From water sensors to weather stations, farm hacking takes off.

Steve Spence, an amateur organic farmer in Andrew, South Carolina, has a smart way of irrigating his vegetables. He uses water from his pond and the fish waste to fertilize his plants, a technique known as aquaponics. But the critical balance between the makeup of the water and soil means Spence has to know exactly what’s going on in both. Real-time information about the pond’s make up is imperative to know he’s giving his veggies the best drink of water.

Sensors are commercially available, but Spence found them too expensive and not nearly as flexible as he needed – “they can only do the function you purchased them for.” So he decided to customize his own. Now he monitors the water’s pH, temperature and ammonia levels, along with soil temperature, moisture levels and barometric pressure, all from a system he built himself – on the cheap.

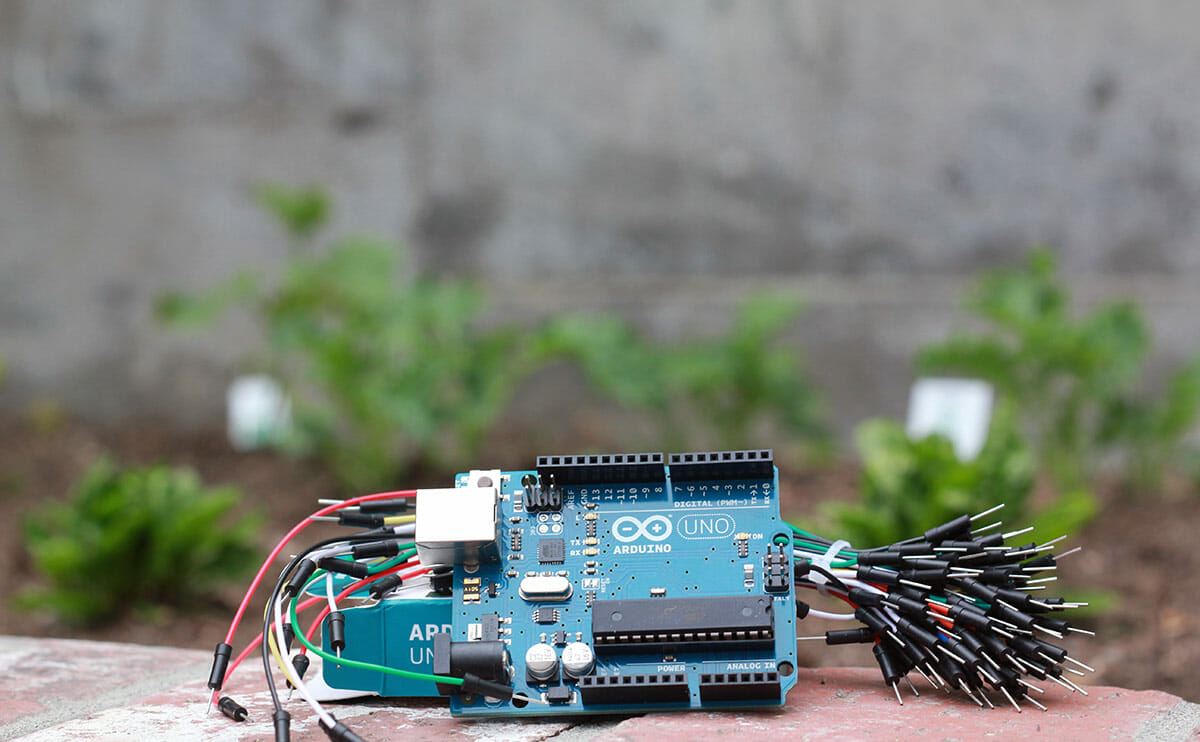

This is what happens when maker culture – specifically, projects made using the popular, flexible Arduino boards – comes to the farm and garden. From aquaponics to weather stations, farmers are starting to embrace the modern trends of DIY tech.

Arduino boards are perhaps the world’s best known amateur microcontroller – cracker-sized circuit boards that cost about $30 and, say, govern the intake of information or the actions of a motor. They come with customizable inputs that both receive information (like Spence’s sensors) and generate it, like giving commands to a device. Garage innovators employ them to control gizmos that remotely unlock doors or automatically feed the dogs when they’re away. Now, Arduino boards are creeping into amateur and professional agriculture to streamline and cheapen operations.

Ben Shute runs Hearty Roots Community Farm which has a CSA for the Hudson Valley and New York City. When he was starting out, Shute rented greenhouses but they were a lengthy trip from his land. Due to faulty old ventilation equipment, they would unexpectedly heat up, forcing Shute to make the long drive to ensure everything wasn’t turning tropical. So Shute worked with Louis Thiery, a Boston-based engineer, who wrote up the instructions to build an Arduino-based sensor system called “Fido,” which would alert Shute via text message each time temperatures hit those thresholds, all for around $125.

[mf_list_sidebar layout=”basic” bordertop=”yes” title=”Five Farm Hacks” separator=”yes”]

[mf_list_sidebar_item itemtitle=”Automatic Chicken Coop Doors”]Your chickens can finally experience the same comfort and ease you get when walking into the grocery store, thanks to automatically opening and closing chicken coop doors.[/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[mf_list_sidebar_item itemtitle=”Garduino”]Use an Arduino board to build a computer to run your whole garden. Kind of like HAL from 2001, except (knock on wood) it won’t try to kill you.[/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[mf_list_sidebar_item itemtitle=”Temperature Logger”]Know exactly how hot and how cold your plants are getting with this dead-simple temperature logger.[/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[mf_list_sidebar_item itemtitle=”Hook Your Plants Up to Twitter”]Measure soil moisture for your favorite plant. When it gets dry, it’ll tweet at you. ‘Need water, am very thirsty please RT and fav.'[/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[mf_list_sidebar_item itemtitle=”DIY Weather Station”]Measure humidity, wind speed, rainfall and become your own weatherman. Not included: green screen and ugly blazer and tie.[/mf_list_sidebar_item]

[/mf_list_sidebar]

“It’s hard to say how much money I’ve saved; if it’s just saved me from one disaster, that’s thousands of dollars,” Shute says. “But it’s also saved me a lot of anxiety.”

The idea of programming a microcontroller can, at first, seem daunting – a tiny plate packed with knobs, holes and ports that do God knows what. Yet, you don’t need a degree in computer science or electrical engineering to use Arduino boards, just a little patience to learn the logic and language. (This journalist has neither, and tinkers with them.) The software – written in C, one of the most common programming languages – that controls them is free and open source, meaning anyone can change it to suit their needs. But in most instances, coding a sensor is just a copy and paste job of someone else’s work.

Shute founded Farm Hack, a site designed to bring together farmers and engineers, since as simple as Arduino can be, many farmers simply don’t have the time to learn the techniques and would rather consult with a professional. South Carolina’s Spence also runs a blog on Arduino projects. All of them, including content aggregator Reddit, are part of the rich online community that offers instructions, diagrams and troubleshooting tips for Arduino — rather than a dependency on commercial customer service departments.

“I have a big concern that tools will be costly and out of farmers’ control to fix them and tweak them to their needs,” Shute says. “It’s really important that that technology is done in a democratic way — that it’s not proprietary technology.” Some Farm Hack members have since taken Thiery’s schematics for Fido and modified them to suit their own requirements.

With an array of sensors collecting so much data, the question becomes what to do with it. For the last three years, Spence has saved all of the data about his pond and garden, but also general weather metrics like barometric pressure and rainfall. Sometimes he’s running over a dozen different sensors at once. The changes from season to season inform how he’ll plant the following year.

But an additional option is to share it online. Sometimes this is done playfully. Luke Iseman of San Francisco built “growerbot” a sensor set that monitors your garden’s health and tells friends how it’s doing, with Twitter-like status updates.

Sharing data from DIY sensors can also add real value to the overall farming community. This is the next level that websites like OpenWeatherMap.org and HabitatMap.org have taken on, dedicating themselves to aggregating that firehose of information so farmers – or anyone for that matter – can drill down to the weather patterns for their tiny corner of the world for future planting and harvesting.

If nearby farmers are collecting the same metrics and everyone shares that information to the digital cloud, “you could get a really accurate picture of microclimates that you can’t get from the weather service,” Spence says.

Farmers have always been a tinkering bunch, modifying tools and tractors to suit their needs. But now that empowerment has come to the circuitry that underpins those tools. Arduino is a relatively new technology but it’s quickly become clear that the sky’s the limit for how farmers can use the little microcontrollers to improve their livelihood.

“That’s the powerful thing about open hardware and open software,” Thiery says. “You have this thing that does 80 percent of what you want to do, you can search the Internet and find the stuff that does the last 20 percent.”