The post This Farmworker Collective is Organizing For ‘Milk With Dignity’ and More appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>He was excited to begin a promising new life in America, with opportunities and comforts he could never have imagined back home. But this fantasy was quickly shattered by the harsh reality of dairy farming.

“When I got there, I saw that I was going to be living in an old trailer all by myself,” he says. “No cellphone service. No internet. Just totally alone and isolated. That was my first shock.”

When Balcazar began work a few days later, he didn’t know how to do the job and didn’t understand the language. But he immediately began putting in long hours, seven days a week.

He was excited when pay day came around and he got his first check. “When I opened it, my heart sank. I was only getting paid $3 to $4 an hour,” he says. “For the work I was doing and as hard as I was working, it was much less than I expected.”

Balcazar approached the farm manager, who told him, “it is what it is,” and if he stuck around, he might eventually get a raise.

Months passed, but the raise never came.

Vermont’s dairy industry relies heavily on the labor of undocumented migrant farmworkers. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Balcazar’s story is typical for undocumented migrant farmworkers in Vermont, who now comprise the overwhelming majority of dairy workers in the state.

Dairy farms in the region are under immense pressure to cut costs due to industry consolidation and globalization, which allows powerful agribusinesses to place downward pressure on farmers’ incomes. Farmers then hire migrant workers who they can pay far below minimum wage.

The visa program and federal law designed to protect seasonal migrant workers, such as agricultural workers in California, for example, don’t apply to dairy farmworkers in Vermont because of the year-round nature of dairy production.

As a result, the majority of these workers face dangerous work conditions and live in substandard housing. Despite paying taxes, they do not have the rights of US citizens and are under constant threat of deportation by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol.

Migrant Justice, a Vermont-based farmworker-led organization, was founded in 2010 in response to the death of José Obeth Santiz Cruz, a 20-year-old migrant worker from Chiapas killed in a tragic workplace accident, and the rampant exploitation taking place on most dairy farms.

Its signature program is Milk with Dignity, which enlists powerful corporations to pay a premium to help raise wages and improve conditions on supplier farms. Compliance is monitored by an independent third-party organization.

Will Lambek, an activist with Migrant Justice, says that one of the reasons that dairy workers created this program is because of the state’s failure to address labor and housing violations.

“The structure set up through the Department of Labor and the Department of Health have left farmworkers out and haven’t protected their rights,” he says. “So, that’s why dairy workers created their own model … to ensure dignified treatment for their workers.”

Rubinay Montero, a Migrant Justice leader, marches through Middlebury, Vermont in December 2022. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

When Balcazar was just seven years old, his father moved to Vermont to work on a dairy farm. He would send money back to Mexico to support his family, but the money wasn’t enough, so in 2011, when Enrique was 17, he followed his father to the United States.

As a child of farmworkers, getting a visa wasn’t an option, so he decided to risk his life crossing the border. It was a significant risk, but it was his best chance to earn enough money to continue his education in Mexico.

That’s how he became one of the millions of mostly black and brown migrants and refugees escaping unstable governments and economic crises caused in part by centuries of imperialism, exploitation and deliberate underdevelopment. Many arrive in the U.S. to take jobs that offer low wages and no benefits, that would otherwise remain unfilled and that are essential to the US economy.

After a couple of months working on that Vermont farm without a raise, Balcazar found a new position on the farm where his father worked. It was there that two members of Migrant Justice visited him and invited him to a community assembly. That visit would change everything for Balcazar.

When he showed up at the assembly, he felt a strong sense of community because there was a room full of farmworkers, just like him, talking about the same injustices that he had experienced. It was the first time he realized that his experience wasn’t an isolated incident; the problems his community was facing were systemic.

“For decades, the migrant community has been criminalized and persecuted by a system that wants our labor but doesn’t care about our lives,” says Balcazar.

At that moment, he thought about his parents and everything they had gone through. “It left a mark on me and I had a realization of the challenges and the solution: organizing for our human rights,” he says.

Although Balzcazar was working 60-70 hours a week without a day off, he became increasingly involved in Migrant Justice. At the time, it was starting to organize for freedom of movement, allowing migrant workers access to driver’s licenses. “That was really exciting for me because I saw that people were working together based on those common experiences,” says Balacazar. “And so, right there, I was hooked.”

Enrique Balcazar leads a protest at a Hannaford Supermarket in April 2023. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Balcazar has since emerged as one of Migrant Justice’s most visible and vocal leaders. His activism has helped to improve not only his own work and living conditions but those of hundreds of migrant dairy farm workers in Vermont.

After two years of advocacy, Migrant Justice was instrumental in passing a law allowing migrant workers to get driver’s licenses, which has changed farmworkers’ lives in rural Vermont.

Balcazer also became a part of developing the Milk with Dignity program and the campaign to enlist Ben & Jerry’s, which is based in Vermont and is the largest ice cream company in the US with 2022 sales of $910.68 million.

In 2014, Migrant Justice began pressuring the company with protests in front of Ben & Jerry’s stores, picketing its board meetings and marches.

One day, they marched 13 miles to their ice cream factory. “Imagine working 12 hours on a farm, before spending the whole day walking under the sun and going right back to another shift. Those were the sacrifices that we made to defend their dignity,” says Balcazar.

It was during this time that Balcazar and other community leaders were detained by ICE. Eventually, thanks to mobilization from the community, Balcazar was freed.

“That was a really difficult experience, but having gone through it, I want to say this deepened my commitment even more to continue fighting for justice and human rights for my community,” he says.

Migrant Justice eventually won a contract with Ben & Jerry’s in 2017, which covers 100 percent of Ben & Jerry’s northeast dairy supply chain and 20 percent of Vermont’s dairy industry. This has changed the lives of more than 200 farmworkers. Migrant Justice reports that, since the agreement, $3.4 million has been invested in workers’ wages and bonuses and dramatically improving labor and housing conditions. The goal is to expand the program to cover every farm in Vermont and nationwide.

Farmworkers picket in front of the corporate headquarters of Hannaford Supermarket in Scarborough, Maine in February 2023. (Photo courtesy of Migrant Justice)

Now, Migrant Justice is trying to enlist Hannaford Supermarket to the Milk with Dignity program. Hannaford is headquartered in Maine, with nearly 200 shops all over New England and New York. It’s one of the largest supermarket chains in the Northeast and a significant buyer of dairy products in the Northeast.

“Hannaford has had a number of responses over the course of the campaign and has consistently rejected calls to sit down with dairy workers in their supply chain,” says Lambek.

Hannaford is a subsidiary of the Dutch agribusiness giant Ahold Delhaize, which reported $91.51 billion in sales in 2022. Both companies claim to be committed to respecting human rights.

However, Migrant Justice alleges that labor and housing rights violations are taking place on supplier farms for Hannaford supermarkets. Hannaford has said it has investigated those allegations and that none have been substantiated.

After facing pressure from the public, one of Hannaford’s responses has been to set up its own hotline, called the “Speak Up” line. Workers in its supply chains can submit a complaint if their rights are being violated. When it made the announcement last year, workers decided to take the company up on it.

“Workers on 10 farms submitted complaints, and, through their experience, have shown that this company line is a farce,” says Lambek. “It hasn’t protected any worker’s rights and hasn’t provided any remedy for workers who have been abused.”

Most recently, in June of this year, Hannaford released a statement saying, “Because of the complexity and scope of the issues facing migrant farmworkers, we do not feel this approach is scalable. Nor do we feel that these issues can be solved with a patchwork of loosely affiliated programs like Milk with Dignity working independently.”

Research supports the effectiveness of Milk with Dignity’s approach. Milk with Dignity is an example of a worker-driven social responsibility program (WSR) that is designed and led by farmworkers. It was modeled after the Coalition of Immokalee Workers Fair Food Program and has been shown by a 10year longitudinal study to be “the most effective framework for protecting human rights in corporate supply chains.” Earlier this year, Harvard Law School published a report calling WSR “a new, proven model for defining, claiming, and protecting workers’ human rights.”

Farmworkers pose outside their farm, a participant in the Milk with Dignity Program. Efrain (R) reflects: “Before you just had to do what they told you. No holidays, no sick days, no vacation, no bonuses, no raises. Before we didn’t have protections. Now we do. We feel more dignified.”

Balcazar can attest to how much migrant workers’ lives improve once their employers join WSR programs such as Milk with Dignity. When he reflects on his arrival in Vermont 12 years ago, the change has been drastic.

“Now, you can drive to the store without fear, you can take your family out to a park and, if you’re working on a farm, then, when you’re working, you have dignified conditions that you deserve,” says Balcazar.

Balcazar and his community envision a future where their Milk with Dignity program expands to cover every farm. Public awareness and support can help them achieve this goal.

“The next time that you drink a glass of milk or eat that pint of ice cream,” he says, “remember: the cows don’t milk themselves.”

The post This Farmworker Collective is Organizing For ‘Milk With Dignity’ and More appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Farmers Market, Delivered appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Jackie and Donald Bickel inherited their dairy farm from Donald’s father, and they were raising their own kids in the dairy life. But, by 2018, Jackie and Donald were starting to talk about finding a way out. The Bickels sold their milk to a co-op and, economically, it wasn’t proving feasible.

“In 2018, milk prices were equivalent to what my father-in-law was receiving in the 1980s,” says Jackie Bickel.

And they weren’t the only ones—many nearby dairy farms in Ohio had closed up shop over the previous years after struggling against low prices.

Fortunately, the Bickels’ daughter, Maggie, had an idea. As part of a Future Farmers of America (FFA) project, she came up with a business plan for saving the farm that entailed making the switch to retail—selling milk directly to customers. If they did that, they could turn a profit and stay in business. But they’d need a few things: certification to sell, bottling equipment and a customer base.

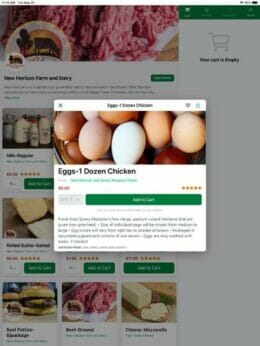

They started selling their other products, such as beef and eggs, directly to consumers on a platform called Market Wagon. Market Wagon is a food delivery service for farm products. The Bickels knew that if they established a presence on the platform with their other items, they’d have customers waiting when they were ready to sell milk.

Maggie’s plan ended up winning an award in a national FFA entrepreneurship competition. And her parents agreed that it wasn’t just a good student project—it could actually work.

And it did.

Farm to front door

Market Wagon functions as an online farmers market, allowing the Bickels to tap into a group of consumers who want to buy directly from producers. In 2020, the Bickels started selling milk under the label Happy Cows Creamery. They offered standard, fresh milk, but they eventually also added fun flavors such as orange creamsicle, chocolate and strawberry. They also use Market Wagon to sell products such as soft cheeses and rolled butter.

“We started delivering the milk through Market Wagon and we haven’t looked back since then,” says Bickel. She adds that the dairy exit strategy they had once been contemplating is not even on the table anymore.

Here’s how it works: Farmers update the site with what they have for sale that week—fresh produce, dairy, meat, prepackaged meals and more. Customers shop across categories and vendors. They submit orders by a pre-set deadline, and farmers take their items to the Market Wagon hub in their area.

“For a Tuesday delivery, about one in the morning on Monday, we receive what’s called a ‘pick list’ from Market Wagon,” says Bickel. “It’s basically a list that is broken down by customer and it is also broken down by product. So we have a whole day to assemble the orders.” She drives the order in, disperses the items amongst the individual customer tote bags, and then heads back home.

Gig drivers then deliver the items to their destination. This process happens weekly or biweekly.

Individual customer orders are assembled at local Market Wagon hubs. (Photography courtesy of Market Wagon)

Grocery delivery is nothing new, but many produce delivery systems rely on national supply chains. Some, such as Farmhouse Delivery, offer a similar farm-to-doorstep model rooted in Texas agriculture, but they also offer certain items from out of state. As opposed to a typical grocery delivery service like Instacart, Market Wagon aims to keep things as local as they would be at an in-person farmers market while using its online marketplace to aggregate at a scale that is difficult through traditional methods.

“You would have to go to a farmers market every night to reach the number of people that you do through Market Wagon,” says Bickel.

Customers buy directly from producers, just like in a physical farmers market. But there are differences, too: Farmers only bring what they’ve already sold to the hub, instead of having to guess what they’ll sell that day.

“There is a pipeline from local farms and makers to consumers, but it’s narrow and twisty,” says Dan Brunner, co-founder and chief executive officer of Market Wagon. “And we’re here to widen that pipe.”

Farmer to consumer

Brunner says a lot of consumers long to know where their food is coming from. And while farmers markets allow you to look your grower in the eye, Market Wagon tries to keep personal touches as part of its technology, by allowing for direct communication and emails between consumers and farmers.

“As an online marketplace, technically, we don’t need to replicate that—we can’t totally replicate that,” says Brunner. “But enabling consumers to ask those questions and get answers is a central thing that we felt like we just couldn’t live without.”

Screenshot of Market Wagon order screen. (Photography courtesy of Tom Hodson)

But, in practice, the online community does sometimes spill over into the real world. Bickel says they have a loyal customer base now and often have their Market Wagon regulars come visit the dairy, see the baby calves and pick up items at their farm stand.

“Now more than ever, it is so imperative for us to have a voice with the consumer,” she says. “So, we love to talk with our customers and answer questions.”

Market Wagon does not ship anything—everything is kept within a tight radius of where it’s grown or raised or made.

“It’s really a unique business model, because, instead of building a national distribution pattern for the same products, we are actively trying to have a different supply chain in every single place we’re operating,” says Brunner.

Tom Hodson is a loyal customer of New Horizon Farm and Dairy’s Happy Cows Creamery through Market Wagon. He orders weekly and favors their eggs and baked goods. Hodson, descended from farmers and an advocate of eating locally, likes that Market Wagon allows him to know exactly where his food comes from and how it was grown.

“What you see on the screen is exactly what ends up getting delivered in your order,” says Hodson.

In his retirement, Hodson has also begun driving for Market Wagon twice a week, and he says he hears that same sentiment echoed by many of the customers he meets. They like buying directly from local farmers.

Market Wagon tote bag with produce. (Photography courtesy of Market Wagon)

Pre-pandemic, Market Wagon existed in six markets in Indiana and Ohio. But the advent of COVID-19 highlighted the benefits of having groceries delivered to your door. Today, Market Wagon is in about 25 markets overall in the Midwest. Brunner foresees continual expansion into areas that could use a service like this—aimed at helping farmers thrive in their local markets.

This fortified resiliency is something that Bickel can attest to. Thanks to Maggie’s business plan and the resulting partnership with Market Wagon, her second-generation dairy farm appears to have a future as a third-generation dairy farm.

“We’re just trying to be as sustainable as possible with every resource that we have so that the farm is available for the next generation and the generation after that,” says Bickel.

The post The Farmers Market, Delivered appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Microbes, Mealworms and Seaweed Could Inform the Future of Cheese appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>It has to be flavorful. It should become gooey and stringy when melted. It needs to perfectly balance an acidic tomato sauce.

But does it have to be made from animal dairy?

The cheese innovators over at New Culture would say no. Their first product, a mozzarella cheese created with casein protein made through precision fermentation—that is to say, not from a cow—is launching in Nancy Silverton’s Pizzeria Mozza in Los Angeles in 2024. Silverton and Pizzeria Mozza have received numerous accolades over the years, including the 2014 James Beard Foundation Award for Outstanding Chef.

Precision fermentation is the process of engineering microbes to make something specific during fermentation. Inja Radman, co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer of New Culture, says its microbes are experts at making casein, a protein found in mammalian milk that’s full of nutrients for animal offspring. It also happens to be the protein that gives cheese, well, its cheesiness. The melt, chew, crumble and ooze of cheese are all thanks to casein.

“Everything we know and love about cheese really comes from casein,” says Radman. By making milk protein without milk, Radman and the others at New Culture are making “cow cheese without the cow.”

New Culture is part of a wave of scientists and innovators asking how the future of cheese will look. Some, like New Culture, aim to reduce or eliminate the dairy component altogether, while others seek to improve the dairy cheese process overall using unexpected allies.

Microbe-made casein protein. (Image courtesy of New Culture)

Sea cheese

One day, you might be able to buy cheese made with help from an unlikely source: seaweed.

A critical first step in making cheese is coagulating milk. In traditional cheese-making, this happens thanks to rennet, an enzyme derived from calf stomachs. But there’s not enough rennet to meet the global demand for cheese, so most cheeses in US commercial markets are made using alternatives. These alternatives have their own shortcomings, says Jian Zhao, associate professor in the School of Chemical Engineering at the University of New South Wales and one of the researchers looking for rennet alternatives. For example, the taste doesn’t quite hold up to traditional cheese.

“There is a continued need for the industry to explore new alternatives,” says Zhao.

In a recent research project, Zhao and his team turned to the ocean to look for an enzyme that could interact with milk similarly to rennet—coagulating it within an efficient timeline. They weren’t the first to consider the ocean as a potential provenance for this enzyme, but they took the research furthest, isolating a particular species of seaweed called Gracilaria edulis and actually using it to make cheese.

Gracilaria. (Photo: pokku/Shutterstock)

Of the seven seaweed species they tested, G. edulis was the only one to quickly coagulate cheese. The researchers used it to make two cheeses, an aged cheese similar to cheddar and a fresh one more like ricotta, and they were given to a taste-testing panel.

The cheddar was too bitter, says Zhao. But the ricotta? “The quality is quite good,” he says.

You won’t see seaweed ricotta in stores just yet. More research needs to be done to show that seaweed enzyme cheese can produce a product on par with other cheeses. Then, says Zhao, they’d need adventurous cheesemakers to start trying it out.

When it comes to making “sea cheese,” as Zhao calls it, it’s more than likely there are other enzymes in the ocean waiting to be identified.

“I’m pretty confident there are more species which will have the ability to coagulate milk,” says Zhao. “And they potentially can do a better job than Gracilaria.”

Hybrid cheeses split the difference

Clara Talens, senior researcher at AZTI, a Spanish research center that focuses in part on food innovation, sees a future for hybrid cheese.

Hybrid cheese—a milk-based cheese supplemented with plant-based ingredients—can help ease the transition toward more plant-based products, says Talens. The presence of milk makes the cheese’s taste and texture familiar to consumers, but the environmental impact is lower because it uses less dairy. Cheese has a hefty environmental footprint, due to the land use and greenhouse gas emissions associated with dairy farming.

“If we keep feeding our world with animal-derived proteins at the pace we are now, it’s not possible to feed us all,” says Talens. That doesn’t mean eating animal protein is inherently bad, she says, just that the rate is unsustainable.

Added proteins can come from sources such as insects or pulses such as chickpeas. In a recent study, Talens and her team used insect flour made of mealworm larvae and flour made of faba beans (also sometimes called fava or broad beans). These ingredients were chosen because they are high in protein but are not as resource-intensive to cultivate.

“It’s a matter of the resources needed to produce a kilogram of protein,” says Talens.

Faba beans. (Photography by @boulham/Shutterstock.)

Talens analyzed different ratios of milk protein to faba bean protein to insect protein. The researchers looked to both dairy cheese and plant-based cheese as reference points, analyzing the resulting mixtures for their nutritional value, taste and texture.

The researchers found that the texture of the faba bean was good, especially when combined with the milk protein. The insect protein did not contribute well to structure, but it gave the cheese an umami-like taste similar to certain aged cheeses.

Another group of researchers from Denmark also looked at the potential for incorporating plant proteins to make hybrid cheeses, and concluded that this area shows great potential—once cheeses are developed that offer satisfactory taste and texture. And in the US in 2021, cheese company The Laughing Cow tried out the concept by releasing hybrid spreadable cheeses that included lentils, red beans and chickpeas.

Still, says Talens, instead of striving to create direct imitations of traditional cheese, maybe another mindset shift is in order.

“We should open our minds and accept all the flavors and other tastes that are produced by using other raw materials,” says Talens. “But still, that’s the most difficult part. With the hybrids, maybe we are a bit closer to acceptance.”

Cheese for everyone

Once the microbes at New Culture make casein, it’s combined with plant-based fats and other ingredients and made into cheese using a similar process to standard cheesemaking, thanks to the fact that the microbially made casein performs the same as casein from cow milk.

“It’s identical to casein we would get from milk,” says Radman. There just wasn’t an animal involved.

New Culture mozzarella. (Image courtesy of New Culture)

Radman says there was a reason they chose to make mozzarella as their first product. Pizza is everywhere in the US, and pizza is made with mozzarella. New Culture doesn’t just want to market to vegans.

“This is a cheese for everyone,” says Radman.

And since it’s a pizza cheese, she adds that it’s something that people can share without anyone in a group compromising on values or taste. “That means this is a cheese that brings people together.”

The post Microbes, Mealworms and Seaweed Could Inform the Future of Cheese appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post ‘An Insane Amount of Water’: What Climate Change Means For California’s Biggest Dairy District appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>But the epic flooding this past March was simply unprecedented, says the owner of Lerda-Goni Farms. After a winter of record snow in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, a sudden warm spell melted the lower reaches, unleashing nearly 40,000 acre-feet of water—a volume equal to more than a tenth of Las Vegas’ annual supply—in 48 hours. The torrent overwhelmed dams, swelled rivers and crumbled levees, inundating entire farming communities, including Lerda-Goni and a dozen other ranches, and reawakening a long-dormant lake lying beneath the vast agricultural region.

With floodwater breaching six-foot high banks, “I don’t know what we could have done to prevent it,” says Goni. “It was just an insane amount of water in such a short amount of time.” Months later, he’s still shell-shocked from having to relocate his herd of 2,400 cows in the middle of the night—a Herculean effort pulled off by his team of 11 long-time employees, neighbors and countless volunteers, some who hailed from as far away as Nevada.

The reemergent Tulare Lake is not expected to drain for up to two years. (Photo courtesy of Lerda-Goni Farms)

All told, one official estimate pegs the dairy industry’s losses at $10 billion. While the lake has drained down to about 168 square miles, a chilly spring also kept the high-elevation snowpack at a slow melt, helping to avert an even greater calamity in the low-slung basin. Yet, as whole farming communities dig themselves out of the muddy ruins, the growing uncertainty of climate change is darkening a cloud over the future of the region’s largest industry—one valued at nearly $2 billion annually.

Following multiple years of drought, the diluvian whiplash is just the latest in a mounting list of burdens facing the basin’s largest industry, which pumps out 54 percent of California’s milk supply. As environmental adversity—along with the strain of rising costs and regulations—tightens the squeeze, many smaller, family-owned ranches have been caving to consolidation pressure. And that’s tipping the landscape in favor of mega-dairies—the large-scale operations that critics point to as disproportionate contributors of human-induced climate change.

At this point, “our farm is pretty self-sufficient,” says Goni, as he rushed to plant summer feed corn on his barely dry fields. His 580-acre farm grows enough forage to supply the herd, so “I’m good with where I’m at,” he adds. Still, the trend of getting big or getting out is all too real, adds the farmer, who’s seen plenty of small dairies pushed out in his lifetime. “But I’ll leave that [decision] for my nephews, for the next generation.”

![]()

Located in the southern reaches of the San Joaquin Valley, about 200 miles north of Los Angeles, Tulare Lake was once the largest body of freshwater west of the Mississippi River. Fed by four rivers flowing from the Sierra Nevadas, the shallow inland sea covered 1,000 square miles—more than four times the surface area of Lake Tahoe. Vast tule marshes surrounded its banks, creating a rich ecosystem teeming with fish and birds that, in turn, supported the Tachi Yokut and other Native American communities.

As westward expansion swept across the region in the late 1800s, settlers began draining the 40-foot deep lake for farmland. Within decades, a network of dams, levees and canals had dried up the basin, transforming the fertile crater into an agricultural hub. Today, the four counties sitting in the lake bed account for more than $25 billion in food and crop production, with Tulare County ranking number one in the nation for milk and oranges. Neighboring Fresno and Kern Counties top the list for almonds, while Kings County rules the state in cotton production.

But thirsty crops and cattle have taken their toll: Amid California’s cycles of drought, excessive groundwater pumping has left Central Valley basins the most overdrafted in the state. Although California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) aims to recharge them by regulating draws, the dried-up lake bed has long been collapsing under the massive weight of industrialized agriculture—to the tune of a couple of inches per month.

As climate change fuels more extreme swings in weather patterns, subsidence further compounds the region’s issues, says John Abatzoglou, professor of climatology at University of California, Merced, with arid years advancing the sink and wet ones expanding flood risk.

The tanking basin is also wreaking havoc on the region’s extensive canal system and levees. Corcoran, a community of 22,000 in Kings County with a sizable population of agricultural laborers and a large state prison, is scrambling to raise its 14-mile-long embankment, which has already collapsed by several feet since getting a $10-million boost just five years ago. As future deluges become more severe, maintaining, repairing and upgrading valley infrastructure will require greater investment, says Abatzoglou.

Dairy farmer Joseph Goni’s grandfather witnessed the 1955 deluge that flooded their farm. (Photo courtesy of Lerda-Goni Farms)

Since the 1983 flood, changes in farming patterns have also raised the basin’s economic risk, he notes. Orchards, vines and other perennials cultivated as long-term investments have steadily replaced ephemeral crops such as tomatoes and cotton, which are far less costly to sacrifice or replace. Meanwhile, the consolidation of dairies has led to a sharp increase in herd size despite a plummeting number of farms, reflecting a national trend.

“It’s a different playing field,” says Abatzoglou. Ultimately, the altered landscape means that climate-related disasters including floods, wildfires and drought will all take a deeper toll on agriculture—fruit and nut farmers having to abandon decade-old trees, for instance, or cattle ranchers needing to relocate hundreds of thousands of cows at a moment’s notice. And that’s on top of less snowpack and quicker melts thanks to a warming climate, as well as shrinking milk production from heat-stressed herds.

![]()

As individual farmers reel from the most recent disaster, many are up against the consequences of a new normal, says Anja Raudabaugh, chief executive officer of Western United Dairies, a Fresno-based industry trade organization. “Insurance carriers are not going to tolerate this again,” she adds, so farmers in floodplains are bracing themselves for a range of costly upgrades, including raising the elevation of entire feed lots and barns.

In an industry known for razor-thin margins and a grueling, 365-days-a-year schedule, Raudabaugh sees consolidation accelerating. Although herds of 1,200 used to be the norm not too long ago, small family dairies are increasingly merging into 4,000- to 6,000-head operations. Larger players have more buying power and efficiency to manage rising operational costs, she says, so “becoming bigger is like a risk buffer.”

And in recent years, the soaring cost of feed and water scarcity—both compounded by drought and SGMA regulations—have made consolidation pressure all the more acute in California. “Despite the resilience of family [farms], the mega-trend is undeniable,” says Raudabaugh.

With the growing scale comes a ballooning environmental footprint: More inputs of feed and water increase output, which includes greater methane emissions. Dairy and livestock account for more than half of California’s production of the powerful greenhouse gas (GHG), one that traps 84 times more heat than carbon dioxide.

In Tulare County, where nearly half a million milk cows live on 222 dairies, the sheer density of large operations also magnifies other impacts, says Andrew deCoriolis, executive director of Farm Forward, a Portland-based humane farming advocacy organization. Concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) have been linked to numerous environmental issues such as nitrate contamination of groundwater and bacterial runoff, as well as dust storms and poor air quality (the county ranks among the worst in the nation).

“On a local and regional [level], it would be hard to point to another industry—except maybe oil and gas refining—with as much emissions and pollution,” he adds.

For their part, dairy farmers are duly engaged in sustainability efforts, says Raudabaugh. She points to wide-scale implementation of anaerobic digesters, which capture methane from sealed manure lagoons to create biogas. “They’re currently the only technology in the entire state that reduces methane,” she adds. Under a California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) program aimed at slashing the state’s GHG emissions by 40 percent, she estimates that dairy farms have installed more than 200 projects, with an additional 25 currently in development.

Bio-digesters can help dairies cut emissions, but they’re costly. Critics say they create the wrong incentives. (Photo: Shutterstock)

A recent County report shows that, in the last decade, bio-digesters helped Tulare’s dairies and feedlots reduce their emissions by nearly 20 percent. And because the entire system is sealed, dairy digesters went unscathed during the spring floods, Raudabaugh notes, preventing vast acres of effluent from escaping.

Harnessing methane also helps farmers build economic resilience. At the federal level, participants can earn clean fuel credits through the Renewable Fuel Standard program, while in California, biogas producers can also sell their carbon credits to oil and gas companies. All told, the added revenue could boost a dairy’s earnings by as much as 50 percent.

Critics, however, remain skeptical. With one digester costing anywhere from $400,000 to $5 million to install and operate, smaller operations often find them cost prohibitive. Yet for those that can afford them, it’s an enticing cash cow, says DeCoriolis, with a return on investment that scales up with increased methane production. “The value of the energy is great enough that it’s creating these perverse incentives to grow CAFOs.”

And it’s not just the manure, he adds—cows also burp 220 pounds of methane annually. “We’re subsidizing [the expansion of] these megadairy operations, all [in the name of] renewable energy,” says DeCoriolis. “And it isn’t going to do anything to reduce the other negative impacts.”

![]()

Size is relative, says Daniel Sumner, professor of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California, Davis. With the country’s average herd ranging around 300 heads, “just about all dairies in California are considered large by U.S. standards,” he writes in an email. But, he adds, the scale helps keep the Golden State’s dairy prices in check.

California’s small, pasture-based, organic dairies—many of which are clustered on the state’s North Coast—have a lighter environmental footprint, and they contribute just a sliver of the industry’s overall methane emissions. Yet that comes with high production costs that run 50 percent greater than Tulare County operations, says Sumner.

Although the premium operations fill a niche market, large-scale ones keep dairy accessible to Californians far beyond the grocery aisle, says Western United’s Raudabaugh. Consumer groups include food assistance services, including school nutrition and the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) programs, as well as food banks, prisons and other public institutions. “There’s more cheese, yogurt and milk being consumed in these [services] than ever before,” she adds.

Dairy is also tightly woven into the fabric of California agriculture. Despite competing for land and water, the region’s orchards and milk farms have developed an unlikely partnership, says Sumner. Cows consume vast amounts of agricultural by-products, including almond hulls, citrus peel and other food-processing leftovers; the supplemental feed keeps crop waste out of landfill and “the dairy business afloat in the Valley,” he adds.

The field is further ingrained in the local and state economy. California produces nearly 42 billion pounds of milk annually, which, together with dairy products, total nearly 15 percent of California’s $51-billion annual agricultural production. And because the fresh fluid is costly to transport, dairy processing is highly regional, says Sumner. Statewide, the industry is responsible for almost 180,000 jobs, he notes, and supports another 132,000 indirect ones through trucking and hauling, veterinary services and other ancillary sectors.

Nearly half a million milk cows live on 222 dairies in Tulare County. (Photo: Shutterstock)

But a resilient industry needs a strong foundation to keep it from getting too top-heavy. And that means fostering a diverse range in the scale of farms, says Jeanne Merrill, the former policy director for the California Climate and Agriculture Network. “Agriculture [prospers] when small and mid-scale family operations can not just survive but thrive economically.” In other words, policy measures aimed at sustainability need to also support economic viability.

Merrill points to CDFA’s suite of climate smart solutions that promote agronomic benefits through financial incentives. The multi-pronged approach fosters conservation management practices that improve soil health and sequester carbon, as well as irrigation measures that reduce on-farm water and energy use. The Alternative Manure Management Program also offers a more cost-effective and greener alternative to bio-digesters, minimizing methane at the source by up to 90 percent and simultaneously generating compost.

And dairy farmers are increasingly engaging in recharging over-pumped basins. The California Department of Water Resources LandFlex program incentivizes growers to fallow fields during drought or, as the case may be this year, flooding them in years with heavy rain to replenish regional aquifers.

These state incentive programs all help to keep family farms in business while advancing innovations. “It keeps the land [active] and on [a farmer’s] asset sheet,” says Raudabaugh, “so he can still pay his employees, bank notes and property taxes—all of which keep the local community going.”

The programs also help mitigate some of the risks of implementing innovation, adds Merrill. California farmers are a highly motivated group, she says. With program demand far exceeding available funding, “we’re seeing that they really want to engage in practices that’ll make a difference on their operations.”

Still, the looming challenges of climate change are daunting, Merrill concedes, and require much more ambitious action. “We have to bend that emissions curve in order to avoid some of the worst impacts, and in agriculture… these changes take time,” she says. “So, we have to invest now in order to reap the rewards later.”

ThThis story is part of State of Abundance, a five-part series about California agriculture and climate change. See the full series here.

The post ‘An Insane Amount of Water’: What Climate Change Means For California’s Biggest Dairy District appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Is Whole Milk Headed Back to School? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>For the children in Greenville Central School District in upstate New York, the question is a no-brainer. Hands shoot up, and a chorus of eager voices cries: “Me!” “Me!”

Duane Spaulding reaches into a cooler on the back of his maroon pickup truck, grabs a handful of whole chocolate milks and hands them out to the gaggle of preschoolers. “It should taste like a melted milkshake,” he tells them with a smile.

It’s a rare treat for these youths.

America’s public schools last served whole milk in 2012, two years after Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The law strengthened nutrition standards for meals provided through the National School Lunch and Breakfast programs, with the goal of increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and reducing childhood obesity and diabetes. Whole milk and 2 percent, with their higher fat contents, were casualties of the stricter guidelines.

But on this balmy day in late May, Spaulding, a former dairy farmer, and Ann Diefendorf, a sixth-generation dairy farmer from Seward, N.Y., are giving out whole milk on school grounds.

The two are distributing fliers touting whole milk’s nutritional properties at Ag Day, an annual event sponsored by the district’s Future Farmers of America chapter.

“We’d just like to get whole milk back in school as a choice,” Spaulding explains to the adults escorting children through Ag Day attractions. “So, if anyone can help, it’s a grassroots movement.”

One woman nods, scanning the fliers. “I completely agree with that,” she says.

This is the reaction Spaulding and Diefendorf want. The ban on whole milk in public schools is an ongoing source of discontent for dairy farmers and their allies in agriculture. They say whole milk is good for kids and that children will reject milk altogether and miss out on essential nutrients, such as calcium, potassium and vitamin D, if the only options are skim and low fat, which aren’t as tasty.

“I don’t want these kids in school thinking that’s the milk we produce,” says Diefendorf, who owns 45 dairy cows. “We produce whole milk. That’s what goes out in the milk truck every other day. And for those who are so far removed from the farm community, they don’t know.”

Spaulding, 64, and Diefendorf, 60, are involved with 97Milk, an all-volunteer organization seeking to reverse the ban on whole milk in public schools. Outreach and education are a core part of 97Milk’s mission, and the group’s name addresses one common misconception: the mistaken belief that whole milk is all or mostly fat. In reality, it’s only about 3.25 percent fat—“virtually 97 percent fat-free,” as the organization’s materials put it.

Duane Spaulding distributes chocolate milk to students from Greenville Central School District in upstate New York. (Photo: Sara Foss)

The intensifying activism around milk comes at a time of angst and anxiety for dairy farmers, who have struggled to break even for years as costs have risen and prices have slumped. Adding to the stress is that Americans are drinking a lot less milk.

While not a new trend—consumption has been dropping since the mid-1940s—the decline accelerated faster during the 2010s than in each of the previous six decades. Between 2003-2004 and 2017-2018, children’s consumption of milk and milk drinks fell 26 percent, from 1.07 cup-equivalents per person per day to 0.79, according to a 2021 USDA research report.

Data like this fuels concern that the dairy industry is losing ground with the youngest generation, the people who will become the customers of tomorrow. Also worrisome for farmers: The USDA is considering eliminating flavored milk in elementary and middle schools when it adopts new school nutrition guidelines for the 2024-2025 school year.

97Milk got its start in late 2018 when Nelson Troutman, a retired dairy farmer from Richland, Pa., placed a wrapped hay bale with a message urging people to drink local whole milk at an intersection near his farm.

Frustrated by a listening session with the Pennsylvania Milk Marketing Board—“they wine and dine the farmers, and then they go home and nothing happens”—Troutman decided to take matters into his own hands. “I said, ‘I’m going to start advertising that milk is 97 percent fat-free,’” he recalls. “I can paint that on a hay bale. It will look neat.’”

The bale did look neat. It went viral online and spurred media coverage. From there, organizing began, and hay bales began to proliferate. There are no formal records of how many bales have been painted or where they are, but Diefendorf estimates she has painted at least 50 in upstate New York. A 2022 article in Lancaster Farming reported that pro-whole signage had been spotted in at least seven other states, including Kansas and Ohio.

“The kids in school get skim, and they hate it, and they throw it away,” says Troutman said. “Our big thing is: Where is the nutrition? It’s in the garbage can.”

The resistance to reintroducing whole milk and 2 percent to public schools comes from health organizations that say skim and low-fat milk have the benefits of whole milk without the empty calories of the creamier beverage’s saturated fat.

Samuel Hahn, a policy co-ordinator on the school foods team at the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington, D.C., says school meals have become much healthier under the nutrition standards enacted in 2010. He says there’s little evidence that kids prefer whole milk to skim and low and that the research suggests what children really want is chocolate milk.

“What matters a lot more [to kids] is whether the milk is flavored as opposed to its fat content,” says Hahn. “As an organization, we’re not opposed to having flavored milk in school meals. We’re not opposed to milk at all. We just want to make sure it’s fat free or low fat, and if it is flavored, that it’s low in added sugars.”

“What matters a lot more [to kids] is whether the milk is flavored as opposed to its fat content,” says Samuel Hahn, a policy co-ordinator at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. (Photo: Shutterstock)

While leading health organizations, such as CSPI and the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommend children switch to low-fat and skim milk at the age of two, there’s disagreement within the broader health community on the merits of that advice.

“From a nutrition standpoint, whole milk is a great source of nutrients and really isn’t the problem with childhood obesity,” says Beth Chiodo, a registered dietitian who serves as public relations chair for the Pennsylvania Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Some studies “have shown that kids who drank whole milk were at a reduced risk of being overweight and less likely to be obese,” Chiodo continues. “A bigger driver of childhood obesity is high-fructose corn syrup, snack foods, processed food and fast food. These foods are calorie dense and aren’t providing any of the necessary nutrients kids need.”

In its brief existence, 97Milk has gained some powerful political backers.

Earlier this year, U.S Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson, a Republican from Pennsylvania, and Rep. Kim Schrier, a Democrat from Washington, introduced the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act, which would allow unflavored and flavored whole milk to be offered in school cafeterias. This is the third time Thompson has introduced the bill, which has 100 co-sponsors from 37 states. In June, the House Education and Workforce Committee approved the bill in a 26-13 vote. The next step is to schedule a vote by the full House of Representatives.

Similar bills have also been introduced in New York and Pennsylvania, where 97Milk is most active.

“Banning whole and 2 percent milk was an ill-advised policy change,” says Rep. Chris Tague, a New York state assemblyman whose district includes Schoharie County, where Spaulding and Diefendorf live. “It has not served our young folks well, and it’s also hurt our dairy farms.”

Tague, a former dairy farmer, is a co-sponsor of a bill that would put whole milk and 2 percent back in New York schools by allowing districts to serve milk produced by New York farms. Supporters contend that such milk has not entered interstate commerce and is outside federal jurisdiction. It’s unclear whether the bill, if passed, would survive a legal challenge.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, published every five years by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, recommends that those two years and older limit their intake of saturated fat to less than 10 percent of calories per day. If schools were permitted to serve whole or 2 percent milk, it would be difficult for them to menu these items regularly and still meet strict federal limits on calories and saturated fats. Thompson’s bill would increase the amount of saturated fat allowed in meals to account for the milk fat in whole milk.

During Diefendorf’s visit to Greenville, she painted an 800-pound bale to donate to the district during breaks from greeting children and handing out milk. The slogan: “Look Up 97Milk.com. Support Dairy Farmers.”

For Deifendorf and Spaulding, it will be a busy summer attending community events, fairs and other outdoor gatherings to share their message. The reception is overwhelmingly positive at Greenville Central School District, where many children come from farming families.

“That is really good!” one boy yells after sampling the chocolate milk.

“Of course,” says Spaulding. “We brought nothing but the best.”

The post Is Whole Milk Headed Back to School? appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post For Years, Farmers Milked Cows by Hand. Now Robots and Technology Do the Work appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The milkers are squat, patient, persistent workers. They hum around the mooing cows. They are robots.

In an increasingly automated world, the dairy industry is keeping up. According to Michigan State University, robotic milkers were first introduced in the United States in 2000. Now, according to Hoard’s Dairyman magazine, over 35,000 robotic milking units can be found around the world, with thousands in the US.

“It’s always changing. It’s like your iPhone getting changed every six months. There’s lots of technology that’s getting researched every day,” said Dana Allen, a fourth-generation dairy farmer from Eyota, Minnesota.

Dairy technology has transformed the industry.

Decades ago, dairy producers milked by hand. Then came buckets, pipelines, parlors, and then parlors with automatic unit removal, rotary parlors, and robots, according to Douglas Reinemann, Ph.D., a researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Automation started in Europe. Company DeLaval started using an automated robot system at a farm in Sweden in 1997. Another maker is Lely, based in the Netherlands.

By 2000, automation came to the US. The results are significant, farmers and researchers say. Cows feel less stress, farmers are able to be more efficient and they gain time. They also save money on labor.

Now there are 500 to 1,000 U.S. operations using the milking robots, said Reinemann.

The automation is not perfect. Startup costs challenge smaller producers. As with most machinery, there also is the need for maintenance.

The robot automatically sucks the teats of the cow. (Photo by Ethan Humble, for Investigate Midwest)

Farmers gain time to work

Automated milking systems (AMS) give farmers time to focus on other work, and typically more time on skilled duties. This saves labor, Reinemann said. He also noted that AMS helps farmers ergonomically as they avoid repetitive physical tasks.

Farmers who use AMS appreciate the labor savings.

“The farmers have more time to clean up the farm, work on the crops, and other chores. It may even allow a farmer to attend their kid’s sporting events and in turn, improve their mental health,” said Mariah Busta, executive director of the Iowa State Dairy Association.

But the rate of change is up to the farmer.

“The degree to which a farmer adapts to technology and the speed at which they do it is open for their comfort level,” Allen said. “There is a tremendous amount of technology in agriculture, and I think that’s something the general public doesn’t understand.”

Robots leave cows calmer

Robots, like Kieffer’s, milk cows without the physical presence of a human being, using a robotic arm with the aid of either 3D cameras or laser beams to locate a cow’s teats.

According to the Animal Agriculture Alliance, a nonprofit focused on sustainable ag, the total time needed to milk one cow takes an average of seven minutes with a robot.

Since installing robots, Kieffer has reduced his number of full-time dairy employees from six to three.

“The robot is doing the milking for you, so the cost of the robots has to be offset by labor savings,” he said. The robots can cost more than $200,000 each.

The farmers also said the cows’ comfort is a critical benefit. Reinemann said cows can associate humans with negative interactions, such as a veterinarian checkup or being moved to and from different buildings.

“You’re allowing a cow to do what she wants when she wants. You’re not forcing her somewhere, and she can go get milked,” Kieffer said.

Cows voluntarily can go to the area indoors to be milked, farmers said. The robot system sorts cows that need to be milked based on how much time has elapsed in between milkings. Ear tags assist with sorting.

In Deer Park, Wisconsin, Kristin Quist of Minglewood Dairy keeps about 500 of her herd of 1,200 cows in a robot milking facility. She uses a system that guides the animals through the barn.

“The cow walks through a gate determining if it’s time for them to be milked after reading a tag in her ear,” she said. “If it’s time to be milked, she goes into the robot. If it isn’t, she’s sent to be fed in a different direction.”

Quist compares her newer robot facility to her milking parlor.

“The cows in the robot facility are a lot more laid back,” she said. “In the parlor facility, they are more likely to get up expecting to get milked.”

Regardless of the production method, farmers are producing more milk, primarily because of improved genetics and improved nutrition, researchers said.

Reinemann said research has shown using robots allows cows to remain in the herd longer, which can mean they produce milk longer.

“We won’t be getting any additional land or resources in the coming future, so we need to be efficient with what we have,” Busta said. “Technology is absolutely crucial in helping us continue to be efficient about producing milk in a sustainable way.”

A view of the inner structure of the rotary shows how it supports 50 cows at Gar-Lin Dairy in Eyota, Minnesota. (Photo by Ethan Humble/for Investigate Midwest)

Other farmers opt for rotating platform systems

Farmers seeking an upgrade have other options beyond milking robots.

Rotary milking parlors allow cows to step onto a circulating platform before farmers attach milking units. The system constantly moves cows on and off the platform.

Allen milks her herd of about 1,750 cows on her farm, Gar-Lin Dairy, using a platform. Gar-Lin’s rotary allows 50 cows to step onto the platform at a time.

“Before, we were milking 750 to 800 cows in about seven hours. Now we can milk 1,750 in the same amount of time,” she said.

Allen said that she initially feared the cows would be difficult to get onto the carousel-like platform, but she quickly learned the greater issue would be getting them off.

“There’s not a lot of commotion,” she said. “They actually like riding around on the rotary.”

In deciding what type of system a farmer should pursue, a farm of 1,500 to 3,000 cows likely warrants a rotary system, while a herd of 200-300 cows may be better suited for robots, said Marcia Endres, Ph.D., a professor of animal science at the University of Minnesota. With larger herds, a rotary system is more efficient because up to 50 cows can be loaded at once, though it does still require human intervention to get the cows on the platform.

One benefit of technology is more milk. In 1925, the average Iowa cow was giving 4,000 pounds of milk each year, while today’s cow gives 28,000 pounds annually, according to the state dairy association.

Some farmers are weighing the pros and cons of the technology.

Among them is Nick Seitzer, a recent University of Minnesota grad and dairy farmer from St. Peter, Minnesota. He’s thinking about adding a robot to milk his 65 cows. He forecasts about a 10% increase in production if he installs a robot in a free-stall barn.

“The robot would be huge,” Seitzer said. “Fewer people want to do what we’re doing, so it would be nice to have robots that are always there doing the job.”

But the initial cost is high. Seitzer estimates one robot would cost about $250,000, not including the physical infrastructure (such as a potential barn expansion, milk house or other needs) to use it.

A heads-up display monitors the milking progress of the cow compared to its expected yield. (Photo by Ethan Humble, for Investigate Midwest)

On his Utica, Minnesota, farm, Kieffer saw robots as a smart investment. Kieffer typically spends one hour a day doing maintenance, he said.

“Your debt per cow or debt per stall becomes rather large up front, but what I tell people is you’re basically prepaying your labor for seven or eight years,” he said. “It ends up being less than a traditional herd of cows being milked in a parlor.”

With dairy technology rapidly changing, Seitzer has been feeling pressure for his operation to adapt.

“If we don’t, we may not be doing it much longer,” he said.

Dr. Lindsey Borst, a veterinarian who milks 230 cows alongside her family in Rochester, Minnesota, feels differently. Borst has been looking at robots for five to six years.

“I wouldn’t say we’re falling behind. Robots are still fairly new, and they’re not super common yet,” she said. “Sometimes it’s also good to wait because technology is changing so quickly, too.”

Robots are not the right choice for all farmers, Kieffer, the farmer, and Endres, the University of Minnesota professor, said.

“Don’t put robots in because you don’t like cows. You also have to be mechanically inclined to do preventative maintenance on the robots,” Kieffer said.

Reinemann, the UW professor since 1990 and director of the UW Milking Research and Instruction lab, grew up in the dairyland of Wisconsin.

“For me as a young person, milking cows was so ordinary; there was absolutely nothing interesting about it,” he said. “I started my career in milking technology, and it’s been amazing. The shifts in the technology and how dairy farms are managed, it’s been a lot of change.”

Investigate Midwest is an independent, nonprofit newsroom. Our mission is to serve the public interest by exposing dangerous and costly practices of influential agricultural corporations and institutions through in-depth and data-driven investigative journalism. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org

The post For Years, Farmers Milked Cows by Hand. Now Robots and Technology Do the Work appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Sustainable Farmers See Promise in New Financing Options appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Like many small family farms, Dharma Lea has faced relentless pressure to expand, whether it wanted to or not. The farm needs loans, but traditional funders typically build growth into their financing terms. Hitting a wall with conventional funders, the Van Amburghs recently found a loan from a new type of lender.

Pressure to expand

“Farm Credit tells people, ‘Look, we’ll [lend] you more money, but you’ve got to grow, you’ve got to milk more cows’—that’s implicit in their loan agreements,” says Paul. “‘We will finance your next million, but you’re gonna have to put on another 500 cows.’ And now you’ve got farms that are too big to fail. And is that really where we want to go?”

“Every farm started out as a small farm,” says Phyllis. She and Paul tell the story of a farmer, barely making ends meet, who hoped to hit an economy of scale by adding a thousand cows. The way the Van Amburghs see it, the economy of scale is a false hope. If you’re just breaking even with a thousand cows, the situation won’t change with two thousand cows. Phyllis describes the demand to grow as a runaway train of debt.

“We have this old friend who has always milked 20 cows,” says Paul. “He said, ‘I’m losing five dollars a head, milking cows; why would I want to milk more?’ And it was just brilliant. Actually, he understands fixed and variable costs perfectly.”

Cows grazing a field at Dharma Lea Farm.

Depth, not breadth

The Van Amburghs are adamant that the only way off that debt train is long-term investment in quality. When the land and livestock are healthier, a farm needs fewer external inputs, such as fertilizers, feed or antibiotics. And that means fewer variable costs, smoothing the farm’s financial peaks and valleys.

When the Van Amburghs think of debt, they don’t just think of dollars. They think of ecological debt. “When you drive along the road and look at farms, of course, they’re beautiful. But people have no idea how degraded the resource base is. Yes, we purchased land, but we purchased an ecological debt with it. And paying that debt is the difference between surviving and not surviving in agriculture today,” says Paul.

Phyllis says their mentors encouraged them to “look at something bigger than our day-to-day cash flow. And beyond measuring the pounds in the tank—which, I gotta tell you, is a really hard habit to break when that’s what makes the whole thing turn.”

For example, the Van Amburghs learned to raise calves with their mothers. That is considered “blasphemy in the dairy industry,” says Phyllis, because calves drink milk the farm could sell. The practice harms short-term cash flow, but, in the long term, it yields “a cow that will be healthy and strong and live a long time problem-free,” she adds. “You need to invest in yourself first.”

Yet financing is challenging for those seeking organic certification or converting to regenerative agriculture. These approaches require long-term investment in the health of the land that can take years to build, but cash flow on a farm is notoriously short-term.

A calf nurses from its mother at Dharma Lea.

Pro-environment lending

Lenders investing in ecological health and tailoring loans to farms are crucial and scarce, but their numbers are growing. Programs such as the USDA’s Climate-Smart funding embrace farming practices that preserve the health of farmland and the environment. In contrast, traditional lenders favor large-scale monoculture farms, which Paul describes as “the ultimate oversimplification of a biodiverse environment.”

When a lender’s definition of “return on investment” includes environmental impact, it’s more likely that small farms can thrive without getting on the expansion train.

For example, when Walden Mutual Bank evaluates a farm for a loan, the bank looks for a solid return on investment. But it’s not the return you might expect. Walden seeks borrowers making a positive social and environmental impact. Walden, which received FDIC approval in 2022, is the first new mutual bank launched in the Northeast in several generations. It was founded specifically to support sustainable food systems in the region.

Walden was designed for the long run, says its CEO, Charley Cummings. One reason Walden’s founders chose the mutual bank structure was “because it is semi-permanent. Our objective was never to be sold to a global megabank,” says Cummings.

Mutual banks “make a lot of sense,” says Paul, because they have the discretion to be reasonable on rates and flexible terms. This discretion is possible because “nobody’s looking for returns that compete with the stock market.”

Walden lends to farms, like Dharma Lea, that have already embraced sustainable practices. It also seeks farms at the beginning of that journey and tracks their impact over time. Through its annual assessments, Walden collects best practices and shares them with all its agricultural customers. Walden’s borrower assessment uses criteria similar to B Corp certification, focusing on five areas: governance, community, workers, environment and customers.

Dharma Lea is one of Walden’s loan customers. “It’s kind of philosophical how they evaluate. And we need people to acknowledge that our answer to agriculture is real,” says Paul.

Before the advent of Walden and lenders like it, small farms had few loan options to support their sustainable practices. The federal Farm Service Agency (FSA) is considered a lender of last resort, as farms must be declined by three banks before they can apply to the FSA. And Farm Credit, a commercial lending co-operative, is geared toward larger farms.

Investing in the future

Organic certification, like regenerative agriculture, requires short-term financial support to yield a long-term payoff. “Certification requires you to use organic methods for three years. Before you receive organic certification, you incur all the costs of farming organically, but you don’t have any of the benefits in the marketplace. Because you can’t get a premium without that stamp,” Cummings explains.

In addition to newcomer Walden, Rabo AgriFinance in St. Louis offers organic transition loans. And Compeer Financial, a Farm Credit cooperative in the Upper Midwest, makes organic bridge loans. Compeer’s loan offers interest-only payments during the transition period and converts to a standard term loan once the farm is certified. The USDA’s Transitional and Organic Grower Assistance Program provides a $5 per acre subsidy during the transition, but it requires participants to purchase additional insurance.

Walden sees the Northeast as a perfect fit for this new type of financing. “In the last five to ten years, there has been this amazing renaissance of small-scale agriculture here. This is quickly becoming the center of the local food movement,” says Cummings.

Farming for impact

The Van Amburghs have five children, and they want to pass down not only the resource base of the farm but a healthier environment and climate. They see appropriate financing as a crucial part of the picture. “Farmers need help. If we gave people a bridge to transition, and we properly incentivized, a lot of very conventionally minded, linear-thinking farmers would become amazingly regenerative,” says Paul.

The post Sustainable Farmers See Promise in New Financing Options appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Opinion: Feeding Insects to Cows Could Make Meat and Dairy More Sustainable appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The world’s population is growing, and so is the challenge of feeding everyone. Current projections indicate that by 2050, global food demand could increase by 59 to 98 percent above current levels. In particular, there will be increased demand for high-quality protein foods, such as meat and dairy products.

Livestock producers in the US and other exporting countries are looking for ways to increase their output while also being sensitive to the environmental impacts of agricultural production. One important leverage point is finding ingredients for animal feed that can substitute for grains, freeing more farmland to grow crops for human consumption.

Cattle are natural upcyclers: Their specialized digestive systems allow them to convert low-quality sources of nutrients that humans cannot digest, such as grass and hay, into high-quality protein foods like meat and milk that meet human nutritional requirements. But when the protein content of grass and hay becomes too low, typically in winter, producers feed their animals an additional protein source—often soybean meal. This strategy helps cattle grow, but it also drives up the cost of meat and leaves less farmland to grow crops for human consumption.

Growing grains also has environmental impacts: For example, large-scale soybean production is a driver of deforestation in the Amazon. For all of these reasons, our laboratory is working to identify alternative, novel protein sources for cattle.

Black soldier fly larvae

An insect farming industry is emerging rapidly across the globe. Producers are growing insects for animal feed because of their nutritional profile and ability to grow quickly. Data also suggests that feeding insects to livestock has a smaller environmental footprint than conventional feed crops such as soybean meal.

Among thousands of edible insect species, one that’s attracting attention is the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). In their larval form, black soldier flies are 45 percent protein and 35 percent fat. They can be fed efficiently on wastes from many industries, such as pre-consumer food waste. The larvae can be raised on a large scale in factory-sized facilities and are shelf-stable after they are dried.

RELATED: Is It Ethical to Farm Insects for Food?

Most adults in the US aren’t ready to put black soldier fly larvae on their plates but are much more willing to consume meat from livestock that are fed black soldier fly larvae. This has sparked research into using black soldier fly larvae as livestock feed.

Black soldier fly larvae. Photo by Hanan Azhar, Shutterstock.

Already approved for other livestock

Extensive research has shown that black soldier fly larvae can be fed to chickens, pigs and fish as a replacement for conventional protein feeds such as soybean meal and fish meal. The American Association of Feed Control Officials, whose members regulate the sale and distribution of animal feeds in the US, has approved the larvae as feed for poultry, pigs and certain fish.

So far, however, there has been scant research on feeding black soldier fly larvae to cattle. This is important for several reasons. First, more than 14 million cattle and calves are fed grain or feed in the US. Second, cattle’s specialized digestive system may allow them to utilize black soldier fly larvae as feed more efficiently than other livestock.

Promising results in cattle

Early in 2022, our laboratory published results from the first trial of feeding black soldier fly larvae to cattle. We used cattle that had been surgically fitted with small, porthole-like devices called cannulas, which allowed us to study and analyze the animals’ rumens—the portion of their stomach that is primarily responsible for converting fiber feeds, such as grass and hay, into energy that they can use.

Cannulation is widely used to study digestion in cattle, sheep and goats, including the amount of methane they burp, which contributes to climate change. The procedure is carried out by veterinary professionals following strict protocols to protect the animals’ well-being.

RELATED: Seaweed May Be the Answer to the Burping Cow Problem

In our study, the cattle consumed a base diet of hay plus a protein supplement based on either black soldier fly larvae or conventional cattle industry protein feeds. We know that feeding cows a protein supplement along with grass or hay increases the amount of grass and hay they consume, so we hoped the insect-based supplement would have the same effect.

That was exactly what we observed: The insect-based protein supplement increased animals’ hay intake and digestion similarly to the conventional protein supplement. This indicates that black soldier fly larvae have potential as an alternative protein supplement for cattle.

Costs and byproducts

We have since conducted three additional trials evaluating black soldier fly larvae in cattle, including two funded by the US Department of Agriculture. We are especially interested in feeding cattle larvae that have had their fat removed. Data suggest that the fat can be converted to biodiesel, yielding two sustainable products from black soldier flies.

We are also studying how consuming the larvae will affect methane-producing microbes that live in cattle’s stomachs. If our current research on this question, which is scheduled for publication in the spring of 2023, indicates that consuming black soldier fly larvae can reduce the amount of methane cows produce, we hope it will motivate regulators to approve the larvae as cattle feed.

Economics also matter. How much will beef and dairy cattle producers pay for insect-based feed, and can the insects be raised at that price point? To begin answering these questions, we conducted an economic analysis of black soldier fly larvae for the US cattle industry, also published early in 2022.

We found that the larvae would be priced slightly higher than current protein sources normally fed to cattle, including soybean meal. This higher price reflects the superior nutritional profile of black soldier fly larvae. However, it is not yet known if the insect farming industry can grow black soldier fly larvae at this price point, or if cattle producers would pay it.

The global market for edible insects is growing quickly, and advocates contend that using insects as ingredients can make human and animal food more sustainable. In my view, the cattle feeding industry is an ideal market, and I hope to see further research that engages both insect and cattle producers.

Merritt Drewery is an assistant professor of animal science at Texas State University.

The post Opinion: Feeding Insects to Cows Could Make Meat and Dairy More Sustainable appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Meet the Modern Farmer Turning Manure Into Water appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>That’s what Donald DeJong thought to himself over and over, working on his farm, Natural Prairie Dairy, in the Texas Panhandle. From sourcing organic fertilizer and trucking it all over his acreage to dealing with weeds and issues with the lagoons that dotted his land, the whole system just seemed inefficient. It needed an overhaul.

DeJong has been a dairy farmer for more than 20 years, with the majority of that time focused on organic dairy. He and his wife started with 800 heads of cattle. Now, they have more than 3,500 cows and have expanded to a second ranch in Indiana. As his business kept growing, DeJong kept coming back to that thought: Is there a better way to do all of this?

“The biggest concern was how do we get a better source of organic fertilizer,” DeJong recalls. Like many dairy farmers, the DeJongs were using lagoons on their farm to safely hold the nitrogen and ammonia that naturally occur in the heaps of manure their cows produced on a daily basis. But letting all of that nitrogen literally evaporate into thin air was frustrating to DeJong. “That’s fertilizer. If we could figure out a way to capture that nitrogen, that was a big motivation.”

So, DeJong started looking around and found Sedron Technologies. Its Varcor system takes that manure and extracts the valuable nutrients, creating a steady stream of fertilizer and potable water at the same time. He flew to Washington to meet the team, where he found himself in a room full of engineers. “I was taken aback; there were over 20 engineers in that room. And we were talking about manure. I’ve never been in a place with that much brain power in one room, with the ability to say, ‘Let’s solve this,’” says DeJong, who signed on to act as a beta tester, putting the Varcor system to work on his farm.

While DeJong says the machinery can get a bit technical to run, with training, it’s easy to use. The manure goes in one end and water comes out the other. The process should be familiar to dairy farmers that use vapor compression to make dry milk powders.

“The liquid goes in, and we take the large fiber out, as there’s not a nutrition value or fertilizer value there. Then that liquid is heated almost to a boiling point,” explains DeJong, at which point condensation starts to collect. That vapor is captured and recompressed into liquids, creating one stream of distilled water and another of aqueous ammonia. The solids that are left over from the “bake” are a concentrated mix of phosphorus, nitrogen and potassium—the three key components of fertilizer.

Donald DeJong.

DeJong takes the dry powder and the aqueous ammonia, stabilized with ammonia nitrate, and uses it on his corn and alfalfa fields as concentrated, weed-free, organic fertilizer. In the face of ongoing fertilizer shortages, producing his own nitrogen has changed how DeJong approaches farming. “And then your clean water comes out, too. It’s beautiful clean water, and we’re upcycling all that stuff coming in,” he says. The farmer then uses the water to irrigate those same crops, creating a much more integrated system.

The Varcor system is a big piece of machinery, filling an entire tractor shed. It’s designed for at least a 3,500-head herd and can process about 110 gallons of input a minute. And with a machine that large comes an equally large price tag. DeJong says the initial investment is about $10 million, although he notes that it also comes with maintenance and tech support.