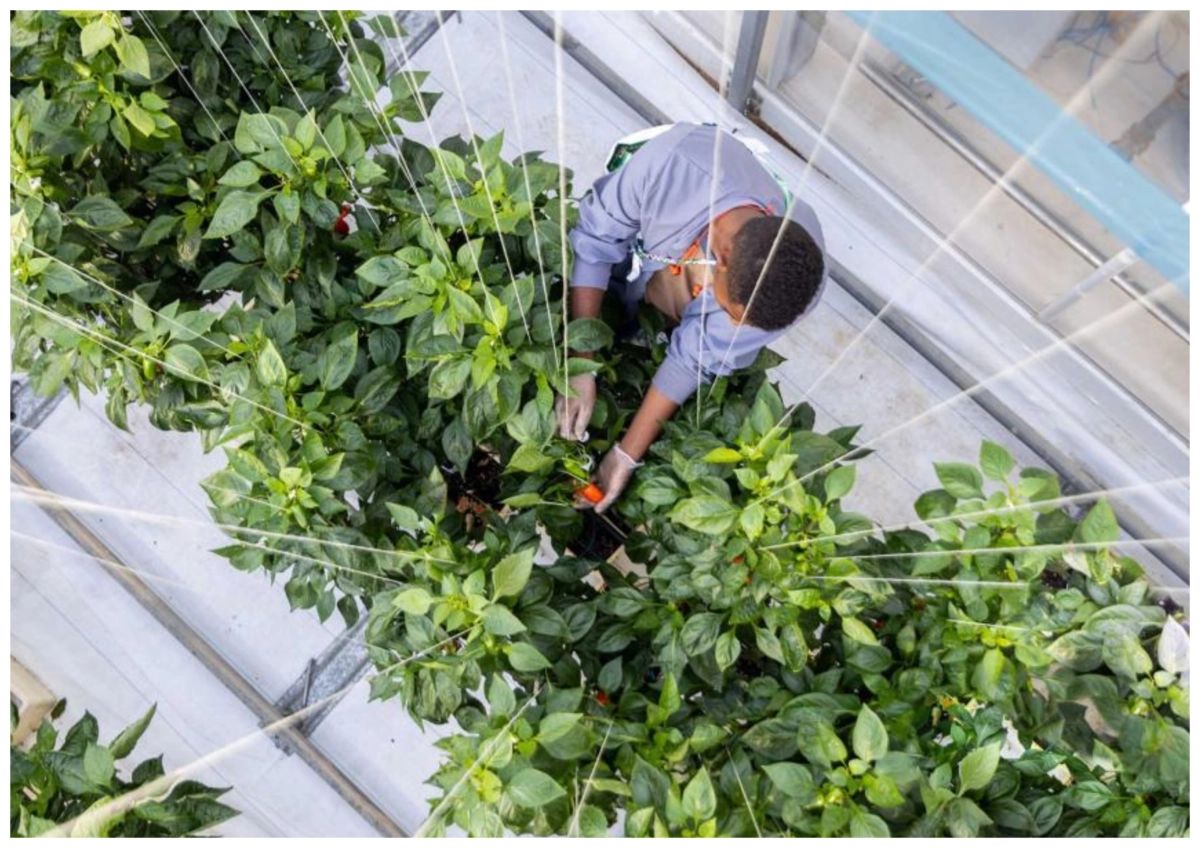

Photography courtesy of Red Sea Farms.

Beyond selling the actual fruits, though, Red Sea is working to get its seedlings into the market, so growers can bring salt-water-tolerant plants to their local areas. “We’re starting to onboard nursery partners that can license the technology, so they would sell the seedlings into the market.” Right now, Lefer and his team utilize their own greenhouses and nurseries to grow seedlings and will also look to sell them to consumers.

The surprise benefit of growing salt-tolerant plants within a greenhouse system is that it could actually help with overall water usage and consumption. In a hydroponic system, water is recirculated. But ,as that water recirculates, the sodium chloride in the water builds up. Growing plants with higher salinity tolerance allows you to use that water longer, because the plants have a resistance to those buildups. “[That can], therefore, reduce fertilizer inputs and also reduce discharge of water that’s both salty and has a lot of fertilizer, which tends to go into a lagoon.”

Of course, there are concerns about using salt water in open fields. If you exclusively irrigate with salt water in one area, the salt will build up and the field could become hostile to other plants in the future. Lefer says keeping this in mind and keeping a firm hand on the crop rotation and management is the best way to prevent this. “It all comes down to management,” he says. “When irrigating with salt water, one must carefully consider soil type and also manage irrigation and crop selection in a proper way to leach salts out of the root zone.”

Checking saline levels at Red Sea Farms.

As our available supply of freshwater lessens, desert farmers will have to make some difficult decisions. They can grow fewer crops or move away from food crops into desert-friendly plantings. Or maybe they will have to stop farming altogether. Irrigating with salt water could allow farmers in arid regions to grow more crops or to expand the array of plants available to them. Lefer says he and Tester started their research with the goal of making farming easier in the worst conditions, but he’s found that this research has applications all over the world.

“We were looking ahead to the future by focusing on a present reality for a marginal section of agriculture,” says Lefer. “What’s happened is that, because we were focusing on those marginal conditions with high heat and high salt, it’s benefited back into mainstream agriculture, because mainstream agriculture is now facing these conditions more and more.”

Great story. Do the tomatoes taste saltier than those grown with fresh water?

Doesn’t salt water kill the the soil itself?

Sounds great, needs to go worldwide.

To answer David’s question: the article indicates that the tendency is to create sweeter fruit as the plants compensate for the salinity of the water.

“The tomatoes grown by Red Sea are typically sweeter than other grape or cherry tomatoes, as the plant produces more sugar to counteract the higher salt levels.”

Breeding crop varieties for salt water resistance should be considered as immediate requirement and Governments provide proper funds.