In his new book, Luke Manget shows just how integral ginseng was—and still is—to the Appalachian experience.

There was a time, not too long ago, when ginseng studded the forest floor. From Alabama up to the foothills of New York and further west, pointed leaves with jagged edges and small, bead-like red berries popped out of the rugged hillsides. Native Americans used the root as a stimulant and to treat headaches, fever, indigestion and infertility. Wild ginseng was similarly prized throughout Appalachia as an aid for digestion and for giving users a boost of energy. It’s even been promoted as a sexual aid, used to treat erectile dysfunction. And for a time, it became the backbone of the Appalachian economy.

But after decades of over-foraging and mass extraction, wild ginseng is no longer plentiful. These days, going to dig ginseng, or “sang,” is less of a pastime and more of a hunt, with locals hiding their favorite secret spots to preserve what’s left of the plant.

As Luke Manget writes in his new book, Ginseng Diggers, the history of ginseng is not simply a story of plant cultivation or resource management. The history of ginseng in America, and in Appalachian states specifically, is also the story of “the transition to capitalism…the root and herb trade serves as a reminder that the specific impacts of the region’s capitalist incorporation depended on the ecology of a particular commodity’s production.” In other words, the popularity of ginseng pushed Appalachian communities further out of subsistence farming and into wage-earning roles.

It’s a lot to put on a little plant, but Manget did plenty of research, although it was not always as easy as it might seem for such a prominent plant. “You’re looking at sources that nobody’s looked at before,” he says. “You’re piecing together a research landscape that didn’t exist before.”

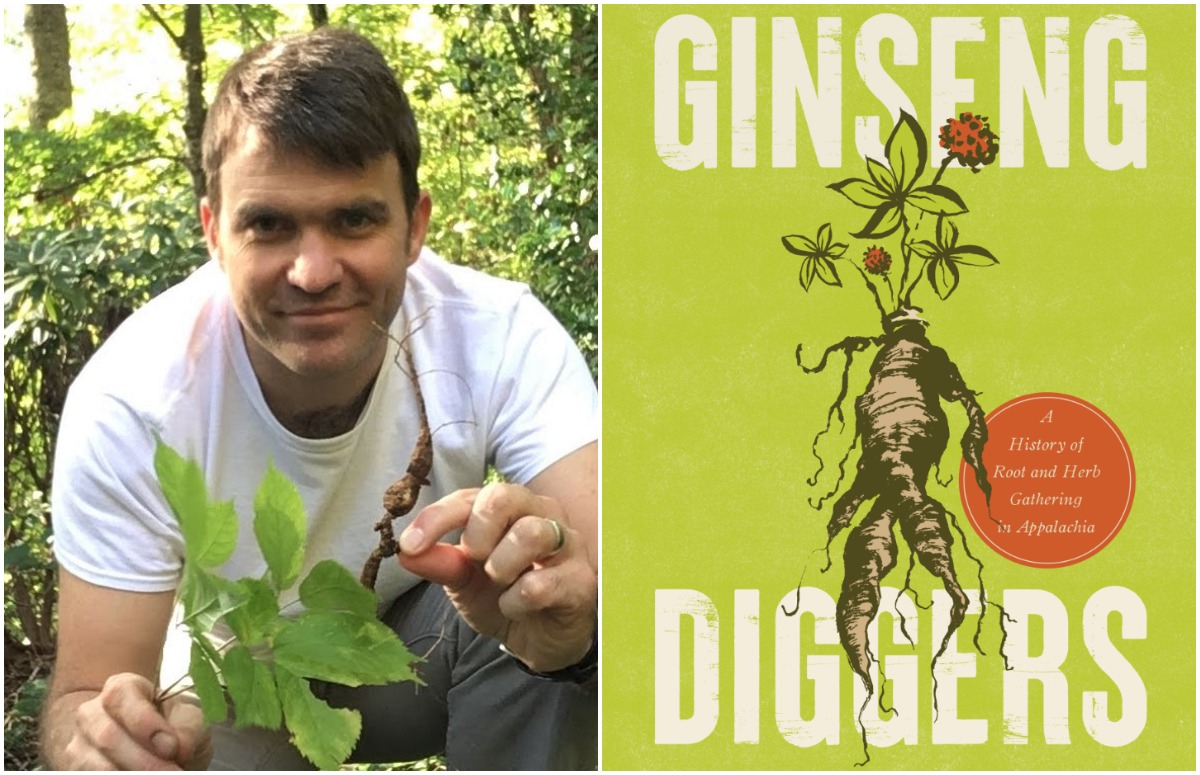

Luke Manget, author of Ginseng Diggers, holds a wild ginseng root. Photo courtesy of publisher.

He looks back to the 1700s, when American ginseng was first found to be purchased in a global market, expanding from there. While Manget pours his research skills into the book (he is a history professor at Dalton State College in Georgia, after all), his first connection to ginseng is a familial one. Growing up in Kentucky, Manget listened at his grandmother’s knee as she talked about digging for wild ginseng. “Being able to put those experiences into a broader context, and realizing that those activities were a significant part of Appalachian history…it helps contextualize my family history a bit more,” Manget says.

Manget’s own family history is similar to many who grew up through much of Appalachia, where ginseng played an important role in the economy. In many ways, it even functioned as a social safety net, sustaining the local community. “If you had a bad harvest, you could always make money [digging ginseng],” Manget explains.

[RELATED: Getting to the Root of Ginseng Farming’s Impact on Native Plant Populations]

Of course, things have shifted. Ginseng always had local value as a medicinal root. But once American ginseng was introduced to Asian markets in the 1750s, its popularity skyrocketed. Even pioneer Daniel Boone got into the ginseng trade. This prompted intense interest in harvesting wild ginseng, giving way to micro-gold rushes across the region. “Minnesota had a really interesting boom, around 1859. People went there specifically to dig ginseng, and it lasted just a few years before it was pretty much dug out, and declined to the classic boom and bust cycle,” Manget says.

Further south, throughout Kentucky, Virginia and North Carolina, the extraction period for ginseng peaked a little later, when people flocked to the area after the Civil War. Amid widespread economic devastation in the South, people rushed to the hills to find their fortune in ginseng. “The locals who had been used to stewarding patches of ginseng in the woods now couldn’t do that,” says Manget. “They were forced to become more short-sighted and dig up what they could, because they couldn’t rely on it to be there.” North Carolina and Georgia became the first states to try and staunch the mass extraction of ginseng by instituting a ginseng season, with harvesting forbidden outside of the mandated times. Other states soon followed suit, although it’s debatable how effective such mandates were on a larger scale.

According to Manget, it’s difficult to estimate how much money was made from ginseng in a few short decades, but it certainly had an impact on the regional and national economies. In an 1872 report that Manget writes about, Cherokee County in North Carolina produced around 80,000 pounds of ginseng, with each pound selling for about 26 cents, which is about $6 in today’s market, totalling around $480,000 for the season in current dollar amounts. And that was just one county.

Wild American ginseng plants. Photo by Christopher Baldridge, Shutterstock.

It is this fervor for wild ginseng that nearly killed the plant entirely. What was once an abundant root was ripped out of the ground in bushels. Because ginseng has a decade-long growth period, it isn’t easily replaced.

Today, most ginseng is cultivated, with Wisconsin a primary producer of the plant. Although there are still spots where wild ginseng grows, such as Pennsylvania and Tennessee, most diggers are secretive about their hunting grounds. Manget understands the compulsion. While ginseng can be cultivated, it needs a lot of shade, as well as a specific soil density. Cultivation never took off at the same scale, which Manget says is partly because there was a shift in thinking of this free-growing plant as being private property. “People were used to hunting for it, and it was difficult to convince everyone that someone has exclusive rights to it,” Manget says. “That concept was difficult to enforce in some of these mountain communities.”

Plus, many people simply prefer the hunt. Spotting those pops of red berries bursting through the green forest floor is a rush. It’s a sport that never fully died; it’s simply lying low, living on in the Appalachian foothills.

Very interesting! Thank you.