A team at Western Illinois University, bolstered by a first-of-its-kind initiative, is helping towns across the state democratize their food economy.

This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Until recently, if you drove down the main street in Cairo, Illinois, a majority Black community at the southernmost point of the state, you wouldn’t have been able to find a grocery store.

Like many once-booming Mississippi River towns, Cairo’s vanished grocery stores have been part of a harrowing trend of decline.

For decades, Cairo—wedged between the Missouri and Kentucky border at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers—has struggled to grow its local economy and population. One hundred years ago, Cairo boasted more than 15,000 citizens; today, its population has shrunk below 1,700. Median household income hovers just above $30,000, with about 24 percent of residents living in poverty—more than double the average in Illinois. Cairo doesn’t even have a gas station. Town residents have felt its lack of a grocery store more acutely, often having to cross state lines to get the most basic supplies.

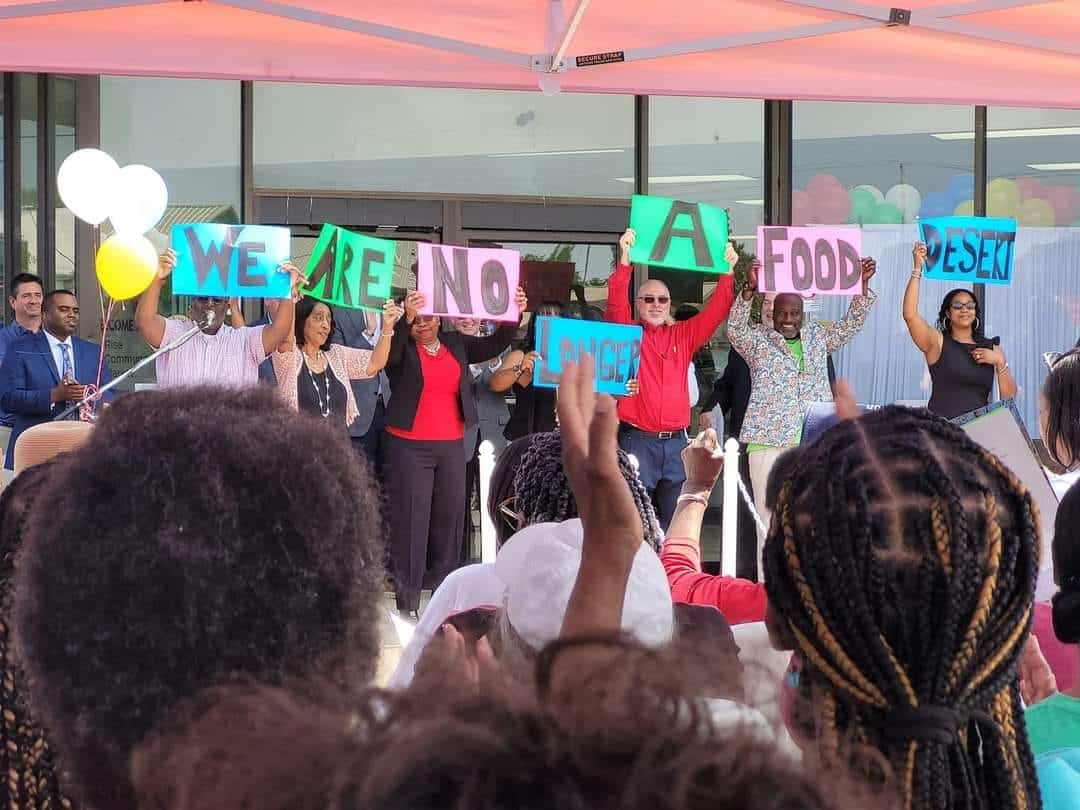

But recently that trend has begun to change. Last summer, Rise Community Market opened its doors in Cairo, marking the first time in more than eight years town residents could go to a local grocery store. It was the result of more than two years of hard work and planning by community organizers, city officials and public service agencies. One reason behind their success: the grocery store’s model.

In 2021, Illinois Lieutenant Governor Juliana Stratton connected Cairo Mayor Thomas Simpson with a team at Western Illinois University about opening a community-owned cooperative grocery store right off Cairo’s main street. Sean Park is the program manager of the Value-Added Sustainable Development Center (VASDC), a unit of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs at Western Illinois University in Macomb. “That particular area had been beat down so much,” says Park, who has more than a decade of experience owning and operating an independent grocery store, as well as a background in rural development. Working with the Institute, Park has found unlikely success in rejuvenating small town businesses like grocery stores in a time when they face persistent distress.

Cairo’s situation may be unique, but it’s not unusual in losing its grocery store. Limited or no access to food tends to be thought of as an urban phenomenon, but it affects rural communities just as much. Seventy-six counties nationwide don’t have a single grocery store—and 34 of those counties are in the Midwest and Great Plains. According to a 2021 Illinois Department of Public Health report and the US Department of Agriculture’s Food Access Research Atlas, 3.3 million Illinois residents live in food deserts. (The USDA defines a rural food desert as any low-income community where the nearest grocery store is 10 or more miles away). To combat this growing reality, in August 2023, Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D) signed into law the Illinois Grocery Initiative, a first-of-its-kind $20 million program that will provide capital, technical assistance and a range of services to open or expand grocery stores in underserved and low-income neighborhoods across the state.

Even before Illinois’ new initiative, rural and small town communities in Illinois like Mount Pulaski, Farmer City and Carlinville have been working with VASDC, organizing their communities to pave the way for cooperatively owned, community-based grocers. Cooperative grocery stores were once perceived as the stuff of elite, granola-munching college towns and coastal enclaves. But today’s co-op advocates emphasize the power of cooperative ownership structures to provide local, democratic control of a community’s essential needs. While the economies of mass-scale production and logistics that sustain and supply traditional chain store or conglomerate grocers like Walmart and Dollar General are often deemed “efficient,” the Covid-19 pandemic revealed their underlying fragility and susceptibility to supply chain disruption.

It’s estimated that Walmart now sells just over a quarter of all groceries in the United States. In his forthcoming book Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, antitrust expert Austin Frerick writes that the gutting of New Deal-era price floor regulations has allowed companies like Walmart to amass a level of dominance not seen in US history. To do so, he writes, Walmart “demands that a supplier decrease the price or improve the quality of an item each year,” in addition to giving Walmart delivery priority.

In contrast, local, cooperative ownership helps guarantee that decision making about how a store is run and what it stocks are based on the community benefit. The items on the shelves of co-ops like Cairo’s Rise Community Market aren’t the stuff of Whole Foods, but these stores help bring needed items close to the community, like fresh produce and meat, which tend to be sourced from farmers and producers nearby. Robert Edwards, Rise Community Market’s store manager, says that local stores may not be able to match the extensive inventory and cost a little more than the Walmarts of the world, but “what you get for those few extra cents you spend is the ability to help those in your community” by ensuring that goods are available “for those in your community who lack the ability to travel for them.”

Illinois Lieutenant Governor Juliana Stratton, center, cuts the ribbon at Rise Community Market’s opening ceremony.

Interest in bringing community-owned stores to rural America isn’t limited to Illinois. Across the country, communities are experimenting with new ways to address the disappearance of rural and small town grocery stores. The Institute for Self-Reliance has detailed examples of innovative models in Pennsylvania and North Dakota, including self-service grocers, rural grocery delivery and nonprofit grocers. Food cooperative programs are now active at state universities in Kansas, Nebraska, Wisconsin and elsewhere, and in recent years rural cooperative development centers have been active in almost all 50 states.

“Cooperative development is once again ascendant,” says Stacey Sutton, director of the Solidarity Economy Research, Policy and Law Project and associate professor in the Department of Urban Planning and Policy at the University of Illinois Chicago. “And it’s rising in areas that have not seen sufficient support in the past.”

Even though agricultural cooperatives, or farmers’ co-ops, have long been a cornerstone in rural communities, Sutton explains that there has been a significant gap in cooperative development for other types of collectively owned, democratically managed enterprises. Part of this is due to the influence of institutions like the USDA and land grant universities in rural communities, which have traditionally invested their resources in agricultural cooperatives, pooling resources around commodity crop and livestock production. “What’s missing is exactly what’s happening at Western Illinois, in terms of supporting other types of cooperatives, such as food cooperatives, which are essential in disinvested communities,” says Sutton.

One of the major challenges facing cooperative development in rural communities is access to technical services, or the process of providing specialized know-how and business acumen to help communities plan and build capacity for creating models of collective ownership. This is where the VASDC team comes in.

Unlike chain grocers or corporate juggernauts that take a one-size-fits-all approach, VASDC’s methods are more artisanal, tailored to the specific needs of developing a sustainable community-owned grocer. “The financial calculations of a full business plan require everything down to the floor plan,” Park says. “If we change the floor plan and some of the refrigeration section, it’s going to change your utility bill and the amount that you sell in each department. From there it’s going to change the profit margin in both those departments.”

Facing stiff competition discount stores like Walmart means that a cooperative’s success is totally dependent on community buy-in and organizing. For many communities, there’s an educational component to VASDC’s consulting. The kind of ongoing, sustainable collective action and community organizing required to keep a cooperative vibrant, coupled with learning and navigating the practice of democratic ownership, can be taxing and messy. Cooperatives often require more than just showing up to vote. It can take anywhere from six months to seven years to build a cooperative grocery, and it may not always work the first time.

Park says it can also be a hurdle to inform residents that cooperative grocers are open to non-members for shopping and that member-ownership is more about investing in a store’s sustainability than earning Costco-like membership privileges. On the flip side, member-owners who are unfamiliar with cooperative concepts sometimes expect Gordon Gecko-like returns on their investment. That’s just not possible in an industry where profits can be razor thin or in a cooperative where profits are typically reinvested in the store. Yet, Park says that for the communities he serves, the process is often worth it. “When you can guide them from concept to that opening day, that’s really rewarding.”

In the 12 years that Park has led VASDC, he has helped countless rural communities throughout Illinois and the Midwest develop community ownership models for grocery stores. Edwards, the manager of the Cairo co-op, credits Park’s successes to his previous work owning and managing a grocery store. “I find solace in knowing that he understands the hurdles of managerial responsibilities and the stress this can bring.” Park’s advice, he says, has been “invaluable in helping me navigate challenges,” and was vital to him in making a smooth transition into the manager role when he started in January 2023, six months before the opening. “Sean is unafraid of telling you when you’re making a mistake or that an idea is ridiculous,” Edwards says, “Knowing that you have a partner like that instills trust and that makes it easier to turn to him when you find yourself in doubt.”

This coming year will be the first of what Park describes as the “2.0” version of the center, with the addition of new staff members timed to address the expected interest generated by the Illinois Grocery Initiative. The additional staff will increase the center’s capacity to provide holistic solutions to tackle the challenges that affect grocers, small producers and growers, and rural communities across the state.

Given the demands on their time, the center’s staff is pragmatic. Kristin Terry, one of the center’s recent hires, who previously worked in economic development for Macomb, Illinois, says that if you’re within 10 or 15 miles of a Walmart or the new iteration of dollar stores that sell groceries, a community cooperative will not be viable, because too many people will still opt for the superstore. In this respect, it’s a Walmart economy, Terry says, and residents are stuck living in it.

While the speed with which Rise Community Market developed is a testament to Park’s work and the efforts of community organizers, the cooperative has faced some setbacks. A set of brand-new cooler cases malfunctioned and a walk-in cooler broke down overnight, leading to product loss and a decline in revenue. However, a USDA grant in combination with community backing and a GoFundMe campaign have helped address such setbacks.

“Fortunately, we have a community that believes in this project and wants to support the store regardless of the struggles we’ve faced,” Edwards says. As volunteer and community-owner support continue to grow, Edwards and the co-op members are optimistic that their store will be able to meet its fundraising and revenue goals. “The most important part of building a community-owned store is getting long-term community buy-in. It doesn’t end with the grand opening,” Edwards says. “You have to be committed to a long-term project.”

That appears to be true on the consulting side, as well. Recently, Park and the VASDC team held a meeting in a community that Park had visited a few years ago and had only found one person interested in the idea of building a cooperative grocer. This time, they found 10.