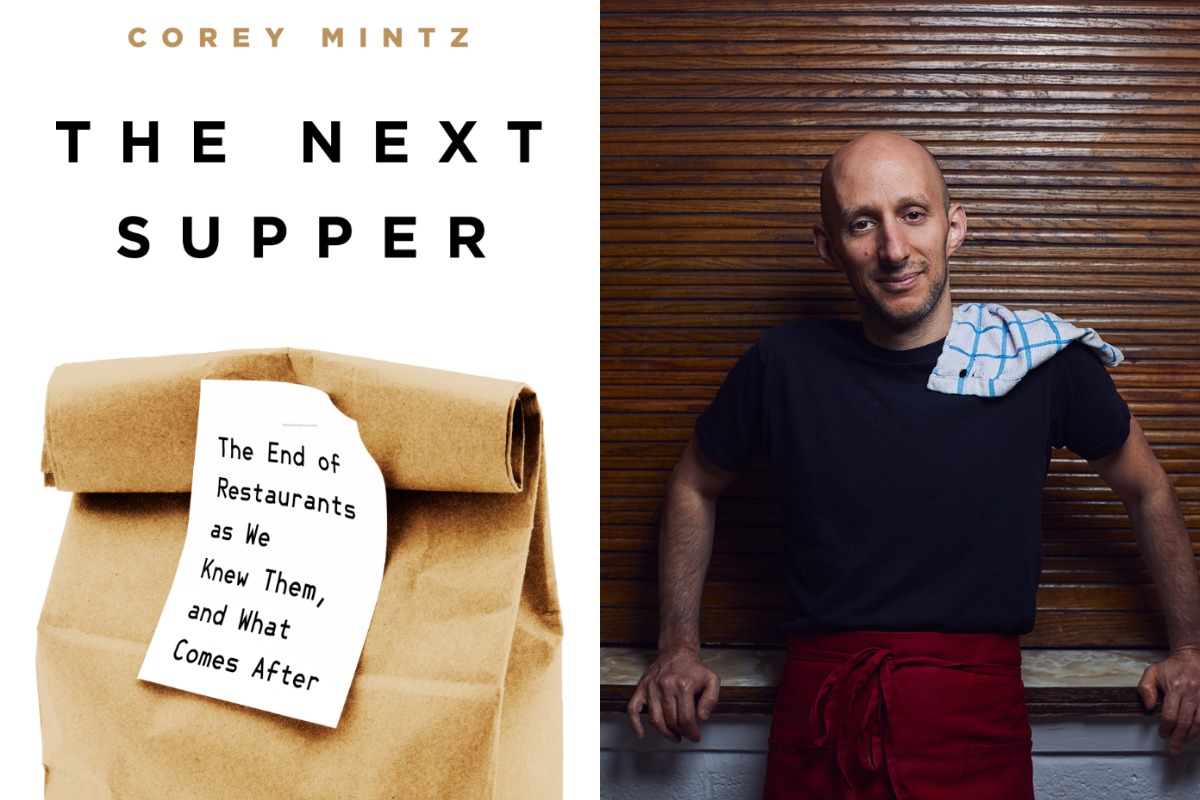

In his new book, Corey Mintz explores the end of the restaurant industry as we know it.

The restaurant industry has faced problems for decades. Wage theft and tip skimming are common complaints for front- and back-of-house staff. Aspiring kitchen staff will often have to work for free, in unpaid internships or “stages”, at the beginning of their careers. Although farm-to-table dining is trendy now, not every chef is so fastidious about sourcing ingredients, relying on underpaid farm labor. The issues go on and on.

While it’s true these issues have plagued restaurants for years, it’s also true that the pandemic exacerbated and magnified many of them. From navigating outdoor dining to adapting menus so dishes can travel well in takeaway containers, not to mention policing mask mandates to keep both staff and guests healthy, the ways that restaurants run has changed drastically in the last two years—that is, if a restaurant survived the pandemic at all.

But, as Corey Mintz points out in his new book, The Next Supper: The End of Restaurants as We Knew Them, and What Comes After, there’s a better future out there for restaurants, which are more than just places to eat and drink and socialize with your community. To get to that brighter future will require a little bit of work, says Mintz, both at an individual level and as a cultural shift.

As someone who has worked in the restaurant industry in all capacities, he’s uniquely positioned to tackle the topic. Mintz started his career in culinary school, then worked in restaurant kitchens and for catering companies before the drudgery of kitchen life took its toll. The long hours and the measly wages, combined with systemic restaurant issues such as casual sexism, lead him to pivot to a new career as a food writer. In the late 2000s, Mintz became a reviewer and restaurant critic before branching out to speak about the industry and culture of restaurants at large. Through his long-running “Fed” column in the Toronto Star, Mintz has hosted hundreds of people for dinner parties at his home. Politicians, artists, chefs, criminals and—according to his website—at least one monkey have all graced his table.

In the book, he delves into the array of issues restaurants are facing today—the very same issues that once drove him from the kitchen—and provides a few possible solutions. Mintz traces the recent history of restaurants, drops in some fascinating tid-bits (did you know that pizza was the first physical object sold online?) and helpfully gives advice on how we can rebuild the culture of restaurants from the ground up.

Delivery apps such as Grubhub and Uber Eats are some of the biggest issues restaurants face today. While they have magnified convenience for the consumer, they’re generally dismissed as a necessary evil by restaurant owners. Many dishes don’t taste the same after 30 minutes of travel, which degrades the product they provide. But, more importantly, delivery apps take huge fees from participating restaurants, while paying drivers subminimum wages. As Mintz details in the book, large restaurants are often able to negotiate better rates with the apps because of high demand for their products. While delivery apps often take a commission of 20 to 30 percent per order from restaurants, some major restaurant chains manage to negotiate a much lower rate—or no fee at all. “The apps need major brands, but don’t make any money from them,” Mintz writes. “So it’s the independents that pay the cost; your local ramen shop subsidizing a delivery service for McDonald’s.”

Despite the huge fees, restaurants keep using the delivery apps, because their competitors do. If they want to keep customers, they need to be available to them. “They are converting the customer into being delivery customers,” Mintz says. “They’re changing the nature by which people decide to go eat versus have food delivered, because they made it so convenient.” In the early days of COVID-19-related lockdowns, use of delivery apps more than doubled. Now, consumers expect that degree of convenience. So restaurants have to adapt.

Mintz also touches upon the ways in which consumers have become further disconnected from their food. At the beginning of the last century, he notes, close to half of the population was involved with agricultural work. By 2017, only 1.3 percent of Americans were involved in farming or ranching. Meanwhile, Mintz notes, a growing portion of household budgets goes to food prepared outside of the home.

Although diners might talk about the importance of farm-to-table dining or nose-to-tail preparations, that doesn’t mean they have any more knowledge of their food—or who picks it. In the book, Mintz describes a typical tomato farm in Florida. Tomatoes have to be picked while dry, so crews have to wait out the morning dew. But in order to get chosen for that day’s shift, willing workers have to show up around dawn just to wait. That time is unpaid, of course. Instead, workers get paid by each bucket of tomatoes they pick. A bucket weighs about 32 pounds; Mintz notes the average pay per bucket is about 45 cents.

“At every stage in our food system, there’s tension between what food actually costs to make, and what people are willing to pay for it,” Mintz writes. He goes on to say that when a meal is cheap, “it costs us somewhere else,” such as with our health, at the exploitation of workers or the environment or both.

But not all hope is lost, says Mintz, who ends each of the book’s chapters with tips and concrete actions that everyone can take. For instance, tip your delivery drivers in cash or find restaurants that use their own delivery service. Find out from where your favorite place sources its ingredients. If you feel disconnected from your food, Mintz suggests a quick step to change your world view. On your search engine, type in the name of your state and the words “farm worker” or “justice” or “advocacy” or any similar terms. “You’ll find, inevitably, a grassroots group that is advocating for change within the local farming industry,” says Mintz. Start following those groups on social media and stay up-to-date on their causes. Having that exposure to local farming groups will make you a better-informed consumer. “Just invite those people and the work they’re doing into your social media feed.”

The tips aren’t just platitudes either, a balm at the end of each reality-check chapter. Mintz does believe that there is a real social will to change things for restaurants and restaurant workers now. While the pandemic exacerbated many issues, it also made conditions ripe for revolution. Ongoing staffing shortages have allowed restaurant staff and servers to demand better hours, better wages and more respect for a job deemed “essential” by the government.

“When they were furloughed [during the early coronavirus pandemic, so many people] had time on their hands for the first moment in a decade for many of them. Some of them were not shy about voicing their opinions about things that they always considered unfair, but previously, were afraid of losing their job. And now they were like, ‘what job do I have to lose?’” Mintz says. “There’s an opportunity for people to work together to advocate for bigger changes within their workplaces and within the industry.”

As many places transition out of the worst of the pandemic, Mintz is hopeful that more of the problems he addresses in The Next Supper might finally get resolved.