The post Why is Turkey the Main Dish on Thanksgiving? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Almost 9 in 10 Americans eat turkey during this festive meal, whether it’s roasted, deep-fried, grilled or cooked in any other way for the occasion.

You might believe it’s because of what the Pilgrims, a year after they landed in what’s now the state of Massachusetts, and their Indigenous Wampanoag guests ate during their first thanksgiving feast in 1621. Or that it’s because turkey is originally from the Americas.

But it has more to do with how Americans observed the holiday in the late 1800s than which poultry the Pilgrims ate while celebrating their bounty in 1621.

Did they or didn’t they eat it?

The only firsthand record of what the Pilgrims ate at the first thanksgiving feast comes from Edward Winslow. He noted that the Wampanoag leader, Massasoit, arrived with 90 men, and the two communities feasted together for three days.

Winslow wrote little about the menu, aside from mentioning five deer that the Wampanoag brought and that the meal included “fowle,” which could have been any number of wild birds found in the area, including ducks, geese and turkeys.

Historians do know that important ingredients of today’s traditional dishes were not available during that first Thanksgiving.

That includes potatoes and green beans. The likely absence of wheat flour and the scarcity of sugar in New England at the time ruled out pumpkin pie and cranberry sauce. Some sort of squash, a staple of Native American diets, was almost certainly served, along with corn and shellfish.

A resurrected tradition

Historians like me who have studied the history of food have found that most modern Thanksgiving traditions began in the mid-19th century, more than two centuries after the Pilgrims’ first harvest celebration.

The reinvention of the Pilgrims’ celebration as a national holiday was largely the work of Sarah Hale. Born in New Hampshire in 1784, as a young widow she published poetry to earn a living. Most notably, she wrote the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

In 1837, Hale became the editor of the popular magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book. Fiercely religious and family-focused, it crusaded for the creation of an annual national holiday of “Thanksgiving and Praise” commemorating the Pilgrims’ thanksgiving feast.

Hale and her colleagues leaned on 1621 lore for historical justification. Like many of her contemporaries, she assumed the Pilgrims ate turkey at their first feast because of the abundance of edible wild turkeys in New England.

This campaign took decades, partly due to a lack of enthusiasm among white Southerners. Many of them considered an earlier celebration among Virginia colonists in honor of supply ships that arrived at Jamestown in 1610 to be the more important precedent.

The absence of Southerners serving in Congress during the Civil War enabled President Abraham Lincoln to declare Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863.

Turkey marketing campaign

Godey’s, along with other media, embraced the holiday, packing their pages with recipes from New England and menus that prominently featured turkey.

“We dare say most of the Thanksgiving will take the form of gastronomic pleasure,” Georgia’s Augusta Chronicle predicted in 1882. “Every person who can afford turkey or procure it will sacrifice the noble American fowl to-day.”

A second one is that turkey is also practical for serving to a large crowd. Turkeys are bigger than other birds raised or hunted for their meat, and it’s cheaper to produce a turkey than a cow or pig.

The bird’s attributes led Europeans to incorporate turkeys into their diets following their colonization of the Americas. In England, King Henry VIII regularly enjoyed turkey on Christmas day a century before the Pilgrims’ feast.

Christmas connection

The bird cemented its position as the favored Christmas dish in England in the mid-19th century.

One reason for this was that Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” sought redemption by replacing the impoverished Cratchit family’s meager goose with an enormous turkey.

Published in 1843, Dickens’ instantly best-selling depiction of the prayerful family meal would soon inspire Hale’s idealized Thanksgiving.

Although the historical record is hazy, I do think it’s possible that the Pilgrims ate turkey in 1621. It certainly was served at celebrations in New England throughout the colonial period.

Troy Bickham is a Professor of History at Texas A&M University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The post Why is Turkey the Main Dish on Thanksgiving? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Haunting of the Farm appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>This is the story that guests at one haunted farm are told when they visit during the Halloween season. Another haunted farm attraction in Alabama promises to bring you closer to the “creatures and killers” of the farm. Another, in South Carolina, invites you to its “desolate farm” where the inhabitants are hoping “to make you this year’s harvest!”

Haunted farm attractions are not homogenous—some are real working farms that incorporate haunted attractions into their seasonal offerings as a way to supplement farm revenue and connect with the community.

Other haunted farm attractions aren’t farms at all but haunted house businesses that use the idea of a haunted farm to inspire terror. The popularity of this concept is more than a fun seasonal activity, though. It also engages with longstanding narratives about rurality, performing them for a fearful audience.

Haunted houses and cultivating screams

Growing up a theater kid, it wasn’t hard for Betty Aquino to fall in love with farm haunted houses. After college, she found herself working for a haunted house attraction on a farm as a make-up artist. Aquino went on to do her graduate work at George Mason University and completed her thesis work on how haunted house attractions on farms rely on rural tropes that can be both empowering and problematic.

For small farms that face pressures from big agriculture and high land prices, using things such as haunted house attractions to supplement income is a way to adapt. But, in some cases, to make it work, haunted farmhouses often rely on the stereotypes of the rural “other”—the idea that whatever happens on a farm after dark is scary and unknown.

Haunted houses are more story driven than other farm attractions such as corn mazes or pumpkin picking, often relying on a pre-constructed narrative. Capitalism is a driving force in these narratives, says Aquino, informing depictions of gender, race and class and occasionally referencing a community’s own trauma. In one farm haunt she visited in Michigan, Aquino felt that what she saw was representative of the automobile industry’s history in the state. The villain in the story comes to the town and promises jobs, only to use dark magic against the town instead.

“One of their haunts has this narrative of a town that has lost its industry,” says Aquino. “And it is essentially this ghost town that’s very much a mirror of many towns in Michigan.”

The “ghost town” narrative was one Aquino saw a lot during her field research—as was “hillbilly horror.”

“I think those narratives are very reflective of their near-death experiences as farms,” says Aquino. “And they’ve had to pivot and rebuild their businesses.”

A haunted attraction that was once a farm. (Photography from Shutterstock)

The benefits of haunted houses

Although haunted houses existed in some form or another long before this, historian David Skal argues that the popularity of haunted houses in general grew significantly after Disney opened the Haunted Mansion attraction in 1969.

As we wrote a few years back, Halloween is a holiday with deep agricultural roots. It marks both the end of the harvest season and a time of year when the connection to the spirit world is the strongest. Opening haunted houses on farms is a natural extension of this connection.

Perhaps thanks to the associations between Halloween and agriculture, many farms have had success introducing haunted farm attractions into their business. According to the USDA, between 2002 and 2017, agritourism revenue more than tripled. This figure represents more than Halloween attractions, but the fall season is a big draw for a lot of farms.

Kevin McCall, managing partner of McCall’s Pumpkin Patch in Moriarty, New Mexico, says that adding haunted attractions to the farm’s offerings has been a helpful source of revenue. The farm started by introducing a haunted hayride, but “it’s hard to haunt on a hayride,” he says. Then it added a haunted corn maze with about 50 actors and props. In the 2000s, the farm converted its cattle barn into a haunted barn attraction. It’s woven all together with the fictional narrative of a farmer who, in response to an interstate being built through the farm, begins slaughtering tourists.

McCall’s Pumpkin Patch draws visitors from Albuquerque and Santa Fe, and this season, it sold out. This showcases the significant benefit that Halloween haunts can have for farms—McCall says the business it gets from haunting allows more freedom and security with the agricultural side of the business.

“It’s allowed us to be a very different type of farmer,” says McCall.

A person dressed up for Halloween on the farm. (Photography from Shutterstock)

The future of haunted farm attractions

In Rural Remix’s new podcast, “The Rural Horror Picture Show,” hosts Susannah Broun and Anya Petrone Slepyan talk about classic films in the folk horror genre and how depictions in horror films such as “Deliverance” and “The Hills Have Eyes” portray rural spaces as scary places where horrors are born. They point out that this narrative has old roots in popular culture.

When it comes to the future of haunted house attractions on farms, Aquino concludes that these haunts are a space of evolving rural identity.

As a genre, she says, horror has the ability to critique and interrogate many institutions and ideas. Rural communities are also capable of challenging the status quo—through things such as unions and initiatives such as the Black Appalachian Coalition, which works to fight the erasure of Black people from narratives about Appalachia. Rural haunts can be a space to question tropes about rurality.

“I hope that there is a return to radical roots in rural spaces,” says Aquino, “and that we continue to see more diversity in the narratives and the people working at these places.”

Halloween and agriculture have always been linked, and seasonal haunts give us the opportunity to understand that connection in today’s context.

The post The Haunting of the Farm appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post West African Yam Festivals Celebrate Harvest, Community and Life Itself appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>These are scenes from the Iluyanwa Yam Festival. Celebrations of culture, community and life, yam festivals occur throughout West Africa. The festivals are essential events; they mark the passing of another season, honor religious offerings and provide a cultural focal point for a whole town to converge around. It’s a community celebration, supported by local organizations or governments, bringing together dozens, hundreds or even thousands of people every year—all to celebrate the humble yam.

A scene from the Asogli Yam Festival in Ghana. (Photo courtesy of Ghana Broadcasting Corporation)

Frequently called the “yam belt,” West Africa accounts for 94% of the world’s yam production, with Nigeria alone producing about 50 million tonnes annually, more than two-thirds of the global yam crop. The cultivation of yams began in the region some 11,000 years ago, as a result of a cultural interaction between grain-crop agriculturalists who were being forced southward by the progressive desiccation of the Sahara and gatherers in the forests and savannahs of West Africa, who were eating wild yams but not yet cultivating them.

The yam is considered by most West African ethnic groups to be a symbol of fertility and the sustainability of life, and it often plays versatile cultural roles, used in inaugural, wedding and naming ceremonies. Yam festivals, which mark an important changing of the seasons, bring the community together to celebrate the harvest and give thanks to the gods.

“The festival is held in commemoration of the gods of the land for a good harvest season,” says Tatiana Haina, who creates food and travel vlogs on YouTube and covers the cultural festivals of her native Ghana. One such festival is the Krufie Yam Festival, celebrated by the indigenous people of Bredi, a community near Nkoranza in the Bono East region of the country. “The people believe the gods of the land have been very protective throughout the year and hence use the festival as a way of showing appreciation to the gods for their guidance and protection into a new bumper season,” she says.

West Africa produces nearly all the world’s yams. (Photo courtesy of Marthe Montcho)

Over the past decade, the ceremonies have become a significant contribution to West Africa’s tourism, bringing attention and tourists interested in the cuisine. Traditionally celebrated in the open like most food festivals, yam festivals across regions attract both thousands of locals and visitors from the United States, Canada, Netherlands and further afield. “There is usually a lot of chanting, singing, drumming, dancing and costume displays by the local people,” says Jahman Anikulapo, a Nigerian culture activist and archivist. He believes cultural festivals such as the yam festivals unite the community and stimulate a general feeling of camaraderie.

Yam festivals often encourage and reward agricultural production. For instance, among the Ewe people in Ghana and Togo, different farmers present their yams in a competition to be named “chief farmer” or “Yam King.” And because some ethnic groups, such as the Igbo, believe the productivity of the tuber crop to be influenced by spiritual forces linked with the earth, yam festivals become an avenue to offer thanks to the gods of the land.

In ancient days, the yam was a major crop plant in empire-states and kingdoms such as Ashanti, Dahomey, Nri, Ife and Benin, and before the harvest, festivals were often celebrated to mark a new year. “The festivals are particularly popular in the southeastern part of the country,” says Anikulapo. He recalls his stay in the state of Enugu, where yams were brought to a king’s palace and, after the affair was officiated by a chief priest, instructions were given to plant setts of yams to secure another bountiful harvest in the next year.

Women pounding yams. (Photo courtesy of IITA.org)

But yam festivals are not only celebrated today among the Igbo, Urhobo, Yoruba and Ijaw people of Nigeria. Outside the country, the festivals are prevalent among the Bono and Ashanti people of the Akan ethnic groups in Ghana; the Fon people of the Republic of Benin; the Ewe people in Togo, and the Ashanti and Anyi people of the Akan ethnic groups in Cote d’Ivoire.

As the Fon people of Benin have strong ties with the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Akan people in Cote d’Ivoire with their fellow ethnic group in Ghana, the festivals are celebrated with just as much pomp and procession. Traditionally, the newly harvested yams are not eaten until members of a particular group—usually the chief’s household or the chief priests—have partaken of the new crop. But, unlike other ethnic groups, a special celebration of the new yam is held exclusively by Fon women in certain clans, in which, after the sacrifice of a ram and fowl, the new yams are ritually pounded and, after being offered to deities, eaten by the women and children.

“The festival can be celebrated for a month. It depends on the location and the people involved,” says Haina. Among the Igbos and the Fon people, the festival is usually in late July or August, and it could span days. For the Yoruba people in Ekiti State, Nigeria, the feast is celebrated in August and spans a day or two.

The Ife king blesses the yams. (Photo courtesy of Ife City Blog)

Yam festivals are usually sponsored by the local community. “Support comes mostly from age grade groups [a form of social organization based on age], other social clubs and even some state governments in southeastern Nigeria,” says Anikulapo who, however, stresses the negligence of the government in supporting these cultural celebrations at the federal level. “There is no cultural policy in the country.”

The yam festivals are even being exported to the diaspora, where they are bringing together West Africans in Europe, Asia and the Americas. Organizations such as ICSN (Igbo Cultural and Support Network) of London, Isuikwuato Community of Qatar and Ndi-Igbo Germany of Frankfurt have kept the celebrations alive outside of the continent. The goal is to maintain tradition: If a rite or ritual is performed by the Bono people in Ghana, the same rite will take place for Bono people celebrating in the US. London’s Igbo community members delight in dancing and singing with the same vigor and splendor as their compatriots back in Nigeria. The celebrations might take place in halls, ballrooms or auditoriums, rather than in the open air, but that allows celebrants to issue invitations to select guests.

As the West African diaspora grows, yam festivals will travel to further corners of the globe, and include more and more people. More than just a one-off event, these festivals can open crucial dialogues about the balance of food tourism and food sovereignty, as more folks become acquainted with the yam.

The post West African Yam Festivals Celebrate Harvest, Community and Life Itself appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Payment for the Past: Recognizing Indigenous Seed Stewardship appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>How the seed passed from the Abenaki to white settlers is unknown, but what is known is that the genetic strength of Abenaki Flint is due in large part to the efforts of Abenaki seed breeders. And while the revival of Abenaki Flint (sometimes called Roy’s Calais) is unique, many of our familiar crops share a story of lost lineage.

Bringing a seed to a high level of performance is not accidental: Instead, it is a years-long process of observation, testing and careful stewardship. All of our most important food crops have undergone this process, yet many of the ties to their original producers have been severed. How we credit this work is a complicated process.

One of the methods of attributing value to seed creators is through royalties. Royalties are traditionally paid out to seed breeders who file a patent proving that their seed offers a new genetic profile with distinct characteristics from other seeds on the market. But what about the hundreds of years of foundational development before the common practice of patents and royalties? How do we recognize some of the most important seed architects?

In 2018, in recognition of this question, Fedco Seeds designated Abenaki Flint as “indigenously stewarded,” along with a handful of other varieties, and started allocating 10 percent of the proceeds from seed sales to a donation fund under its Indigenous royalties initiative.

Nikos Kavanya, seed branch co-ordinator at Fedco Seeds, was responsible for implementing Fedco’s program. “The impetus came from my sense of justice,” Kavanya said in an email. “For me, honoring our debt to the goodness and beauty of the past, especially for something as vital as seed, is a core value.”

Fedco was already paying royalties to independent seed breeders, but Kavanya felt that the foundation of some of that breeding work was going unrecognized and unrewarded.

“We were paying current breeders for seed that they had developed—but which had been bred before by many tribal peoples, whose work had, in many cases, been stolen,” said Kavanya.

“We exist in an industry that tends to be very pro intellectual property rights,” says Courtney Williams, Fedco Seeds’ co-ordinator and product developer. Of the Indigenous royalties program, she says the company wants to “value [the Indigenous work] in a way that is akin to valuing these intellectual property constructs awarded by patent offices.”

Determining which varieties to designate was the most challenging part of implementing the program. It is difficult to narrow down which crops deserve designation and harder still to confirm the lineage. How do you trace the story of something as complicated as a seed, small enough to fit in a pocket, and—up until recently—difficult to genetically verify?

“A case could be made that all of the seeds we sell were Indigenously derived,” said Kavanya.

Hopi Blue Corn. (Photo courtesy of Fedco Seeds)

The first stage of Fedco’s project was to designate varieties with the most overt connection, such as those with a tribal affiliation in their name, such as Hopi Blue Corn, Jacob’s Cattle Bean and Waneta Plum.

Choosing to call the designation Indigenous royalties was also a decision based on ease of communication, more than precision of the term. “We were already distributing ‘breeders royalties’ to some of the independent breeders whose seed we sell and so it felt like an easy shift for our customers to make,” said Kavanya.

Royalties traditionally refer to a direct payment made to an individual or company, but in this case, due to the difficulty of determining provenance, the proceeds are pooled. Therefore, Kavanya and her co-workers at Fedco decided to name a single beneficiary: a local project called Nibezun that crosses tribal affiliations to reach a broader constituency. Nibezun is a registered non-profit that operates on 85 acres in Passadumkeag, Maine, with access to Olamon Island, the original home of the Penobscot Nation and Abenaki confederacy.

Through the allocation of 10 percent of seed sales, along with direct donations from customers, Fedco paid out about $10,000 in Indigenous royalties last season.

In 2018, when Kavanya first started exploring a method to pay homage to indigenous breeders, she met with other seed sellers to brainstorm and explore the practical steps. Following up with those that sat around the table with her, she says she doesn’t see any evidence of implementation.

“I couldn’t find any of that work continued. It’s disheartening. There was a certain momentum at the time,” said Kavanya. She cites two possible obstacles. The first is with scale. For some companies, “the amount of seeds they are selling is so small, it felt sort of futile,” said Kavanaya. The second is with general opposition to the imprecision of the vocabulary itself. Using the word “royalties” was an unpopular decision with both sellers and Indigenous groups.

Because the money from all the designated seed varieties is pooled and not tagged to individual tribal breeders, “it is not terminology that everyone thinks is most representative,” writes Kavanya. An alternate name for the practice, which emerged from the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network, is “Indigenous seed benefit sharing.”

“Terminology is worthy of thoughtfulness, but, hopefully, [it] does not overshadow root concerns, which in this case includes the commercialization of seeds and the unsettled matter of what is adequate compensation for what to some are relatives, ancestors and children,” says Dr. Andrea Carter, AG outreach and education manager at Native Seeds/SEARCH, an Arizona-based seed conservation organization.

Recognition of prior ownership is a first step, but what about returning the seeds? Groups such as Native Seeds/SEARCH and the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance are working on drafting policies and beginning the work of returning Indigenous seeds to their native communities. They call the process “rematriation,” in recognition of the role women have played in seed stewardship. Returning seed breeding and stewardship to original Indigenous keepers on Indigenous land is an important step in seed sovereignty, which is in turn a foundational step in food sovereignty.

According to NAFSA (the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance, which houses the Indigenous Seed Keepers’ Network), “Seeds are a vibrant and vital foundation for food sovereignty and are the basis for a sustainable, healthy agriculture. We understand that seeds are our precious collective inheritance and it is our responsibility to care for the seeds as part of our responsibility to feed and nourish ourselves and future generations.”

“Rematriation of all Indigenously derived seeds is impractical,” acknowledges Kavanaya. It would mean no beans, corn or squash available on the commercial market. But recognizing this does not mean that all Indigenous seeds should be available commercially. Some nonprofits such as Native Seeds/SEARCH are removing culturally significant varieties from their catalog while choosing to leave others readily available.

Small seed companies provide a valuable service to all gardeners looking to benefit from careful breeding and stewardship, but seeds are not just food: they are also a living cultural legacy. Acknowledging this idea is just the first step toward addressing a complex issue. “It is a larger and much-needed conversation that requires the voices of many,” says Carter.

The post Payment for the Past: Recognizing Indigenous Seed Stewardship appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Meet the Forgotten Contributor to Sustainable Agriculture appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>That Bromfield was even on the farm in the first place was an unexpected chapter in a fascinating life. There was a time when Bromfield was mentioned in the same breath as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. In 1927, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his third novel, Early Autumn, about a woman keen to escape her Puritanical New England background. He also moved in Hollywood circles as a screenwriter. Born in Mansfield, OH in 1896, he studied agriculture at Cornell, before serving as a U.S. Army Ambulance Corps volunteer with the French infantry during World War I, and then moving to New York, where his career as a novelist took off. In 1925, he moved to France, joining the thriving expat literary community. For the next 13 years, he lived in France, while taking extended trips to India to learn more about local horticultural methods and to carry out research for several novels. Along the way—and several decades before Rachel Carson and her contemporaries birthed an environmental movement—Bromfield would aim to revitalize American agriculture in a way that was both profitable and sustainable.

His time in both France and India would influence his relationship with agriculture greatly. In France, he was struck by the importance of and devotion to preserving “terroir.” In India, he observed the large-scale use of composting to fertilize the soil. Meanwhile, in America, so much pre-industrial knowledge had been lost in the quest for industrial advancement. In chatting with other farmers and agricultural innovators, he saw how tools such as the moldboard plow intended to increase productivity but did so at the expense of the soil itself. He was convinced that successful farming entailed working with nature instead of fighting it.

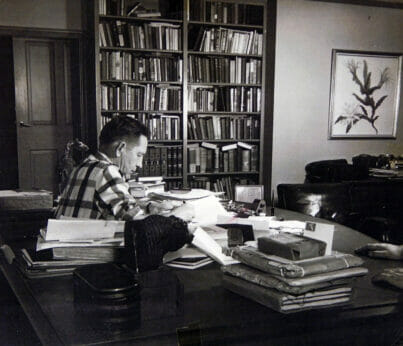

Louis Bromfield, courtesy of Malabar Farm.

In 1938, Bromfield, his wife and three daughters returned to Ohio. He had purchased several large tracts of farmland and harbored an idyllic dream of raising his children on a traditional American farm. He knew from his time in Europe that war was, once again, looming on the horizon. Bromfield felt it was vital to be self-sufficient and wanted the farm, which he named Malabar, to offer safety, food and shelter to his family and farm employees. However, what he saw was far from idyllic. That barren landscape, so devoid of life, was almost worthless.

Anneliese Abbot, author of Malabar Farm: Louis Bromfield, Friends of the Land, and the Rise of Sustainable Agriculture, notes that the US Department of Agriculture took the view that soil “is the one resource that cannot be used up.” The Dust Bowl was proving otherwise.

Bromfield set to work learning as much as he could about soil conservation. He was an early adopter of a new type of plow, created by Kentucky farmer Edward Faulkner. Faulkner was mocked for his claims that the widely used moldboard plow was damaging the soil by not allowing organic matter to decompose properly. Bromfield thought there might be something to his ideas, so he tried Faulkner’s redesigned plow, with excellent results. He became a vocal proponent of so-called “trash farming”—commonly known today as “no-till farming.” The method allows organic matter to decompose in the top layers of the soil, thereby replenishing nutrients and reducing the need for additional fertilizers. Bromfield remained ever mindful of the connection between soil health and human health. In his 1946 collection of essays, A Few Brass Tacks, he wrote, “As soils are depleted, human health, vitality, and intelligence go with them.”

Bromfield turned Malabar around, transforming it into a model of modern sustainable agriculture. In 1940, he wrote Pleasant Valley, detailing the steps he had taken to replenish the soil and the results of his work. On weekends, hundreds of people would flock to the Ohio farm to see Bromfield demonstrate the methods he endorsed. One such weekend in 1952, sponsored by Successful Farming magazine, saw thousands of visitors, with some reports listing as many as 10,000 people on the farm. Bromfield’s daughter Ellen later recalled it as an event she had no desire to repeat.

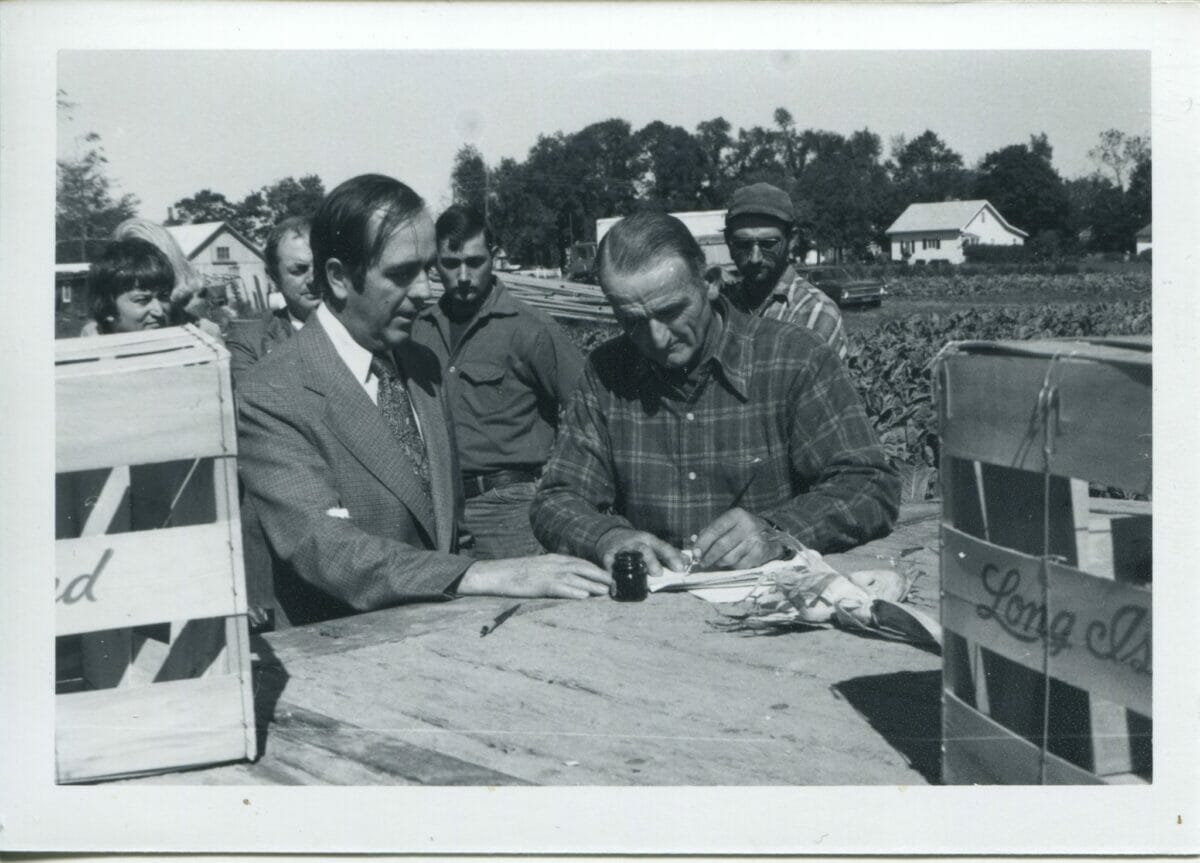

Louis Bromfield with farm visitors. Courtesy of Malabar Farm.

Louis Bromfield was recognized as an agricultural pioneer, but he did not work alone. He learned from fellow conservationists and organizations such as Friends of the Land. By turning Malabar into a showpiece for these “new” methods, Bromfield helped convince the nation that it was possible to feed both the soil and the people. At the same time, he remained a businessman, preaching that a farm could be both sustainable and profitable, as long as farmers learned to “work with Nature rather than fighting her.” Conservation, he argued, was good business.

In the mid-1950s, Bromfield began to draw up plans to create an ecological foundation at Malabar. Unfortunately, before that could become a reality, he passed away in 1956. Nevertheless, the Malabar Farm Foundation continues his educational work and Malabar is a national monument. Thomas Bachelder, a naturalist and president of the Malabar Farm Foundation, says that Bromfield’s greatest contribution to the sustainable agriculture movement and environmental stewardship was education. “Most of the innovative practices that he employed at Malabar Farm were already known and being applied elsewhere,” Bachelder says. “However, Bromfield was able to use his fame and gift for writing and speaking to get the message out much more effectively and to a much wider audience.”

Farmer and environmentalist Wendell Berry believes that good farming “is never the work of one individual, but the work of those living and dead.” With that in mind, Louis Bromfield is certainly part of an ongoing agricultural heritage that can only help to, in Berry’s words, “restore the richness of the country.”

The post Meet the Forgotten Contributor to Sustainable Agriculture appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post How to Better Support Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Indigenous communities are increasingly investing in agriculture to sustain their cultures and economies. Indigenous Peoples have a long history with agriculture—a history that wasn’t always recognized.

For much of the 20th century, scholars claimed that Indigenous farmers in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States (CANZUS) were marginal food producers who employed unsustainable farming practices, like slashing and burning, that led to environmental declines and their ultimate downfall.

These scholars argued that the “primitiveness” of Indigenous agriculture was reflected in the technologies they used. They posited that tools used by Indigenous Peoples, like the digging stick, were rudimentary compared to the more advanced plow cultivation used by European farmers.

We now know those claims are incorrect; Indigenous Peoples throughout CANZUS have long engaged in sophisticated forms of agriculture. By some estimates, Indigenous farmers out-produced European wheat farmers in the 17th and 18th centuries by a margin of three to five times per acre.

Despite Indigenous communities’ increasing desire to engage in large-scale commercial agriculture, there is still a lack of data about Indigenous engagement in the agriculture sector in CANZUS. This data is crucial to informing policies that set out to support Indigenous engagement and diversity in the agriculture sector.

Indigenous food sovereignty

Through the erasure of Indigenous agricultural histories, premised on the notion of terra nullius, CANZUS governments justified their appropriation of Indigenous lands and the territorial dispossession of Indigenous Peoples.

Latin for “land belonging to no one,” terra nullius was a legal term used in the Doctrine of Discovery to refer to land that was not occupied by the settlers or used according to their law and culture. Such land was considered “vacant” and available for colonization.

Yet in the face of governmental efforts to dismantle Indigenous agricultural economies, Indigenous Peoples have remained resilient and are making important strides toward food sovereignty through the revitalization of Indigenous food systems and cultural traditions.

Beyond food sovereignty, by reclaiming their agricultural roots, Indigenous Peoples are also alleviating food insecurity and contributing to economic development in their communities. As supporters of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, it’s important that CANZUS governments prioritize and support these Indigenous food sovereignty initiatives.

National databases are lacking

Although Indigenous Peoples have been participating in the agriculture sector since precolonial times, it hasn’t been until recently that contemporary agriculture has become a policy focus for Indigenous community development and well-being.

However, little knowledge exists about contemporary Indigenous agriculture in CANZUS because of the lack of comprehensive databases at the national level. National scale data collection tools that are currently available are still fairly new or non-existent.

1. Canada

In Canada, the Census of Agriculture does not allow farm and ranch producers to self-identify as Indigenous. However, data from the Census of Agriculture and the Census of Population provide some information about Indigenous engagement in agricultural activities.

Data from both censuses is linked using information which is common to both questionnaires such as name, sex, birth date and address of the operators. This information is used to create the Agriculture-Population linkage database, which provides useful information about Indigenous engagement in agriculture in Canada.

2. Australia

Australia does not maintain a national scale database on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (collectively referred to as Indigenous) production in the agriculture sector. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Agriculture Census also doesn’t allow farm and ranch producers to self-identify as Indigenous, which creates a significant data gap about Indigenous agricultural operations in Australia.

Despite this, there is still information available about the people employed in the industry, including those who identify as Indigenous, through the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Census of Population and Housing.

3. New Zealand

In New Zealand, information about Māori farms (the Māori are the Indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand, or Aotearoa in the Māori language), are compiled using the Agricultural Production Survey.

Māori farms are identified by matching the survey to three sources of data: Māori enterprises from the Māori authorities, self-identified Māori businesses from the business operations survey and a database held by Statistics New Zealand’s partner Poutama Trust. The matching process yields information about Māori engagement in agriculture, such as the number of agricultural operations, livestock and horticulture crops Māori farm operations have.

4. United States

In the US, a national scale data collection effort was piloted in 2002 in Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota to collect information about agricultural activity on American Indian reservations. Starting with the 2007 Census of Agriculture, this pilot project was expanded to include reservations across the US.

The Census of Agriculture in the US allows farm and ranch producers to self-report agricultural activity on American Indian reservations. If producers don’t respond to the mailed report, census employees—many who are tribal members that can bridge language or cultural barriers—follow up with them in person to help them completing their forms. The process yields an overview of agricultural activity on reservations in the US.

Better data is needed

The lack of baseline data on the scale and scope of Indigenous involvement in the agriculture sector continues to be an obstacle to effective engagement of Indigenous communities within the sector. This gap in data prevents governments and agri-food organizations from knowing what kinds of supports should be provided to reinvigorate Indigenous agricultural economies.

In order to better support the involvement of Indigenous Peoples in agriculture, more accurate data is needed. Being able to collect such data is crucial for developing a framework for Indigenous Peoples and communities that are interested in starting or expanding their engagement with the agriculture sector.

Omid Mirzaei is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Regina. David Natcher is a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of Saskatchewan.

The post How to Better Support Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Juneteenth Might Be the Most American Holiday of All appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>On Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people located in Confederate states. But although slavery was technically over, enslaved people in Texas weren’t notified that they were free until June 19, 1865—more than two years later. The reason for the delay is unknown, although there are some theories that the news was deliberately delayed in order to maintain the labor force. Another theory is that federal troops waited for slave owners to have one last cotton harvest before going to Texas.

After being freed, many African-Americans continued to work in agriculture, either as tenant farmers and sharecroppers or eventually purchasing their own land. Ultimately, millions of acres of land once owned by Black farmers were lost, often due to racism and discriminatory USDA policies. In 1920, there were nearly a million Black farmers, while today, only about 45,000 remain.

RELATED: How Did African-American Farmers Lose 90 Percent of Their Land?

In 1865, there were more than 250,000 enslaved Black people in Texas, and a year later, Juneteenth celebrations started popping up. As of 2021, Juneteenth is now considered a national holiday.

Over the years, the holiday spread throughout Texas and beyond, and celebrations grew to include rodeos, fairs and dramatic readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as Miss Juneteenth contests. Whatever the methods of celebrating, all of the events share one critical component: food.

And there were staple dishes that graced the tables each year, no matter where the festivities were held. As the Dallas Morning News aptly reported in 1933, “Watermelon, barbecue and red lemonade will be consumed in quantity.”

As more people learn about this seminal moment in American history, vibrant conversations about the foods centered around Juneteenth are happening as well, and Nicole Taylor’s new book, Watermelon and Red Birds, is the first Juneteenth cookbook to be published by a major publishing house. The James Beard Award-nominated food writer has also authored The Up South Cookbook and The Last O.G. Cookbook.

The title is derived from two foods important to the celebrations: Watermelon, which originated in northeast Africa and was brought over to America during the Middle Passage; and the red birds, which refer to a belief in the Black and Native American community that the birds are ancestors who have come back to share good luck. Taylor writes that the cookbook is a “declaration of independence” from traditional soul food and represents the freedom to create and evolve from a culinary perspective.

RELATED: Why Do We Eat Black-Eyed Peas on New Year’s?

Once Taylor nailed down the title, which came to her while riding on a train in New York City, the process of creating and testing the recipes in the cookbook happened relatively quickly. Most cookbooks can take between two and three years to pull together, but it took Taylor only about 18 months. “I had a massive spreadsheet of fruits and vegetables that are summer, along with [a spreadsheet] that historically are connected to Juneteenth and summertime,” she says. “I’ve been writing about Black food and culture for a moment, and the recipes needed to be rooted in the Black table.”

Although there aren’t recipes for Black celebration foods such as macaroni and cheese or sweet potato pies, Taylor has taken ingredients that are traditionally part of the Black experience, developing creative and innovative dishes with them. For example, a sweet potato spritz, yellow squash and cheddar biscuits and watermelon kebabs with citrus verbena salt are familiar yet unexpected.

“For Black Americans who have been celebrating [Juneteenth], they will look at this cookbook and it will bring back memories of celebrations in the backyard, or getting in a long line to get fried fish or fried shrimp or a turkey leg, and it will get them excited and create these things at home. And also try something new to add to their Juneteenth table, and talk to their family about who made the potato salad,” says Taylor. “For those celebrating for the first time…I hope they walk away understanding that it was a holiday born in Texas, and because of the Great Migration, you find it in backyards in Oakland, in Chicago, in Brooklyn. And those same folks will get inspired to get in the kitchen and cook. Food is a great way to have conversations.”

The post Juneteenth Might Be the Most American Holiday of All appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Past, Present and Future of the West’s Water Woes appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>This particular policy will have an exceedingly small effect on the overall water situation in the West, and in the Southwest in particular. To know why, and to know what might actually work, we have to know how we got to this point.

A Brief History of Water in the West

In the early- to mid-19th century, much of the American West, from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, was referred to as the Great American Desert. This was a little bit derisive, from the Easterners, but large swathes of the American West are either literal desert (both hot and cold: “Desert” refers to precipitation, not temperature), semi-desert or simply very arid.

Throughout the known history of the American Southwest in particular, there are comparatively few large-scale pre-Columbian settlements, for the very basic reason that this area is not naturally well suited for such. This is not, of course, to say that people didn’t live here; the communities just tended to be smaller and/or nomadic, at least inland. There are exceptions, though.

The coastal peoples of Southern California, including the Tongva and Chumash, were sedentary due in large part to the availability of seafood; they did not practice much or any agriculture, as it was neither necessary nor sensible in the environment. The Hohokam crafted wildly complex irrigation to create a home in what is now Phoenix, Arizona; some of their canals, a thousand years old, were paved with concrete and are still in use today. The Hohokam culture fizzled out and dispersed, probably, just a few decades before Columbus’s arrival, owing (also probably) to climate change that made the Phoenix area incompatible with life. The Ancestral Pueblans, who lived in parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, experienced a boom time for their cities, which turned out to be a cycle of wet weather. The climate changed; the Ancestral Puebloan people moved to somewhere wetter.

Barren landscape in Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo by Sean Pavone, Shutterstock.

The American West, excepting the Pacific Northwest, has a very bad combination of precipitation factors for sustaining human life. The first is simply that it doesn’t rain very much; Los Angeles receives, averaged over the past 100 years, somewhere just north of 14 inches of rain per year. New York City gets between 40 and 50 inches per year. Phoenix gets less than 10.

The other big problem is that, unlike in the East and Midwest, which have reasonably consistent rain (or snow) regardless of month, the West experiences long periods of absolutely zero rain, followed by a few weeks of rain that can be incredibly intense. So, even those annual precipitation numbers are misleading for, say, agriculture, which needs consistent water. It also means that the West is very prone to extreme floods, as waterways that lie dry for 10 months suddenly get the equivalent of the Mississippi River’s cubic-feet-per-second (CFS) flow all at once.

From Colorado to southern California, Oklahoma to North Dakota, people have always lived in the West. But very rarely have they lived in one dense place without moving around, and the few times that has happened have not ended well.

Westward Migration and Consequential Irrigation

The modern history of the West starts, really, with the Mormons, who were repeatedly kicked westward until they landed in Utah, which no other white people seem to have wanted. The Mormons turned out to be excellent at irrigation, first damming a small stream in what’s now Salt Lake City called City Creek, in 1847. By the turn of the century, the federal government had decided that the West could be tamed and made to provide in ways it never really had before. In 1902, Congress passed the Reclamation Act, which was designed to turn inhospitable and economically ignored parts of the United States into profitable members of the Union. Basically, the idea was that the government would sell lots of land in the West, and use that money to pay for irrigation projects in the West, which would make the West a nicer place to live, which would entice more people to live in the West.

This, along with some historically wet years in the 1880s that caused the deserts to bloom, worked. (There was a popular, despite being quickly debunked, theory called “rain follows the plow” that posited that if you tried farming desert land, it would rain. It was sort of “if you build it, they will come,” but really, really wrong.) Huge populations flowed out of the east, south and midwest into lands formerly thought of as uninhabitable, enticed by cheap land and free water. That’s right, the water would be heavily subsidized by the government, in an effort to better tempt farmers. (We’ll revisit this later.)

Out of the Reclamation Act, the Bureau of Reclamation was formed to do all this irrigation building, and its major weapon was the dam. It dammed everything that could conceivably be dammed and plenty of things that shouldn’t have been. This obviously had untold destructive effects on the environment, but it created economies out of whole cloth. Many of these economies, including farming in the desert, were shortsighted, unsustainable and very expensive.

An abandoned house in Kansas, 1941, after the Dust Bowl. Photo courtesy of the Everett Collection.

When the Colorado River was dammed repeatedly, the Mountain states demanded that, to approve huge and pricey projects such as the Hoover Dam, they’d need to get water for themselves. So they got water rights, but most of Colorado is too high in elevation, too cold and too dry to make sense for farming. It happened anyway, and Colorado (along with the Dakotas) became major producers of…cotton and alfalfa. There was already a surplus of these crops, so it made no macro-economic sense, and cotton in particular is a very thirsty crop, so it made no geographic sense. But it made micro-economic sense, in that you could move to Colorado, get cheap land and free water to grow whatever you could. To help prop you up, the government would guarantee prices for your crops. On an individual level, great. On any kind of broad scope, pure folly. This led to the Dust Bowl: inexperienced farmers using wild amounts of free imported water on land that couldn’t handle it. Eventually, it turned to dust, and farmers turned further to the West.

Who Has the Right to Water?

In California, the Central Valley was once, as Marc Reisner writes in his seminal book Cadillac Desert, a sort of Serengeti of North America: a massive grassland ecosystem in inland California, seasonal marsh in the north and desert grasslands in the south, home to millions of birds, mountain lions, wolves, bears and more. It has been almost entirely destroyed and is now the most valuable agricultural land in the country.

The Bureau of Reclamation dammed every possible river to move water to southern and inland California. The Central Valley Project arose during the New Deal to move water from Northern California, especially the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, to the Central Valley. Farmers and engineers also discovered a massive aquifer underneath the Central Valley, the remnants of an ancient sea. They started to drain it at extraordinary rates, and the aquifer was not refilled, because the water that might have, eventually, refilled it was also being rerouted to farms.

The Shasta Dam, one of the first major facilities built for the Central Valley Project. Photo by Wirestock Creators, Shutterstock.

The federal government has also issued gigantic subsidies to farmers in the Central Valley, in the form of incredibly cheap water and in crop subsidies. This has enabled the Central Valley to grow confusing crops for a desert environment, including almonds, citrus, avocados, pistachios and stone fruits, all of which need a lot of water. Farmers never needed to try to work with the landscape; they could overpower it through brute force and lots of federal cash.

Another major issue is the eager sloppiness, and sometimes, illegality, of the water rights systems.

Originally, subsidized water was only supposed to be available to individual holdings of 160 acres, which was believed to be plenty to make a living in California. Farmers quickly blew past that, and enforcement was basically abandoned. That led to mass consolidation, with a prime example being the Westlands Water District, in which a few hundred incredibly rich farmers spend hundreds of thousands of dollars lobbying to receive vast amounts of cheap, imported water to run wildly profitable farms in the desert.

RELATED: California Wants to Pay Farmers to Not Farm This Year

Those in charge of allocating the water also, almost right from the beginning of these projects, have overestimated the amount of water that’s actually available. “The water agencies have promised, sometimes, five times more water than exists in California in contracts and with water rights claims,” says Carolee Krieger, executive director of the California Water Impact Network, or C-WIN, a non-profit advocacy group that fights for the sustainable use of California’s water. “We call this paper water.” Sometimes, a project will pass, with states signing off, based on an estimate that’s way off, or that becomes way off due to the realities of construction. Over-promised water leads those with water rights to take far more than they should, leaving less for everyone else and destroying ecosystems in the process.

California’s Central Valley is the most extreme example, but there are agricultural operations all over the West that arose from the same zeal. Legislators and bureaucrats from, or obsessed with, Western states demanded water rights in order to pass water reclamation projects, and then demanded federal aid to keep the operations running on redirected water viable.

The Central Arizona Project delivers water from the Colorado River to Tucson and Phoenix, and also to farmland in surrounding counties. The Columbia Basin Project delivers water from the Columbia River hundreds of feet over mountains to feed into Grand Coulee Dam, to feed farms in eastern Washington state. There are dozens of these projects, some of which benefited (albeit greatly) just a few farmers.

An Uncertain Future

In Los Angeles, the water restrictions have attracted criticism, and likely will meet with non-compliance. Some of the reasoning for this criticism is absolutely valid. About 80 percent of California’s water is used to irrigate the desert and grow water-intensive crops, while only about 10 percent goes to municipal use. (The remainder is used by industry.) Lawns in Los Angeles are bad for the environment, but they are not the reason why Southern California is running out of water.

The western states have repeatedly and continuously neglected to take action which could allow for the sensible use of water. Los Angeles has truly awful stormwater catchment systems, for example. Billions of gallons of water in Los Angeles County flow into the Pacific Ocean every year, picking up all kinds of pollution on the way. Programs to fix this problem have been proposed, passed, and then lapsed into bureaucratic stasis where nothing actually gets done.

Fields of drought. Photo by Nature1000, Shutterstock.

There’s also the not insignificant problem of evaporation. Most of the reservoirs and canals in the West are open-air, due to cost or earthquake issues. But they’re also in the desert. Millions of acre-feet of water (the amount of water needed to cover one acre with one foot of water) evaporate each year.

In essence, how we got to this point is due to a few different key factors. One is climate change; this has happened before, which isn’t to take anything away from its anthropogenic causes or severity this time around. The West is hotter and drier each year. Another is the rampant cash grab of water over the past 10 years: All the available sources of water, be they the Colorado River, the Tulare Aquifer underneath the Central Valley, or the Owens River (which was stolen by Los Angeles, as depicted, a little loosely, in the movie Chinatown), have been dammed, directed and drained beyond all possibility of sustainability. Federal funding provided unlimited cheap water, power, and land, which was and continues to be used recklessly.

I asked Krieger what happens if the Central Valley groundwater, which farmers are now pumping relentlessly to make up for the lack of subsidized water coming from the Colorado River projects, just…dries up. “Well, that’s what we’re all about to find out,” she said. We’re about to find out a lot of things.”

The post The Past, Present and Future of the West’s Water Woes appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Lasting Legacy of the First Farmland Preservation Program appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The densely populated, 118-mile-long island, which stretches east from New York City to the outer reaches of Greenport and Montauk, was once home to an agrarian lifestyle. Then, in 1947, 4,000 acres of potato farms in Nassau County were converted into what would be known as the country’s first suburban community: Levittown. That planned community would also herald the island’s suburban sprawl, making way for other like-minded ideas. By the late 1960s, Long Island looked a lot less like farmland and a lot more like an extension of the city.

Long Island was becoming less agrarian, and then-county executive John Klein realized that this decimation of land was going to become a problem. In 1974, with his help, the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program was launched in an attempt to curb the sprawl. It was among the first programs of its kind in the nation to protect working farms.

“The county would buy the development rights to farmland and leave the residual land itself still in private ownership from the farmers,” says Robert Carpenter, director at Long Island Farm Bureau.

The program, Carpenter says, offered the farmers a financial incentive while keeping the land in their hands. Meanwhile, farmers would continue to pay taxes on the land and continue to maintain it, which simultaneously benefitted the government. “It was really a win-win situation at that point for both the government and the farm community,” says Carpenter.

In 1977, George C. Reeve, seventh-generation farmer and owner of Reeve’s Farm, gave up development rights to his 84-acre farm, which is still in operation today.

The result, according to records kept by the Suffolk County Farmland Development Rights Program, has been a total of 11,000 acres of protected farmland within the county since the program’s inception and more than 20,000 acres of protected farmland within the county through the combination of additional county, town and other preservation programs.

“I think that if there was no farmland preservation program, or no open space program, we would see, basically, you know, Babylon, Islip, Huntington, develop like that, all the way out to the East End, for certain,” Carpenter says, comparing Long Island’s North and South Forks to the highly developed areas of Nassau and western Suffolk counties.

In this fundamental way, he says, the program has been a success, and, to some degree, a benchmark for other programs around the country. Connecticut’s statewide and voluntary Farmland Preservation Program, for instance—developed four years after Suffolk County launched its program—has preserved 45,000 acres of land and seeks to preserve 130,000 acres in the long term. New Jersey’s Farmland Preservation Program was also established in the early 1980s, helping to save some 69,500 acres of farmland by 2000.

RELATED: Study Finds 1 Percent of Farms Own 70 Percent of World’s Farmland

The need for such programs is still felt today. According to a 2020 report from American Farmland Trust, 11 million acres of American agricultural land was lost to development between 2001 and 2016.

Perhaps the reason for the Suffolk program’s success, Carpenter and others say, is that it has targeted a group of landowners who have been the most likely to take advantage of it. “Most farmers, their largest asset by far is the farm itself,” says Kareem Massoud, winemaker at Palmer Vineyards and Paumanok Vineyards on the North Fork of Long Island and president of Long Island Wine Country. “And most farmers are stuck with a situation where the crops that they grow are not that profitable and Mother Nature is your partner.” That twinned relationship makes farmers vulnerable, says Massoud, and it also makes them susceptible to appeals from developers, because the work is hard and the reward is often small.

Another reason the program worked—and has continued to work—says Massoud, is that the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program has relied on the market to dictate land value. “Farmers aren’t stupid. They’re business people, too,” he says. “And, after all, for most farmers, this is their life savings, essentially, tied up in the land, and, so, in order to make it work, you have to pay fair market value.” When farmers cede development rights to the county, they do so at a rate that competes with a real rate that they might get from an actual developer and that, says Massoud, does make an appreciable difference when it comes to incentivizing preservation.

For farmers entering the business, properties that have already sold off development rights may also prove more attractive. “If your true purpose is to farm, with no consideration to future generations and what their desires might be, purchasing property or even leasing property to grow that has no development rights intact is very affordable,” says Christine Tobin, owner of Mattebella Vineyards in Southold, New York.

Tobin, who owns 21½ acres with her husband Mark, says that the majority of their property—all but three acres—lacks development rights and, as a result, has reduced property taxes. “The real estate tax on that component of such a large piece of property is under $1,000 a year,” she says.

But the true legacy of the Suffolk County Farmland Preservation Program has been less—less sprawl and fewer houses on eastern Long Island, where wineries and farmland continue to populate the landscape. If the standard home on the East End is built on an acre of land and the Preservation Program lays claim to 11,000 acres of protected land, one can imagine 11,000 homes in its place, where vineyards, cornfields and apple orchards still have room to grow.

The post The Lasting Legacy of the First Farmland Preservation Program appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Study Finds Black Farmers Have Lost $326 Billion in Land appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>But there are many other numbers involved here. A new study, led by Dania Francis of the University of Massachusetts Boston, analyzed USDA data to attempt to figure out the monetary value lost as a result of, largely, racist institutions and weird legal obstacles.

Francis looked into USDA census data ranging from 1922 to 1997, aiming to find, according to Reuters, the present-day value of all the acreage of land that was lost. The figure she arrived at is $326 billion, but even that, Francis acknowledges, is a very conservative estimate of even merely the monetary damage done to these Black farmers.

RELATED: The CSA’s Roots in Black History

In an article for the New Republic, Francis and co-authors note that the value of the lost farmland doesn’t account for the fact that farmland is, as Bill Gates well knows, an incredibly good investment. “Developers have turned some of this land, like in Hilton Head, South Carolina, into incredibly expensive residential and commercial properties,” they write.

The current USDA, run by Tom Vilsack, has at least acknowledged the USDA’s centuries-long history of discrimination against Black farmers, although attempts to actually right the wrongs of the past have not been especially successful, with payments stalled owing to lawsuits from right-wing groups.

The post Study Finds Black Farmers Have Lost $326 Billion in Land appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>