The post Staying ‘Fiber Curious’ in an Age of Fast Fashion appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Before the late 1970s, around 70 percent of the clothing that Americans bought was made in the country. As the world became increasingly globalized, this changed. Much of America’s clothing production was moved overseas. Today, most of the wool used in clothing comes from Australia. Synthetic fibers made from raw substances such as petroleum also extended the distance between local economies and natural fibers by offering a cheaper and faster alternative. Today, “fast fashion” results in far-reaching environmental and social impacts, such as exploited cheap labor and the use of harmful dyes and unsustainable fibers. What do we lose when we are removed from our fiber sources?

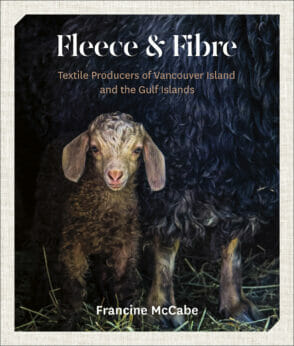

Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in British Columbia, Canada, have many artisanal textile farms. In her new book, Fleece & Fibre: Textile Producers of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, Francine McCabe takes you to them. Through thoughtful accounts of farm visits and original photos of charismatic animals, McCabe guides readers through the materials that are made in her region, as well as the farmers, plants and animals that produce them.

Beyond the individual farms, McCabe also paints a larger portrait of the textile landscape in Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. The area seemingly no longer has any processing mills for raw fibers. As a result, much of the material produced in the region has to leave to be processed, and it can’t be sourced by makers or artisans looking for local product.

In this book, which comes out October 10, McCabe digs into what it means to have a local and sustainable fiber economy and explores the confluence of industry and art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Modern Farmer: You begin the book with a quote from Indigenous writer and bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer: “To love a place is not enough. We must find ways to heal it.” Why did you choose this quote and how is this sentiment reflected in your book?

Francine McCabe: Everything she writes is wonderful and touches my heart. I read [that quote] while I was in the very early stages of researching for this book. And I just felt like that was the sentiment I wanted in this book. That was the through-line I wanted this book to have. I love Vancouver Island and I love the fiber economy we have here, and I would love to see it grow and be nurtured and for consumers to be more aware of what is going on in our fiber economy around us—and the importance of our textiles as a place-based symbol of where we come from.

Our textiles are gorgeous, that come from here. And it can be a way to showcase our beautiful land and our place. When I read that quote, it really spoke to me because I feel like if we can grow our fiber economy and we can nurture our textiles here, that is a way of us nurturing our land and taking care of the place we live.

Bluefaced Leicester X at New Wave Fibre. (Photography by Francine McCabe for Fleece & Fibre)

MF: You use a concept term in your book that might be new to many readers. What is a “fibershed”?

FM: I haven’t coined this term. It is from Rebecca Burgess, who is from California; she is the founder of the fibershed concept. But fibershed, technically, it’s the same as a watershed. It’s the place where you can get your raw materials, you can process those raw materials with transparency, in a specific way that is specific to that land, to that place. Each little pocket, each fibershed through our country, can produce the same breed of fiber, but it’s going to be different. It’s going to be processed differently, the feeling’s going to be different. So, a fibershed encompasses our raw materials, our makers [and] what’s specific to this region.

MF: The Coast Salish history of fiber work, before sheep were introduced to the area, was based on now-extinct Woolly dogs, mountain goats and many types of plant fiber. How can knowing the history of the fibershed inform the decisions we make as consumers?

FM: It was really neat to read a lot of that history because I had seen that there was a lot of fiber in our region that is no longer used because it wasn’t properly utilized. The processes of making it weren’t supported. So, now I see how much fiber we have here, and I want those fibers to be supported and utilized so that they don’t disappear. So, just to talk to some people about the Woolly dog and how much it was utilized and how it was the main fiber here and now it’s basically extinct…It’s pretty sad to hear. You don’t want those fibers that are specific to our region to disappear any further. So, I think that was really important to hear those stories and to really solidify the importance of processing our fiber locally, as much as we possibly can, using it, showcasing it.

Francine McCabe, author, “is a mixed-blood Anishinaabe writer, fibre artist, and organic master gardener from Batchewana First Nation, living on the unceded traditional territory of the Stz’uminus First Nation with her partner and two sons.” (Photo courtesy of Francine McCabe)

MF: You highlight an interesting discrepancy in your book between the amount of financial support and grants available for food-based agriculture and the lesser support for fiber-related farms. Why do you think this disparity exists?

FM: I think it’s maybe because all of our textile production has been moved overseas—out of sight, out of mind. So, people aren’t questioning it as much. The idea of transparency in our textiles hasn’t been brought [to] our attention as much as it has with food, even though food and fiber are both agricultural issues, they both start from the land and our dependence on the land and farmers. But I think that people just aren’t quite aware of it as much or we don’t consider it as much. Clothing and textiles are something we’ve kind of taken for granted as part of our surroundings, but they are just as impactful as our food that we are taking into our bodies.

MF: You set out to answer a pretty specific question—why is local fiber so costly to produce? You found your answer: no local mills. How would introducing more local infrastructure change the textile industry in Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands?

FM: There are people here who are interested in starting that, but the startup is extremely expensive. And there’s no government funding at this time, that’s like, ‘here’s the startup for a fiber-related business.’ So, a lot of people are struggling with just how to get funds to start that.

But if they were able to start that, every single farmer that I spoke to in this book said they would use a local fiber mill, if it was here. So, if there was somebody who had extra funds to start a fiber mill, they would be in business, and they would have years worth of fiber to process. If I had the money, I’d be all over that. And it would change our infrastructure because it would allow for a lot more of our fiber to be processed right here on the island, which would bring down the price for farmers. It opens up a bunch of different doors and a bunch of avenues for local businesses. It would be a huge boost for the economy.

Fleece from Gotland sheep. (Photography by Francine McCabe)

MF: You advocate that consumers demand the same transparency from our textiles as our food—we need to know what is in our textiles. What are some of the issues woven into mass-produced textiles?

FM: A lot of products that you buy that claim to be 100 percent natural [or] organic, the material may have been grown organically and the material itself might be 100 percent cotton, but then it’s finished with a finishing product that leaves a residue on the fiber that would never allow that fiber to break back down into the soil. So, yes, the fiber itself is natural and organic, but the chemicals in the process that they’re using to dye it and to treat it is not organic.

It’s one of those confusing things, as it is with food. Like “organic”—what does that really mean anymore? And so with our clothing, it’s the same thing. They say things on them, like “ethically sourced,” but what does what do those words really mean? For us as consumers to just demand from our brands, what does that mean? What does ethically sourced mean for you? And who’s making your products? Where’s the material coming from? Just more questions we could be putting onto the brands so that they feel the need to have more transparency.

Yarn being dyed at Hinterland Yarn. (Photography by Francine McCabe for Fleece & Fibre)

MF: In reporting for this book, you visited several different farms, spoke with a lot of innovative people and met many photogenic animals. I’m sure they all stand out in their own unique ways. What specific highlights or takeaways will stick with you?

FM: I got to meet the Valais Blacknose breed [of sheep], which was one of the breeds I really wanted to meet. And they were just as cute as I expected them to be, and friendly, so that was great. But I think really just being able to see the farmers and see their actual passion for the fiber solidified that this book was where I really wanted to go, because I wanted to help them pass their message along and wanted to connect them to other makers.

MF: You encourage readers to stay “fiber curious.” What does that mean to you?

FM: When you go to purchase products, maybe look at your tag, see what they say, just look for local stuff. If you’re thinking you want a new sweater, maybe get curious who’s making sweaters in your 15-mile radius around you and see if those are the types of sweaters you might want, versus going out to the store to buy one. Just stay curious about what is happening with your textiles [and] where they’re coming from. Think about them as you would your food.

We are at a time in this world where it’s important to consider all of these different avenues, not just our food. And maybe it’s time to change how we produce and consume our textiles, as well. I think it’s just important that people realize that our textiles are an agricultural product. We are depending on farmers and the land for these things, as much as we are our food.

The post Staying ‘Fiber Curious’ in an Age of Fast Fashion appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Goldilocks Zone Needed to Keep Strawberry Fields Forever appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>But that could change. A report released this spring by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) suggested that, by 2050, unless growers move north, there’s a real possibility that there will be no Florida strawberries on grocery store shelves during those crucial winter months. “By mid-century, Hillsborough County will no longer be within that Goldilocks range,” says Dr. Eileen McLellan, a senior scientist at EDF and co-author of the report.

In 2020, there were approximately 75 days with temperatures over 85 degrees Fahrenheit in Hillsborough County. By 2050, the climate models used by the EDF predict that number could soar to more than 150 days. It’s already getting hotter. The 12-month average temperature in the county has increased by 4.9 degrees Fahrenheit from May 1900 to April 2023.

Photography courtesy of Canadian Berry Trial Network.

Outside of Florida, which produces many of the winter strawberries, the majority of the strawberries in the nation come from California. The golden state produces 87 percent of all the strawberries consumed in North America. Are strawberries doomed here as well? Scientists at the University of California (UC), Davis have been researching and developing new varieties of strawberries since the 1930s. “One of the primary concerns for growers in California, at the moment, is the saline content in water and soil,” says Dr. Mitchell Feldman, director-elect of UC Davis Strawberry Breeding Program and Research Group.

Too much salt in the soil will, over time, pull water out of plant roots and cause them to die. Salt is present in all soil and is normally leached away by rain or through irrigation. But, up until the heavy rains of last winter, more than 60 percent of California was in the grips of a drought that scientists say was made more severe because of human-caused climate change. The salt in the soil remained. Drought may be one side effect of climate change, but it’s not the only one with which growers are contending. A warmer atmosphere has an increased ability to hold moisture, which causes heavier and longer periods of rain. This means unpredictability for growers.

“No two seasons are the same anymore,” says Kevin Schooley, executive director of the North American Strawberry Growers Association. “Some growing periods are wet; others hot and dry. But it’s the crusher events, periods of unexpected and heavy rain, and sudden storms that do the real damage.”

The heavy rains in California last winter may have ended a long period of drought, but they also caused strawberry fields to be flooded. This meant fewer strawberries available at the grocery store, along with higher prices. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of strawberries in the United States during the first week of March 2023 was 27 percent higher compared to the same time in 2022.

Photography courtesy of Canadian Berry Trial Network.

A warming planet also encourages the spread of soil pathogens. Fusarium wilt is a fungal infection that attacks plant roots and also restricts water flow through the plant. Once controlled by methyl bromide, a pesticide now banned because of its harm to the atmosphere, fusarium wilt thrives in high temperatures, arid climates and warm soils.

“California is a perfect storm of heat and dry [conditions] for soil pathogens to emerge,” says Dr. Stephen Knapp, director of the UC Davis strawberry breeding program. This past spring, UC Davis released five new strains of strawberries into commercial production resistant to fusarium wilt: UC Eclipse, UC Golden Gate, UC Keystone, UC Monarch and UC Surfline.

Three new varieties of strawberries have also been developed recently by the Canadian Berry Trial Network (CBTN), spearheaded by Dr. Beatrice Amyotte, and have proven more resilient to the effects of climate change than those previously grown in eastern Canada. “Their skin is cohesive, airtight and watertight, which makes them able to withstand heavy precipitation without becoming soft or broken up by the rain,” Amyotte told Canada’s Weather Network.

The Canadian Berry Trial Network team.

It takes time, though, to develop new varieties of berries. It took Amyotte and her team 10 years to produce those three varieties. With the effects of climate change affecting the planet faster than first predicted, will there be enough time to save the strawberry? An international team of scientists led by UC Davis has been able to sequence the genome of the cultivated strawberry. This genetic roadmap makes it easier and faster to target specific traits and develop the strawberry with climate change-resistant qualities, such as a higher saline resistance in the event of drought.

Even in the field, growers are finding creative ways to adapt. “Polyurethane tunnels and cloth covers are regularly used to shade plants from extreme heat and severe weather. It’s amazing, even with the sides of the tunnel pulled up, it stays cool,” says Schooley.

McLellan is realistic that strawberries may not be able to be grown in the fields of Hillsborough County by 2050, but she is also hopeful about the berry’s future.

“Strawberries are a bellwether of what could happen to other small berry fruits and vegetables as climate change marches on,” says McLellan, “and why it’s important to study them now and make important changes before it does become too late.”

The post The Goldilocks Zone Needed to Keep Strawberry Fields Forever appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post How the Haskap Berry Survives Arctic Temperatures appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>With only 88 farms producing just one percent of the fresh produce consumed locally, it’s not a choice but a necessity for food to be imported from the south. Until now. North of the capital Whitehorse, in the southernmost part of the territory, Yukon Berry Farms is growing 50,000 haskap berry plants on 50 acres.

In 2022, the farm yielded 15,000 pounds of berries, most of which will be turned into wine or cider and exported out of the territory—a rarity for the area, which is almost completely reliant on imported food.

It begs the question: How can haskaps be grown on such a massive scale, in such an inhospitable setting?

Photography courtesy of Yukon Berry Farms.

Haskaps, which look like an elongated blueberry and taste similar to a tart raspberry, grow wild in circumpolar regions throughout Canada, Asia and northern Europe. But very few people have heard of them.

“Wild haskaps are small and it takes a lot of picking to fill a bucket,” says Dr. Bob Bors, manager of the fruit program at the University of Saskatchewan. There, Bors has successfully hybridized more than 10 different varieties of haskaps, all suited for northern growing.

The idea of turning haskaps into a commercial crop first took seed in the 1950s. Canadian horticulturists hybridized a strain of haskap from wild plants and those commercially grown in Siberia. But it didn’t even make it to market. “That berry,” says Bors, “tasted like tonic water and fruit breeders saw no marketability in it.” Bors’ secret weapon was the sweet Japanese haskap, which he combined with the Canadian wild berry and Siberian cultivator to create a cold hardy plant, with a bigger, tastier fruit than earlier versions.

Now his berries are growing at Yukon Berry Farms. He’s not surprised at their success, especially with climate change causing warmer winters. In 2021, the lowest recorded temperature in Whitehorse was -45.5 degrees Celsuis. Further south in Abbotsford, the heart of British Columbia’s fertile berry-producing Fraser Valley, where mild winters are often the norm and spring comes early, the temperature barely dipped below -7 degrees Celsius.

“Haskaps love extended periods of deep, sub-zero cold,” says Bors. “In the south,they can wake up too earl, and flower before the bees and insects they rely on for pollination and ultimately fruit production have broken their hibernation.” Bors’ research also suggests that the heat typical of long southern summers could shut down the plant’s ability to grow and produce.

They’re also susceptible to humidity. “This can cause powdery mildew, a fungal disease, that damages the plant,” says Graham Gambles, secretary for the Haskap Berry Growers Association of Ontario. This makes Whitehorse’s dry climate (it receives less than 260 millimetres of rain, or 11 inches, annually) ideal for haskaps.

Photography courtesy of Yukon Berry Farms.

Kyle Marchuk, the co-owner of Yukon Berry Farms, knew how lucrative haskaps could be as an export crop from the moment he first encountered them.

“A friend of mine was growing haskaps on a small test plot, here in the Yukon, and they were producing more berries than on bushes being grown in the south. So many, in fact, that a buyer from outside of the Yukon was willing to buy all the berries that could be produced and export them out of the territory.”

It spurred Marchuk to become a partner in Yukon Berry Farms in 2014 and plant 20,000 haskaps. In 2016, at a food show in Tokyo, Japan, he showcased haskap berry jam and was amazed at the Japanese interest in the product. He knew then that haskaps could be a lucrative export market for Yukon growers.

By the end of 2018, Yukon Berry Farms had expanded operations and was growing more than 40,000 haskap bushes.

Photography courtesy of Yukon Berry Farms.

There are weeds that pop up between the plants and voles that eat the bark for food over the winter. “But the biggest challenge,” says Marchuk, “has been the changes the Canadian government made in 2019 to export licensing of fresh food.”

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s (CIFA) new regulations meant growers such as Marchuk would be required to do more paperwork and be subject to more inspections. The process was more time consuming than it had been and the licensing more expensive, so instead of exporting raw berries and jam, Marchuk and his partners opened Yukon’s first winery and cidery.

“The laws surrounding the export of alcohol are more lenient. We’re exporting haskap wine and cider to Japan and planning to get products into stores across Canada very soon,” he says.

Taking three to four years to reach maturity, each haskap bush can yield up to 10 pounds of berries a season—enough to share with the world and the local community, says Carl Burgess, executive director of the Yukon Agricultural Association. He sees no reason why haskap berries grown in the Yukon can’t be exported. “We have tomatoes from Mexico imported to the Yukon, so why not locally grown haskaps exported to Mexico?”

The post How the Haskap Berry Survives Arctic Temperatures appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Bringing Hazelnuts Back from the Brink appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>It was the winter of 2014 and Andres, like many other hazelnut growers in the Fraser Valley region of British Columbia, was destroying the last of his hazelnut trees lost to Eastern Filbert Blight. Burning is the best way to remove infected trees, according to guidelines from B.C.’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries. Still, it was an emotional experience for Andres. “Getting rid of the old trees…it took a lot of tears.”

Peter Andres burned his hazelnut trees at his former farm in Agassiz, BC. Photography courtesy of Peter Andres.

Eastern Filbert Blight, a fungal disease spread by windblown spores that ultimately destroys infected trees, had spread from the east to west coast of North America in the late 1960s, initially into Washington and Oregon, then eventually into BC. The blight was first detected in BC in 2002; immediately, it was a race against the clock to slow its spread. Andres, then president of the BC Hazelnut Growers Association, worked with a team of growers to map impacted farms, trying to predict which would be hit next. They monitored orchards for symptoms and cut down infected trees. But as the fungus kills trees from the inside out for at least a year before they show symptoms, it was a losing battle.

The goal then shifted to securing a supply of blight-resistant trees for replanting. By the time the fungus reached BC, Oregon State University had already been breeding blight-resistant varieties for more than three decades in an effort to save Oregon’s official state nut. A quarantine was put in place by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) in 1975 to try to keep the disease out of BC. But the quarantine also prevented the import of these new blight-resistant trees from coming into the country. It took several years, but Andres and other growers were finally given the green light to bring tree tissue culture across the border in sterile test tubes. Using this culture, trees were cloned in a lab and raised by Nature Tech Nursery until ready to plant. Andres’ orchard was among the first in BC to trial the new varieties in 2011.

Rows of blight-resistant trees on Andres’s farm. Photography by Peter Andres.

Despite these efforts, the blight decimated the BC hazelnut industry. Hazelnut production declined from more than one million pounds pre-blight to around 25,000 pounds by 2017, a loss of nearly 98 percent. Andres recalls walking politicians through ravaged hazelnut orchards, making a case for government financial support to help keep the industry alive. “It’s about food security,” he explained at the time. As Andres notes, hazelnuts are the only nut grown commercially in BC, which produces approximately 90 percent Canada’s hazelnuts.

After six years, the BC hazelnut industry is finally in a period of renewal. After an initial push to attract new growers and expand the number of acres planted, and with support through the BC Hazelnut Renewal Program launched in 2018, hazelnut production is steadily increasing. The new varieties from Oregon have proven not only blight resistant but also higher yielding. “We’ve got nuts rolling off the fields,” says Zachary Fleming, president of the BC Hazelnut Growers Association. In 2021, BC produced more than 70,000 pounds of hazelnuts on around 350 acres. He’s hopeful that BC will be able to meet, if not surpass, pre-blight production levels within a decade.

The BC hazelnut industry is not a significant player in global production, nor does it wish to be. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Turkey is the largest supplier of hazelnuts, accounting for 62 percent of global production in 2020, followed by Italy and the United States. In North America, most hazelnuts are produced in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, with some production in Washington and BC. Oregon accounts for around 5 percent of the global production with nearly 100,000 acres planted (68,000 bearing acres in 2022). In comparison, BC hopes to reach 1,000 acres.

Photography by Peter Andres.

Ferrero Group, which makes Nutella, Ferrero Rocher and Kinder Surprise, buys around a quarter of the hazelnuts grown globally and has been looking at Canada to diversify its suppliers. While the BC Hazelnut Growers Association is open to the idea of supplying to Ferrero in the future, its focus for now is the local market. As Fleming explains, “There is enough global supply, so we aren’t looking to be a huge exporter. We want to produce BC products for BC.”

Fleming estimates that there are now around 100 growers in BC, and most of them are new. “There are a few [industry] pioneers out there who have replanted, perhaps less than five,” says Fleming. “It’s been a complete restart… so there’s a generational knowledge gap.” This knowledge gap is compounded by having to work with new varieties, which Fleming says might as well be entirely different species. “The first field I helped plant was five years ago, and we’ve made five years of mistakes.”

In addition to replanting, the lack of processing capacity was another hurdle faced by the BC hazelnut industry. With the supply of hazelnuts having dried up, the two former processing facilities in the Fraser Valley were forced to shut down. The call was answered by the Hooge family of Fraser Valley Hazelnuts Ltd. The property purchased by the family to expand its poultry production happened to be the site of a former processing facility. “All the growers that had replanted came to us and said ‘hey, can you start it up again?”recalls Kevin Hooge. “The whole future of the industry seemed to hinge on that decision.” So, the family dusted off the old equipment and got to work, gradually expanding its operation into a full processing facility that now services the entire BC hazelnut industry. Since opening in 2016, the plant has played a vital role in helping new and existing farmers get their hazelnuts to local customers.

Peter Andres at his local farmer’s market. Photography courtesy of Peter Andres.

After clearing his fields, Andres needed a fresh start. In 2016, he purchased a new farm where he planted blight-resistant trees. Eager to pass on his nearly four decades of knowledge to the next generation of growers, Andres helped form the Hazelnut Growers Collective. Today, Andres can be found at the Vancouver Farmers Market selling hazelnuts under the banner of the Hazelnut Growers Collective. He first sold hazelnuts at the market out of the back of his pickup truck on a busy Thanksgiving weekend in 1997. After the blight hit his farm, Peter thought he would have to say goodbye to his market customers forever. Through the collective, growers co-ordinate their market attendance, prices and packaging. This means that their customers have a reliable supply, while allowing the growers greater flexibility.

The renewal of the BC hazelnut industry has required persevering farmers, enterprising processors, teams of researchers, cross-border collaborations and government support. Andres reflects on the last 15 tumultuous years “People always ask me, ‘Aren’t you sad that all your trees died?’ I’m sad, but in a way, I’m not sorry. Instead of us old fogies with the old farms and old varieties, we now have new ones. The industry got reinvigorated.”

The post Bringing Hazelnuts Back from the Brink appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Farmer by Day, Rockstar by Night. How Del Barber Jumps Between Two Worlds appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>It’s that sense of reflection that carries through Barber’s seventh studio album, Almanac. While it might seem like a love song about a person, it’s actually written for his home: specifically, the farm and ranch he shares with his wife and family in rural Manitoba. When Barber isn’t touring with his band or in the studio recording music, he’s working the 2,000-acre farm with cattle, chickens, row crops and cut flowers.

Barber with his family on the farm. Photo submitted.

It can be difficult to balance his two lives: that of an award-winning musician who tours through the US and Canada regularly, and that of a farmer and rancher with a working farm and business. “Over the years, I’ve developed a relationship where I can come and go from the farm…I pick particular jobs on the farm and commit to doing them,” says Barber. For instance, he’s the designated fence guy—each spring, he’ll fence all the pastures. Whether he’s touring or home, he’ll schedule that work in, so everyone else can focus on the day-to-day.

The work also helps Barber write his music; the repetitive nature of farming acting as a sort of meditative process. “During harvest time, I’m hauling grain, or I’m in the combine and I don’t have anyone else around. My mind immediately starts to work on songs,” says Barber. “In terms of the music, it’s a symbiotic relationship. I get to do something completely different. It’s physical, it’s outside and it gives me something to write about.”

Del Barber. Photo submitted.

It also keeps him humble. Sure, as Barber will tell you, he may not have the star power of a Chris Stapleton or a Maren Morris, but performing music for applauding audiences doesn’t have much in common with shoveling cow manure or weeding the garden beds. “I definitely feel like there’s a distinct wake-up call every time I come home and have to go back to the farm,” says Barber. “Sometimes, music seems like a really important pursuit. And other times, when you watch a calf that you’ve been trying to keep alive for a week, in the ice and snow, and it dies—It gives me perspective on my own life and career and it makes me realize that I’m pretty small potatoes.”

Despite that occasional self-deprecation, Barber does strive to forge connections in his music, particularly bridging the divide between urban and rural communities. “I want to celebrate rural life and dispel some of the myths of it,” says Barber. “I want to tell the truth about my experience, the good and the bad, and try to make the conversation between urban and rural people have an ounce of nuance. Oftentimes, I just feel like it’s just so politicized, especially in the United States. I just feel like so often, both parties just don’t understand each other.”

Despite his efforts to bring those two communities closer together now, Barber didn’t grow up on a farm. He grew up in a suburban town just on the edge of Winnipeg, in the center of Canada, but he was always drawn to farm life. His first jobs were as farm laborer on u-pick strawberry farms and driver for grain farmers. He started working harvests on big farms close to the border with North Dakota. And, through all of this, he was playing in bands and writing songs. They all touched on rural life, from his debut Where The City Ends in 2010 to 2014’s Prairieography, which netted him Songwriter of the Year at the Western Canadian Music Awards.

Barber’s talent is in noticing and highlighting the granular—the small details that make up his everyday life—cooking for his family, tending to the cows, clearing pasture. These are what make his songs resonate. That’s why the title Almanac works so well for the latest album. The songs are both a record of how life is now and a prediction for the future. “[Almanacs] are informed by history. Predictions are informed by what’s happened before, and I think good music does that as well.”

The post Farmer by Day, Rockstar by Night. How Del Barber Jumps Between Two Worlds appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Meet the Dumpster-Diving Chef Who Turns Food Waste Into Jam appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>Working in restaurant kitchens for 17 years—he started at age 15 and worked his way up to chef, winning the first season of Radio Canada’s Les Chefs!—and always up for an epicurean challenge, Cantin (literally) dove into the adventure with relish when his friend, Thibault Renouf, suggested the idea in 2016.

“I went behind a grocery store and jumped into the dumpsters,” says Cantin. “I wasn’t surprised as much by the quantity of food I found, but I was surprised by the quality. If something isn’t edible, it’s understandable to throw it away, but what we found was beautiful food, still in the package.”

Cantin won the dare with gusto. From two dumpsters at separate grocery stores, he found so much quality food that he was able to prepare nearly 100 meals. Since there was an abundance of fruits and vegetables, the menu Cantin created reflected the bounty. He prepared a red pepper soup that was garnished with spicy hummus and small dices of orange, red and yellow peppers. For the main course, the duo served roasted lettuce with a lettuce cream, quinoa, pomegranate and sage. And for dessert, he made a pan seared “pain perdu” (a type of bread pudding) with coffee-cumin yogurt and slices of yellow plums.

It was a veritable feast, sourced from two dumpsters.

Red pepper soup, part of the first meal Cantin made with ingredients found in a dumpster. Photography by Fabrice Gaëtan.

That first dive into a dumpster opened Cantin’s eyes. Shortly thereafter, Cantin and Renouf sat down to more deeply investigate the food supply chain they thought they knew. With the addition of two other friends, Bobby Grégoire and Marie Gaucher, the appropriately named La Transformerie was born. Transformation. The non-profit started up in July of 2017 with a fact-finding mission, beginning by speaking with employees at grocery stores: What had they tried in the past to reduce food waste? What is the reality?

“They were very open with us because they saw we weren’t judging them; we just wanted to figure out a solution.” The goal of La Transformerie was to reduce food waste by using quality unsold food to help those in need.

The impact so far is massive. Cantin’s dive into a dumpster led to a company that takes food waste from grocers, donates 67 percent of it to food banks, composts any unusable items (about 7 percent) and then preserves and sells the rest back to the consumer. By partnering directly with grocers, Cantin saves himself a jump into the dumpster, and the grocers get positive marketing and an opportunity to show their employees that they’re doing the right thing.

Growing steadily since 2017, La Transformerie now has contracts with 17 grocers, from small independent stores to large local chains. They utilize a network of 1,200 volunteers who collect the food each week and help with distribution and processing. Once the food is picked up, it’s organized by type, then measured and cleaned. The largest portion is donated to food banks including any meat, bakery items, eggs or dairy. As the group gets more popular, it sometimes has two pickups per week.

“The grocers know we’re there to help them, so they see we’re serious—because of this, the partnerships are going well,” says Cantin.

Chef Guillaume Cantin. Photography by Thanh Pham.

The group has donated and repurposed 160,000 kilograms (nearly 352,740 pounds) of produce since 2019. Anything that doesn’t get donated or tossed out is put to use in its Les Rescapés (the survivors) line of marmalades, jams and sauces. Cantin makes an average of 800 jars a week, which are then sold at dozens of specialty food shops and grocers.

Although he’d worked as a chef for many years, canning was a new process, so Cantin took training classes to learn about preservation techniques. Now, he creates original recipes using the ingredients donated by the grocers. All of the Les Rescapés products are made using minimal ingredients and they are vegan and low in sugar.

People are surprised by the quality of the products, says Cantin, and that’s the goal. He wants to showcase that unsold food is still quality produce. “People think it’ll have mold or be inedible, but in reality, there may sometimes be a brown mark that needs to be cut off, but, otherwise, it’s ripe and beautiful—the perfect time to transform it and showcase the quality.”

Working out of the basement of a former church, Cantin created a lab and test kitchen. He keeps samples from each batch of jam and marmalade produced, and he is able to experiment with flavors based on the donated produce. The group currently has an abundance of apples, so it is featuring two apple products. It often receives tomatoes, so Cantin developed a barbecue sauce. The products are dependent on the unsold produce, so the group will often have an abundance of one item but a shortage of something such as grapefruit for the marmalade. Still, there are always seven or more varieties available at all times.

Although the four friends have made a huge dent in food waste in just a few years, Cantin says they always try to push themselves. Right now, they’re planning a limited-edition preserve using blueberries while they’re in abundance. They’re also working on a new project to educate organizations about food waste and what they can do to initiate change.

“We love food so much that we want to make sure everyone else is falling in love with food. Plus, we want to erase food waste, especially when there are those who aren’t eating enough.”

With the help of friends, volunteers and grocers, Cantin is finding a way to meet these goals. No dumpster diving required.

The post Meet the Dumpster-Diving Chef Who Turns Food Waste Into Jam appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post The Ebbing Tide of Dulse appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>With a population of approximately 2,700, almost everyone on the island has dulsed. Your parents or grandparents were dulsers, you’ve harvested or you know someone who does. It’s one of the Island’s identifiers. But there have been changes recently. “There are good years and bad,” says Bonnie Morse, mayor of Grand Manan. “Dulse isn’t as reliable as it once was.”

Photography courtesy of Noah Leonard.

Located at the entrance of the Bay of Fundy, the island of Grand Manan is a 90-minute ferry ride from New Brunswick’s mainland. Everything on the tiny 24-kilometre-long enclave depends on the sea. In bad weather, the ferry doesn’t come. When the water is calm, tourists arrive to marvel at panoramic ocean views and tiny hamlets where, like in the old days, no one locks their door at night. It creates a protectiveness in islanders towards what the sea provides — especially the dulse. There’s also lobster, herring, scallops and crab to supply Grand Mananers with a steady ocean diet.

Most people outside of Canada’s maritime provinces have never heard of or tasted dulse, the chewy, umami-tasting purple seaweed with an ocean smell. A 21st-century superfood, dulse contains high concentrations of iodine and is loaded with vitamins B, C and A, potassium and calcium. The purity and quality of Grand Manan dulse is sought after by nutraceutical and vitamin manufacturers. On Grand Manan, dulse is added to chowders, stews and pretty much everything in between. Growing in the lower intertidal zones of the North Pacific and Atlantic oceans, it’s one of the world’s oldest foods. Monks on Scotland’s Island of Iona ate it 1,400 years ago. In Iceland, it’s called söl and is a source of dietary fibre. But ask any self-respecting Grand Mananer and they’ll say their dulse is the world’s best. Matthew Abbott of the Conservation Council of New Brunswick credits the tide. “It gives dulse its Grand Manan edge.”

Bay of Fundy tides are the strongest in the world. At peak flood, the water rushing past Grand Manan is 25 million cubic meters per second. The sheer force churns up the seabed, feeding the dulse a steady diet of minerals and nutrients. At low tide on the west side of the island, 200-foot cliffs cast shadows that shade the dulse from the sun and bleach out all that tidal goodness. They’ve been dulse’s secret ingredient — until now.

Typically harvested between June and October, dulse is a finicky crop. It needs a water temperature of between 5 and 14 degrees Celsius to reproduce. The Bay of Fundy averages between 5 and 12 Celsius. But for how long? Climate change is not only heating the atmosphere but the ocean. In 2021, temperatures in the Bay of Fundy were 2.3 degrees above average. “It’s terribly unfortunate,” says Abbot. “It’s the fastest-warming water on the planet.”

But it’s the rock rollers, as Grand Mananers call them, that really do damage. Violent storms cause the sea to overturn the rocks into which the dulse is suckered and ripped to shreds. Climate change has altered weather patterns and once-in-a-decade storms are seemingly yearly now. The slow-growing dulse can’t recover between volleys.

Abbot’s job is to look for ways to protect the shoreline from the ocean’s powerful churn. “There are environmental impact studies and research to be done, but artificial reefs anchoring the dulse in place and preventing a rock roller from doing harm is one idea.”

Atlantic Mariculture, a Grand Manan company that provides dulsers with a market for their haul, is also looking for solutions. Jay J. Botes, marketing and communications lead for the company, says that if the natural environment was too inhospitable for dulse, they may be able to grow it indoors. “I would expect to see dulse being cultivated in land tanks that could mimic the conditions of the wild.”

As conditions change along Grand Manan, Atlantic Mariculture has had to diversify its product line. Popular sea vegetables such as rockweed and nori also cling to Grand Manan’s shores. They are slightly less dependent upon location and water temperature, giving the company a more dependable crop and opportunity for harvesters.

Photography courtesy of Noah Leonard

Grand Mananers have been through this type of decline before. The herring industry used to employ Grand Mananers, says Morse, but when it declined, it was lobster and dulse that anchored people.

“People stayed. They built a life, had children and retired on dulse,” says Morse. “This generation doesn’t see dulsing as a viable career. They’re turning to the mainland for jobs or the more lucrative lobster fishery. They harvest now to supplement other income.”

Morse hopes this will be a good year for dulse. There weren’t rock rollers this winter and the water is cold. The dories still come and go from Grand Manan. But for how long?

The post The Ebbing Tide of Dulse appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The post Farmworkers in Canada Hack Menus, Protest for Better Labor Conditions appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>The Migrant Workers Alliance for Change has tagged tables in hundreds of restaurants in Ottawa, Toronto and surrounding areas with large political offices with the codes. The codes appear to be menus; but upon first scan, they instead showcase the exploitative working conditions faced by many foreign farm workers.

The “To-Die-For Sweet Potato Fries” item, for example, tells the tale of a potato harvester from Jamaica named Garvin Yapp who was killed in a farming accident in southern Ontario last summer. The “Bitter Strawberry Tart” explains the 18-hour days some workers spend harvesting strawberries on their hands and knees—most of the time under the hot summer sun. Those who come in contact with these secret menus are also directed to a petition that calls on the Canadian government to provide better labor conditions for migrant workers and to grant them permanent resident status.

Robert, a greenhouse worker from Jamaica who has been in Canada for the past seven years with temporary resident status, is no stranger to such conditions. He tells Modern Farmer he hasn’t had a day off since the pandemic began in 2020. He came to work on Canadian farms in hopes of building a better life for himself.

“The moment I got off the plane, it didn’t take long to realize all of our rights were taken, our rights have been forgotten,” he says. “We do what [the employer] wants us to do. We can’t say no because the moment we stand up to say no… I will be told that I can go home, back to where I came from.”

Robert has seen cases where injured workers were prevented from going to the hospital because businesses were worried about the visit raising the price of their insurance. He’s spent long days with fellow workers in unventilated greenhouses, where the air is thick and pesticide-ridden.

“I had problems breathing. I had coworkers with constant headaches. Sometimes, you have people throwing up, blood coming out from their nostrils,” Robert recalls.

The Migrant Workers Alliance for Change has documented these issues and other examples where farmworkers say their employers subjected them to crowded, substandard housing, long hours and unsafe working conditions that threaten their health. And those who want to raise concerns, like Robert indicated, fear they will be deported or barred from coming back into the country. Canadian studies have also illustrated the bleak reality of these conditions where, between January 2020 and June 2021, nine migrant agricultural workers died in Ontario.

Workers like Robert believe permanent residency status will help them better assert their rights, grant them access to social services such as health care without the permission of their employer and allow many workers to reunite with their families in Canada. Prime Minister Trudeau promised a change in status for all temporary foreign workers in his 2021 immigration policy priorities.

Canada brings in more than 60,000 seasonal agricultural workers each year, under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), which allows Canadian employers to hire temporary migrant workers from Mexico and 11 countries in the Caribbean.

Photography courtesy of Migrant Workers Alliance for Change.

As politicians headed back to the House of Commons in Ottawa at the end of January, organizer Luisa Ortiz-Garza says it was the perfect opportunity to launch the campaign and get attention from both civilians and politicians.

“We thought, what better way of making people part of our fight than showing them what it takes for the food to reach their tables while they’re at the table—the hidden cost,” she says. “What we are really saying is that our workers need equal rights and deserve to live a dignified life with their families.”

Ortiz-Garza says the response to the campaign has been overwhelming. The group has garnered thousands of signatures since the initiative began in late January. She notes, however, that momentum is building and QR stickers will eventually be plastered inside the country’s east and west coast provinces over the next few weeks. The organization says they will continue to campaign until the Canadian government fulfills its promise. It is planning to hold an event this weekend and another one in late March, centering around the secret menu initiative and its request for permanent residency. Ortiz-Garza says details would be published on the organization’s website in the near future.

As for Robert, regardless of how successful the campaign ends up being, he says he will continue to find ways to speak up and speak out.

“I’m never going to be tired of telling my story, until the world knows what migrant workers are faced with,” he says. “If people are enjoying a cucumber or a pepper and it comes from Canada, I am one of the persons who helped to have that get to their table. I hope at least they think about the people on the ground who make this happen.”

The post Farmworkers in Canada Hack Menus, Protest for Better Labor Conditions appeared first on Modern Farmer.

]]>