In a new book, former FDA employee Richard Williams offers an indictment of the agency, urging it to focus on food safety challenges in more impactful ways.

How much do you really know about the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)? Not enough, Richard Williams would bet.

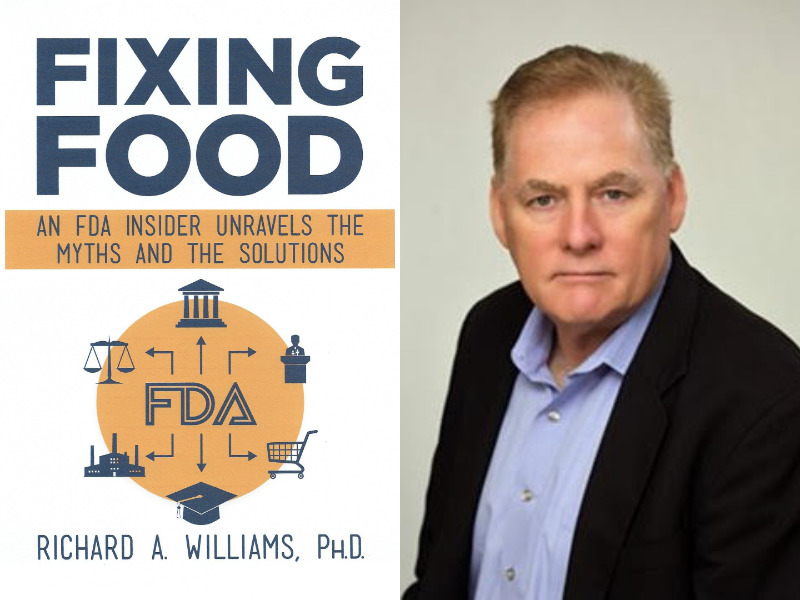

An economist by training, Williams served as the Director of Social Science at the agency’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition for 27 years. He chronicles that time in his new book, Fixing Food, in which he suggests the FDA may not be the protective force that many Americans believe it to be. According to its mission, the FDA “is responsible for protecting the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices; and by ensuring the safety of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation.” Instead, Williams presents the organization as a bloated bureaucracy, one that does try to keep food and drugs safe for the public but works at a snail’s pace, often focusing on minute details rather than the bigger picture.

In Fixing Food, he traces the years he spent working for the FDA, from 1980 until 2007. Time and time again, he clashed with others at the organization. Williams says he loved the idea of working on something as important as food safety, but he quickly realized that looking busy was often more important than coming to a resolution.

“When I was working on my very first regulation, I said ‘I don’t understand why we’re doing this. This doesn’t seem to be helping anything,’” Williams recalls. “And [my boss] said, ‘It doesn’t matter whether we accomplish anything. It only matters whether or not we appear to be doing something about a problem.’”

It was this ethos—to look busy—that Williams says the organization, and by extension many of its workers, was often concerned with over the years. The focus on the FDA’s appearance was one of its main impediments to actually making food safer, according to Williams. “We’re not solving the problems of food safety,” he says. “Every year the FDA applies for a new budget, usually higher. And they say ‘one out of six people is getting food poisoning.’ But they say that every year, and they’ve been saying that for well over a decade.”

When it comes to things such as inspections of food plants, Williams says the FDA can also be quite hands-off. They happen far less frequently than you might expect, he says—about once every six years. Instead, individual state agencies are responsible for the bulk of government inspections.

Photos courtesy of the publisher.

Other initiatives, such as food labels, receive a lot of attention and investment and yet still miss the larger point. For instance, the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was a sweeping piece of legislation that required food labels to use common names for ingredients, and it could hold manufacturers accountable for misrepresenting their products. But it has also allowed the FDA to zero in on small producers. Williams recalls a manufacturer in New England who listed “love” as an ingredient in its product, and the FDA sent him a cease and desist letter. Today, the act can cause long delays within the FDA as they address correct labelling, such as in the case of almond milk.

“They’re spending over two years to decide whether or not almond milk should be allowed to be called almond milk,” says Williams. Because, you know, almonds don’t lactate. But also because the FDA and Congress both face lobbying from the dairy industry, which opposes the use of the term “milk” for plant-based products, which it claims are not nutritionally similar to animal milk. For the FDA, it’s an issue worth exploring deeply, spending time and money to investigate the term “milk” and appropriate definitions. For Williams, it’s a waste of resources that could go to nutrition and food safety, rather than deciding how industries could be shielded from competition.

Tinkering with food labels is like “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic,” says Williams, not only because he argues that the FDA is focused on the wrong details but also because he says the evidence shows that many food labels aren’t all that beneficial to regular consumers.

“Here’s what has to happen: Consumers have to actually look at the labels, particularly the nutrition facts panel, they have to read them, they have to understand them, then they have to make better choices, healthier choices as a result of what they’re reading on the labels,” Williams explains. “I modeled it out; I thought it would happen based on the information that I had at the time. And I was just wrong. It just didn’t happen. And what we came to find out later on… [is] that consumers don’t understand food labels.”

Williams points to labels on products with claims such as “natural” or “eco-friendly.” The label creates a halo effect, where the consumer will have a higher level of trust in the product, regardless of the actual nutritional facts. In order for the FDA’s focus on food labels to have an impact, Williams argues that the entire consumer education around food labelling needs to be improved.

So how do we actually fix food? And how does the FDA fit into that mission? Williams suggests two options in his book. The first suggestion is that consumers put more pressure on Congress to revisit and update older laws, such as the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

The second idea he floats is taking some of the individual pressure off of the FDA and making the organization a super regulator. “We would have private agencies that specialize in looking at new innovations at a much more granular level than what we’re doing right now. And the FDA regulates them. That way, we could balance how much time it takes and how much money it takes to get through the process, with making sure [the products] don’t present significant risk to consumers.”

While Williams says he often disagreed with others throughout the decade he worked at the FDA, he stayed because he was fascinated by the work. He hopes that readers are similarly fascinated by this peek behind the curtains of one of the country’s most influential administrations.