Since 1974, the Suffolk County initiative has helped save more than 11,000 acres of Long Island farmland from development.

Drive through New York’s western Long Island on any given afternoon—particularly as rush hour approaches—and you’ll be moved not by the idyllic rolling hills of verdant farmland but, rather, by the throb of traffic on the LIE (local parlance for the ever-crowded highway known as the Long Island Expressway).

The densely populated, 118-mile-long island, which stretches east from New York City to the outer reaches of Greenport and Montauk, was once home to an agrarian lifestyle. Then, in 1947, 4,000 acres of potato farms in Nassau County were converted into what would be known as the country’s first suburban community: Levittown. That planned community would also herald the island’s suburban sprawl, making way for other like-minded ideas. By the late 1960s, Long Island looked a lot less like farmland and a lot more like an extension of the city.

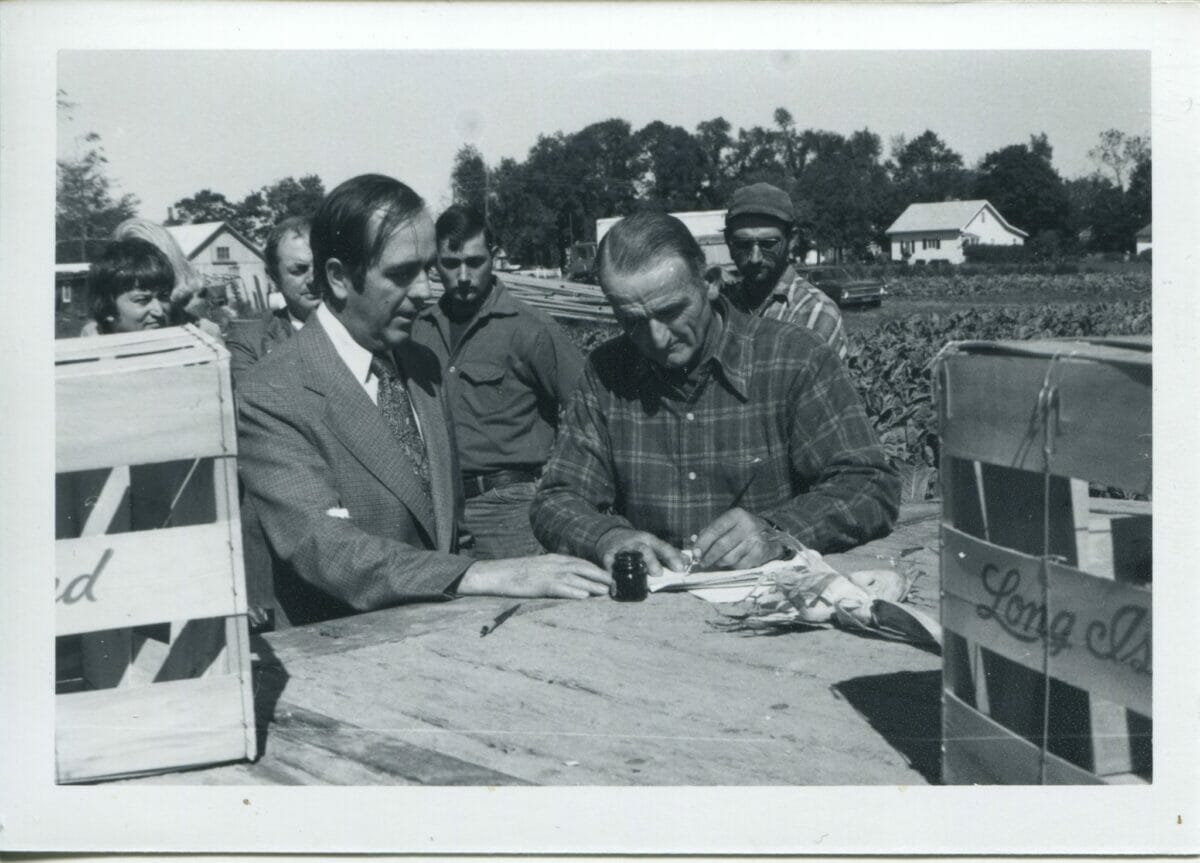

Long Island was becoming less agrarian, and then-county executive John Klein realized that this decimation of land was going to become a problem. In 1974, with his help, the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program was launched in an attempt to curb the sprawl. It was among the first programs of its kind in the nation to protect working farms.

“The county would buy the development rights to farmland and leave the residual land itself still in private ownership from the farmers,” says Robert Carpenter, director at Long Island Farm Bureau.

The program, Carpenter says, offered the farmers a financial incentive while keeping the land in their hands. Meanwhile, farmers would continue to pay taxes on the land and continue to maintain it, which simultaneously benefitted the government. “It was really a win-win situation at that point for both the government and the farm community,” says Carpenter.

In 1977, George C. Reeve, seventh-generation farmer and owner of Reeve’s Farm, gave up development rights to his 84-acre farm, which is still in operation today.

The result, according to records kept by the Suffolk County Farmland Development Rights Program, has been a total of 11,000 acres of protected farmland within the county since the program’s inception and more than 20,000 acres of protected farmland within the county through the combination of additional county, town and other preservation programs.

“I think that if there was no farmland preservation program, or no open space program, we would see, basically, you know, Babylon, Islip, Huntington, develop like that, all the way out to the East End, for certain,” Carpenter says, comparing Long Island’s North and South Forks to the highly developed areas of Nassau and western Suffolk counties.

In this fundamental way, he says, the program has been a success, and, to some degree, a benchmark for other programs around the country. Connecticut’s statewide and voluntary Farmland Preservation Program, for instance—developed four years after Suffolk County launched its program—has preserved 45,000 acres of land and seeks to preserve 130,000 acres in the long term. New Jersey’s Farmland Preservation Program was also established in the early 1980s, helping to save some 69,500 acres of farmland by 2000.

RELATED: Study Finds 1 Percent of Farms Own 70 Percent of World’s Farmland

The need for such programs is still felt today. According to a 2020 report from American Farmland Trust, 11 million acres of American agricultural land was lost to development between 2001 and 2016.

Perhaps the reason for the Suffolk program’s success, Carpenter and others say, is that it has targeted a group of landowners who have been the most likely to take advantage of it. “Most farmers, their largest asset by far is the farm itself,” says Kareem Massoud, winemaker at Palmer Vineyards and Paumanok Vineyards on the North Fork of Long Island and president of Long Island Wine Country. “And most farmers are stuck with a situation where the crops that they grow are not that profitable and Mother Nature is your partner.” That twinned relationship makes farmers vulnerable, says Massoud, and it also makes them susceptible to appeals from developers, because the work is hard and the reward is often small.

Another reason the program worked—and has continued to work—says Massoud, is that the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program has relied on the market to dictate land value. “Farmers aren’t stupid. They’re business people, too,” he says. “And, after all, for most farmers, this is their life savings, essentially, tied up in the land, and, so, in order to make it work, you have to pay fair market value.” When farmers cede development rights to the county, they do so at a rate that competes with a real rate that they might get from an actual developer and that, says Massoud, does make an appreciable difference when it comes to incentivizing preservation.

For farmers entering the business, properties that have already sold off development rights may also prove more attractive. “If your true purpose is to farm, with no consideration to future generations and what their desires might be, purchasing property or even leasing property to grow that has no development rights intact is very affordable,” says Christine Tobin, owner of Mattebella Vineyards in Southold, New York.

Tobin, who owns 21½ acres with her husband Mark, says that the majority of their property—all but three acres—lacks development rights and, as a result, has reduced property taxes. “The real estate tax on that component of such a large piece of property is under $1,000 a year,” she says.

But the true legacy of the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program has been less—less sprawl and fewer houses on eastern Long Island, where wineries and farmland continue to populate the landscape. If the standard home on the East End is built on an acre of land and the Preservation Program lays claim to 11,000 acres of protected land, one can imagine 11,000 homes in its place, where vineyards, cornfields and apple orchards still have room to grow.

I live on Long Island and I used to be a working farmer upstate. Mostly the “farms” on Long Island are either rich folk’s hobbies, such as wineries, or sod farms and nurseries catering to suburban homes. I can’t imagine running a real working farm out here. It was a mistake to develop a limited access, limited resource, island. Our water table is being drawn down and salt water is infiltrating the ground water. L.I. has been turned into urban sprawl, much of it uncomfortably similar to the Bronx (and not the good parts). Government corruption is outrageous: we regularly… Read more »