In Milked, journalist Ruth Conniff explores how American reliance on Mexican labor has bonded two seemingly opposed groups.

Since 2003, the US has lost about half of its licensed dairy farms. However, the number of cows producing milk has stayed relatively steady. Take Wisconsin, for example. In 2004, the state was home to less than 16,000 dairy farms. In 2021, that number dropped in half, to less than 7,000 farms. But the number of cows in the state? That didn’t change. There are still about 1.2 million cows in Wisconsin. They’re just part of much bigger herds these days. That means that smaller farms are getting squeezed out in favor of industrial farming and Confined Animal Feeding Operations, commonly referred to as CAFOs, in which large numbers of animals are raised, generally in confinement, and feed is brought to them, rather than letting them graze.

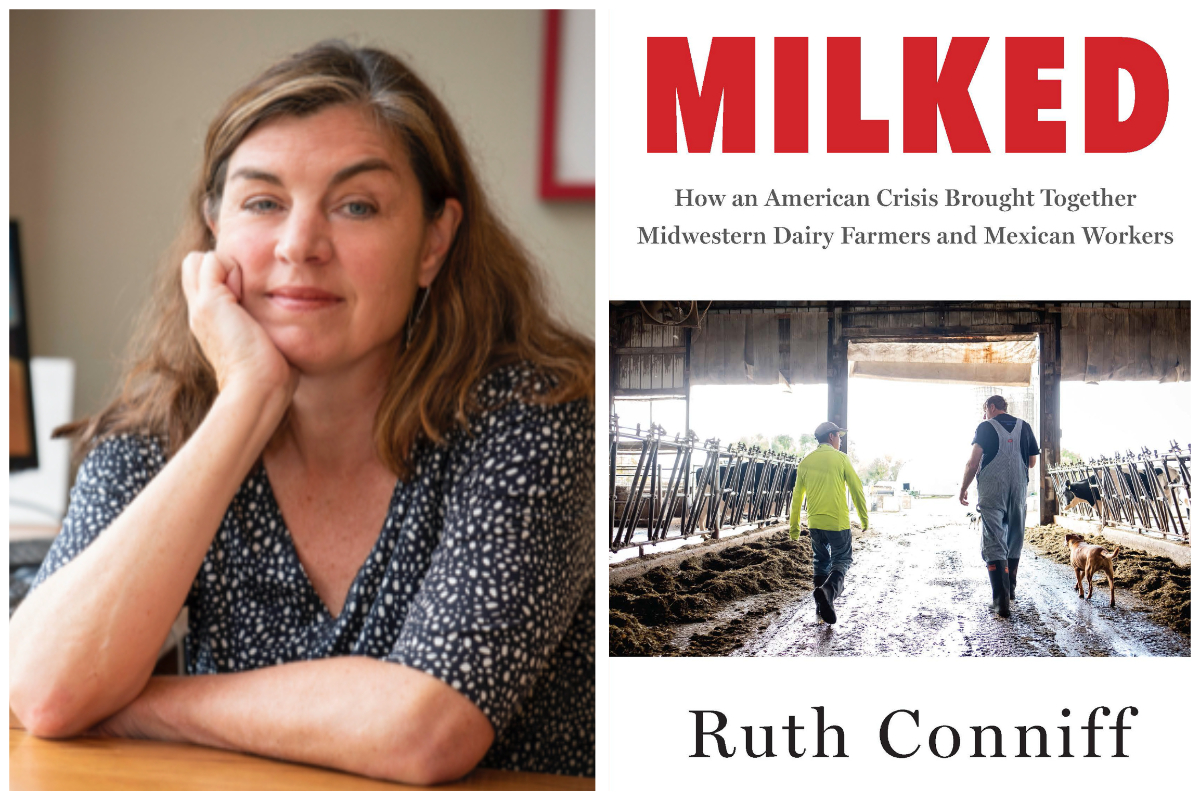

As Ruth Conniff reports in her new book, Milked: How an American Crisis Brought Together Midwestern Dairy Farmers and Mexican Workers (out today from The New Press), the reduction in American dairy farms has impacted generations of people and moved beyond borders. The longtime journalist and editor-in-chief of the Wisconsin Examiner spent a year looking closely at the changes in American dairy farms. A common element on most farms she visited: Mexican workers. Conniff set out to explore how American reliance on Mexican labor bonded these two seemingly disparate groups so tightly.

As Conniff writes, the fall of dairy farms on American soil coincided with a period of crisis in Mexico, which sent “millions of subsistence farmers off their land, sending them into the cities and walking across the desert looking for work.”

The impetus for these concurring dilemmas, says Conniff, was the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, which was enacted in 1994. Under NAFTA, goods could be sold across the three participating countries (Canada, Mexico and the US) with reduced tariffs—or no tariffs at all. Cheap US corn flooded the Mexican market, causing thousands of Mexican farmers to go bankrupt when they could no longer sell their crop locally, eventually causing them to need to migrate north in search of work. “The rural parts of Mexico are suffering, in a more intense way, from some of the same forces that are afflicting rural parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota,” says Conniff. “Big Food and Big Ag are making it really hard to make a living for smaller farmers.”

Those Mexican workers will often cross the US border illegally to work on dairy farms. While the H2-A visa allows agricultural workers entry to the country, it’s a temporary visa designed for seasonal work. Dairy farming, on the other hand, is year-round. No such visa exists for those workers.

RELATED: Can Biodigesters Save America’s Small Dairy Farms?

“Circular migration is sort of a hallmark of Mexican workers in the United States,” Conniff explains. She describes a federal program from the 1950s, aimed at supplementing a labor shortage after World War II, which brought undocumented workers across the border to work on farms and in agricultural processing. “The flow back and forth across the border was very easy. Now, we have a militarized border and a moral panic about immigration, but people are still coming. And they’re still carrying whole US industries, especially agriculture, but they’re doing it under really dangerous conditions. And it’s really expensive.”

Conniff focused on a group of farmers in Wisconsin, each of whom employs Mexican workers. In alternating chapters, Conniff tells the stories of the farmers and then their workers, moving swiftly across the border to paint a picture of how and why these folks are tied so tightly together—especially in the wake of the 2016 presidential election.

“Most of the [farmers] I talked to voted for Trump, in spite of the fact that they are deeply involved with and completely economically dependent on these undocumented workers from Mexico,” says Conniff. She describes one farmer named John who, at first, had reservations about employing undocumented workers. Desperate, he cast his doubts aside.

“The documents John’s employees show him are almost certainly fake,” Conniff writes in the book. “John takes a don’t-ask-don’t-tell approach. Even his most ardent Trump-supporting neighbors agree with him on this issue: American agriculture would collapse without undocumented immigrant labor.”

Part of the reason these farmers can hold these seemingly opposing views, Conniff reasons, comes back to NAFTA. Trump promised to do away with the agreement throughout his presidential campaign, once calling it the “worst trade deal” the US had ever signed. (In 2020, with NAFTA dissolved, the three countries entered into the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement instead.) “The way the farmers themselves explain it is to say ‘he doesn’t really mean it,’ or ‘yeah, he’s a loudmouth, but he’s going to do the right thing.’”

In that way, says Conniff, farmers were able to turn a blind eye to the president’s less palatable traits, such as Trump describing Mexicans as rapists, after stating “they’re bringing” drugs and crime across the border. Perhaps this was a bout of cognitive dissonance, or maybe it was willful ignorance. Either way, Conniff describes the American farmers bonding with their Mexican workers, even while some farmers still voted against their workers’ best interests.

Many of those workers are conflicted as well. Just as important as speaking with the farm owners was hearing directly from the Mexican farmworkers. For many of the folks with whom Conniff spoke, the money they can make in the United States keeps their families fed and housed back home in Mexico. Conniff interviewed several farmers who sent money back to build houses, put their kids through school or started businesses. Still, their lives are often difficult. One woman Conniff interviewed, named Blandina, says that the farmers she and her husband work with treat them well, but there’s the expectation that they will work constantly and for less money than American colleagues. “Our labor is exploited,” Blandina told Conniff. So Blandina and her husband Pablo keep their goals in mind: sending their daughter to university and eventually moving home.

RELATED: American Agriculture’s Reliance on Foreign Workers Surges

Of course, not every farmworker goes back to Mexico. As people build lives and communities in the United States, it becomes harder to leave. Conniff interviewed one family whose two sons were born in Wisconsin, making them US citizens. With kids, it’s even harder and more expensive to traverse the border, so the parents often stay put for years. And then “the kids go to high school, and potentially on to college in the United States, and they cannot imagine going back to subsistence living in a remote village in Mexico,” says Conniff. Now, there are “parents who have always dreamed of going back…and you have the kids who become increasingly distant from that idea.”

That’s where groups that advocate on behalf of agricultural workers come in. There are campaigns across the country pushing for legislation to help undocumented workers and their families. Conniff writes about the Wisconsin Farmers Union, which works in tandem with immigrant rights activists to push for driver’s licenses for undocumented workers. There’s also Voces de la Frontera, a worker-led organization dedicated to immigration reform and workers’ rights. While those groups, and others like them, push for change, Conniff says it’s important to take stock of where we are presently. “We have this two-decade-old economic relationship that is absolutely baked into the way we run our dairy and agricultural economy,” she says. “It’s a fantasy to think that you’re just going to build a wall, and this will end, and it will be the best economically for the United States.”

Instead, Conniff says that after her year reporting this book, she has come to recognize the importance of a legal year-round visa for agricultural work as a clear first step. The idea has bipartisan support, and it simply acknowledges the real work that people are doing. “Then the bigger question is, how do people live livable lives? How do we have sustainable work lives and sustainable food, and people don’t have to smuggle themselves in the trunk of a car across the border?” Conniff asks. “And how do we [preserve] those beautiful small farms that have made Wisconsin such a lovely place?”

Milked reaches far beyond the people its author profiled. The stories are personal and universal, stretching into farms and fields across the country and over borders. Farmers and workers will continue to be bonded together by the economic demands of both countries.

In the meantime, the number of dairy farms in the country continues to drop.

We have a similar problem in New Zealand, young people do not want to work on farms despite huge increases in wage rates. We rely almost entirely on workers from the Phillipines for dairy. The dairy farmers are accused of dirtying the ground water supplies and streams so there is a negative view of their activities. All cows are grass fed and there are no barns, what do your farmers do with all the waste from the barns?